directed by Marcel Camus

screenplay by Jacques Viot

inspired by the play Orfeu da Conceição by Vinicius de Moraes (1954)

adaptation and dialogue by Jacques Viot and Marcel Camus

Criterion #48: Black Orpheus. In Portuguese, shot in Brazil, directed and produced by Frenchmen and considered a French film.

If you don’t know what this is, you can go to the Criterion site and press play to watch the preview. It gives a good sense.

I think the aspect of “blogging” that is most artificial to me — and accordingly the least fluid element of my writing — is form. Thoughts are not the same thing as a cohesive essay. In grooming the former to pass as the latter (like Henry Higgins), I feel that I am wasting my time and mental energy on fakery. Fakery ought not to be any part of this. If I wrote in drafts, on a second pass I would no doubt be inspired to impose some form of my own invention, but I really want to do these in one shot. That’s the nature of the exercise. And in one shot I’m not going to be thinking formally, because, as I said, thinking isn’t inherently formal. Mine isn’t, anyway.

Furthermore I’m a bit skeptical about the ideal of the “cohesive whole”; I think it’s overemphasized generally. I’m going to make an effort to remain more authentic to my inner parataxis. (Yeah that’s right, parataxis.)

I make and fail this pledge pretty regularly.

On occasion here I have criticized works of art for not living up to an idealistic standard: that they should aim to be of spiritual/emotional/psychological benefit to their audience. This movie decidedly meets the standard. It is joyous and vibrant and celebrates life as being full of color and feeling.

Everything else about it is secondary. The mythological scheme that’s supposed to impart epic significance is actually completely gratuitous. Color and light and music already impart all the epic significance needed; that’s how movies work. (Color and light and music plus the freedom to stare at people’s faces with impunity.) In fact, in every respect other than vibrancy, this movie is pretty flimsy stuff. But that’s no criticism at all.

Actually, for me the value of the Greek overlay flowed the other way; the ecstatic immediacy of the movie’s fabric of music and dance and festivity gave me a new sense of what myth is.

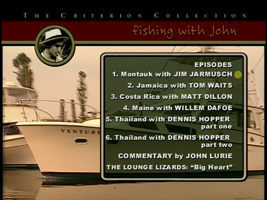

Recently watching Fishing With John and a while ago watching Shock Corridor, I thought about the distinction between private home movies and creative work for public consumption, because in both of those cases that distinction was partially erased, to unusual effect. The spirit of Black Orpheus is also closely related to the spirit of private vacation footage, but in the more familiar mode of travelogue: here are some of the stimulating sights and sounds of X locale.

Perhaps it seems that what mainly distinguishes something like To Catch a Thief from your grandparents’ home movies of their trip to Europe is budget and camera skill, or degree of fiction. But what really makes the difference, I think, is the outlook that governs the photography (and is thus embedded in the film). The thing about To Catch a Thief‘s traveloguing that makes it unlike home movies is not the fiction per se but the fact that its camera’s-eye-view of the Riveria is commercially calculated and thus impersonal. Whereas any home movie is through-and-through an expression of its maker’s particular spontaneous sense of the world.

And this sense of the world is not diametrically opposite to fiction; on the contrary, many people — me and John Lurie included — have, in the act of capturing a stimulating “real” travel experience, been aware that their spirit of present wonder is already closely proximate to fantasy and figured “why not add some fiction to this?” Make-believe seems to have an organic place within that kind of joy-in-where-you-are.

All home movies are already a kind of make-believe, a nourishing kind based in the deep interpenetration of the imagination into one’s happiness. (It sounds like I am doing an impression of Gaston Bachelard, but it just came out that way.)

In fact you could say that vacations, even before you film them, are already a form of narrative fantasy. (Come to think of it I think that was the subject of a pretty good literature lecture I heard in college.) The use of a camera is in this sense just a way of giving perceptible form to the imaginative world in which one is already living. Which sounds to me like a definition of the function of art. So I see this overlap of the private/documentary and public/drama impulses as basically good and healthy.

Black Orpheus is overtly rooted in the joyful self-mythologizing impulse of the tourist, but it also encompasses classical myth. And then within its fictionalized travelogue of Rio’s Carnival (itself already a ritual of fantasy) it includes footage of an apparently real Umbanda ceremony, which, intercut with the actors, is made to serve as part of the fictional mythological story. This stew of reality and fiction was touching and stimulating; it revealed to me that religion, superstition, narrative, myth, exoticism, tourism, and self-image are all part of the same lump of imaginative feeling. And that this lump is none other than the same source that gives meaning to dance and music, a well of feeling with which we are all intimately familiar. (If Bachelard had written a book on travel I imagine he would have expressed this, but better.)

In the Disney conversation about Saludos Amigos, I said — yes that’s right, the authorial voice of these solo entries is the same BROOM who participated in the Disney discussions! — that I was pleased by the idea that a frothy travelogue could serve a propagandist political function. I find the very notion of the government adopting a Good Neighbor Policy heartwarming and politically attractive. It is the most honorable possible mode of leverage for the political manipulation of the public, and a grossly underused one: trying to make people happy about things that it would benefit their government (and the world at large) for them to be happy about.

All such policy is now of course utterly utterly defunct. I suppose presidential campaigns do a little of that sort of propaganda of positivity, but with such transparent ulterior motives and on such a petty scale that in the long term it only increases public cynicism. I’m talking about long-term subtle propaganda campaigns to get Americans to, say, think of the middle east as a fabled land of natural wonders and cultural glories. And of course vice versa, to send Pato Donald over there with a few benign skits to introduce our Iranian friends to the mystique of the Grand Canyon and the Space Needle, or whatever. It’s a piece of the international cultural landscape that is painfully lacking.

Probably Disney (for one) has been approached with this sort of proposal in the last 50 years but said “no way,” because the risk of being seen as government pawns, or even just meddling in foreign policy on their own dime, is far too toxic for the shareholders in this day and age. Understandable.

I bring up politics at all only reluctantly. This film could be taken as a Good Neighborly fantasy (not that the French filmmakers are exactly neighbors to Brazil, but we’re all planetary neighbors, right?), or it could remain just a human fantasy, which is all that is actually captured on the film, and is what a good vacation is. (At least in my mind. Politics are abstractions but the blue of the sky and the good warm air are not.)

But. I bring this up because the DVD (and apparently the discourse at large about this movie) is full of another way of “politicizing” it, which really irks me. Basically the gist is: this is a movie set in the favelas, the slums of Rio, which are in reality no bossa nova love poem but a vast nightmare of poverty and crime and hopelessness. If you saw City of God you can understand that the lyrical vacation fantasy of this movie is to say the least highly inaccurate, even for 1959. The critique writes itself, right? Naturally, this movie is irresponsible, offensive, whitewashes a serious issue, tells unconscionable and condescending lies about Brazil and blackness for the amusement of foreigners, blah blah blah. It is a Song of the South of Rio. (My summary of the criticism; nobody actually says that in so many words.)

Now, to be clear, everyone on the disc who brings up this point of view then dismisses it. The film, they essentially say, is an outsider’s exoticist distortion of Brazil, but a forgivable one, especially in light of what it did to promote real Brazilian music (see below). But I say that even in entertaining the criticism in the first place, we hurt ourselves. This film does not require forgiveness. The impression given by the people in the documentaries and such — essentially all of whom like the movie! — is that liking the movie may be a kind of error, but they have made peace with the error. That makes me mad. Either it’s an error or it’s not, and if it’s not an error, why are you all talking about it?

The critique is senseless to begin with. It is based on a guilt that has no political source and no political end. Of course this movie is a lyrical fantasy. It could not be more explicit about it. That it derives from a tourist’s exoticist raptures does not actually complicate that; all fantasy is exoticism and all rapture is irrational and inexact. Being angry about this is like being angry that back in Nagasaki the fellers do not chew tobaccy and the women do not wicky-wacky woo, because that was always racist and inaccurate and furthermore the fellers and women were all later incinerated and the song is thus in poor taste. The bonus features here keep returning to the angle that “well, yes, but the song remains catchy nonetheless.” There is no nonetheless. The bomb has no bearing on the catchiness, period.

The most hateful thing that politicization does is deny that there is any such thing as politicization. “Everything is already inherently political; it’s for us to come to terms with that.” This is vile sophistry. Nothing is inherently anything. The power to choose one’s perspective is equally the responsibility of those who choose the perspective of pooping at parties.

This perspective requires vigorous defense instead of the implicit free pass it is constantly given, because despite its obvious good intentions, it is truly unclear what good it actually does, whereas it is very clear what ill it does: it puts everyone on a defensive footing about everything. And then that gets put in the bonus materials on my DVDs and brings me down from a state of general dreamy transport into a state of rationalization and qualification.

Here’s my defense of my position: I believe that people naturally do good to one another when they have 1) freedom to choose their actions and 2) a feeling of unthreatened well-being. The scolding guilt of moral obligation can only diminish both of these prerequisites. Going to a happy party makes people more likely to do good afterward; being told “enjoy your party but just don’t forget to keep in mind that you are always, passively or indirectly, the cause of suffering in others, and that the greater your pleasure, the more shameful your sin” only makes that less likely to happen. Plus it’s blatantly untrue. Suffering that occurs simultaneously with pleasure is not caused by it. The starving people in China very truly do not care whether you finish your broccoli. Morality is paratactic, not hypotactic. You heard me! Take that!

After reading this you might ask, “Well, what about Song of the South then? Are you really okay with that?” To which I say, testily, “I don’t understand the question.” Am I okay with the movie having been made? Sure. Am I okay with people being so offended by it that they wanted it taken out of circulation? Sure. Am I okay with the distributor complying? Sure. But: am I also okay with people not being offended by it? Yes. I am okay with myself not being offended by it. If it weren’t so boring I might even enjoy it. (Song of the South, that is. Black Orpheus I did enjoy.)

What I am not okay with is people being not okay with me not being offended by it. I don’t think their claim that such censure serves a philanthropic purpose holds any water. This is the thrust of my argument.

However, my being “not okay” with censorious zeal is only another spiritual hurdle for me to go over (or is it under?). The more okay with such people I can be, the better my life will feel. I’m in the process of inching under.

In brief: Intolerance of error is not equivalent to, nor nearly as valuable as, love of truth. The former is frequently counterproductive, the latter never.

This movie was made with real love of a form of truth. Any “errors” bob harmlessly in the wake of that forward impulse.

Furthermore I declare that: Marcel Camus is neither the same person as, nor any documented relation to, Albert Camus.

Boy, I really didn’t say much about Orfeu negro but it just worked out that way. I’m allowed.

It’s pretty like a postcard. Haven’t you ever wanted to live and love in a postcard? Well, I have.

It’s actually remarkably like a live-action version of one of the Disney good neighbor movies. Which is the sequence where the buildings all dance along? (I think it’s “Os Quindins de Yayá”.) That spirit is exactly captured in the opening scenes here.

It also goes on a bit. As a kid I would have found it terrifically dull and disingenuous. I would have felt that I was being pandered to with supposed “beautiful people” and their supposed “beautiful story,” just another bout of flaccid cultural fawning, all endless dance sequences and no real bones to it. But I am old and mellow enough now to know that not all dullness is an error and not all faux-naivete is hypocritical or pandering. The goodwill and good color carried me happily through.

Hey, don’t blame me, I’m just a guitar.

I had intended to link to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s infamous Carnival in Rio video somewhere in this entry as a joke, but I just watched the clip (for the first time in years) and it made me feel so uncomfortable that I can’t in good conscience impose that on you.

The music is the glory of the movie. The best bonus feature is two guys who know what they’re talking about explaining what bossa nova is and isn’t, where things stood when this movie came out, and tracing Jobim and Gilberto’s path through this movie’s soundtrack and beyond. I wish that feature had been longer. The worst bonus feature is a full-length French documentary where they go to Rio “in search of” the movie today, with nothing particular to say and a lot of boring footage to say it in, cut together very badly. I’ll admit that as I type this I still haven’t watched the last 20 minutes of it, but I promise will before I click “publish”!

Anyway, the music is almost constant in one form or another, and is overtly the soul of what the movie has to offer. The atmosphere of the middle section of the movie almost exactly the same as that of bossa nova: i.e. waking in a warm breezy beach house. There is also some genial raucousness for scenes of the eager crowds, and of course a couple of more intimate mellow-voiced love songs. It’s all buoyant and evocative; it’s no surprise that the soundtrack was a big seller and sparked the bossa nova craze.

There is a main title song (Jobim’s “A felicidade”) but there are sound effects all over it. Then in the middle there’s “Manhã de Carnaval” by Luis Bonfá, which is generally thought of as the breakout hit from the score and accordingly gets called simply “Black Orpheus” on a lot of jazz albums. But if you’ve seen the movie you’ll probably agree that the selection has to be the wonderful finale, the “Samba de Orfeu,” also by Bonfá. The ecstatic poignancy of the ending, with the children’s voices, has been widely imitated and for good reason. It’s not quite the same without the visual but it’s still very charming. Track 48.

Okay, I watched the rest of that pointless documentary. If I’d been the Criterion producer I would have tried to extract only the brief bits of interviews with the original cast and crew, which are probably no more than 10 minutes. Seeing the guy who played Orfeu in 2005, bald and overweight but still with a great smile, is obviously a desirable bonus feature. (He has since died.) I wonder if they tried to do that and the filmmakers said “we will only give you permission to include the film intact.” Because as a whole it’s really not up to snuff, certainly not up to 88 minutes of snuff.