1999/2004:  2010 Blu-ray:

2010 Blu-ray:

directed by Stanley Donen

screenplay by Peter Stone

story by Peter Stone and Marc Behm

Criterion #57.

I wish I loved it. I do like it quite warmly. It’s a cheery, imperfect movie.

Here are movie stars. Movie stars are people so splendid that they can watch their own movies as they’re happening. Like us. Life is a movie and we fall in love while we’re watching ourselves in it. This is the essence of romance and feels very true. Romance is to be together in the dark while a movie starring you is going on.

The meaning of this movie, it seems to me, is in that scene, in the lines: “Do you realize you’ve had three names in the past two days? I don’t even know who I’m talking to anymore.” / “Well, the man’s the same even if the name isn’t.” Key to this exchange is that neither party is distressed; to the contrary, they are Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn on the boat in Charade, at the very pinnacle of ease and romance. The message is: who’s to say what it means to care, or not care, about the intricacies of this particular bauble of a plot, these particular identities… or, for that matter, identity in general? It doesn’t change the underlying ineffable reality of whatever it is that’s happening for “Regina” and “Brian,” or for Cary and Audrey, or for us watching, or even, perhaps, for the late Mr. Leach and the late Ms. Ruston. What is it that’s happening for them? Life, happiness, the unknown. Maybe a mystery story. Something.

Like I just said about Hitchcock in the previous entry: all film is essentially surreal. And since we recognize ourselves in film, perhaps all life is surreal too.

It’s nice for this to have come right on the tail of The 39 Steps. This is exactly the same charade, but with that extra layer of self-awareness added: where Robert Donat never tipped his hand more than to smile with preternatural aplomb, Audrey and Cary stop after nearly every scene to savor their pleasure at being alive and a part of this game. Charade is happy to be a movie, and is happy that we are happy that it is a movie. For all his playfulness, Hitchcock held to a kind of British propriety in not letting his characters openly admit, within the frame, that none of it mattered, that all of the intrigues were simply a form of joy. (But he finally, finally, eventually, got there, in the very last second of the very last thing he made.)

On the other hand, sometimes this movie feels like a thriller starring a tulip in a vase. (I don’t mean in a Magritte sense, though that does sound interesting. I just mean professional tulip Audrey Hepburn and Miss Hepburn’s Clothes By Givenchy.) At one point we cut to Audrey alone in her room, momentarily to hear Cary Grant at the door. She is lying on her bed perfectly poised with her pointy arms behind her head, in acutely stylish clothing, placidly staring. I’m not saying I object to watching this; nobody would object to watching this. I’m just saying it’s often not at all like watching a mystery, or a comedy for that matter. It’s like watching a tulip in a vase. Very pleasant!

The tulip meets a mahogany humidor. After an hour of mostly thrills and goofs, she quite seriously says “I think I love you” to Cary Grant. This is the moment in movies when my defenses usually snap up: “Seriously??” (Yes, I know, whatever that says about me. But whatever it says about me, I’m not alone in it.) But here it was okay. It was right that she loved him. The one thing we really believe about Audrey and Archie — or at least their avatars — is that they are both committed to this pleasurable bantering distance from any real troubles — not just as a performance of cool, but as a mode of encountering life. In each other, within the script, they find a fellow traveler through the cinematic darkness. So of course they love each other.

On movie terms, that feels like a very real kind of love. Such love doesn’t necessarily have to take the form of kissing, or getting married at the end, or really anything in particular. They seem to know that too. They don’t need anything from each other. That’s why I believed it.

More concrete link to the previous movie: the housekeeper finds a dead body, screams directly into the camera. Link to the movie prior to that: Audrey Hepburn and Juliette Binoche are very closely related types. Link to the movie prior to that: Hm. I guess that Walter Matthau was in JFK with Kevin Bacon and Kevin Bacon was in Apollo 13 with Apollo 13. Link to North By Northwest: all of it, obviously, plus Cary Grant talks to someone from the opposite end of the same bank of telephones. Link to To Catch a Thief: really, truly, all of it. And I note the inclusion of Princess Grace Commemorative stamps when the stamp dealer inventories the cheap packet he gave the boy. Seems intentional.

Did Hitchcock like Charade? Was he flattered or annoyed or indifferent or what? What did he have to say about it? Why isn’t this easy to find out?

My quibble with the movie is essentially that it is loose sometimes when it wants to be tight and vice versa. But that’s the price of charm; if you want to catch it in a bottle, the bottle needs to be various different sizes. Or a vase. The whole thing plays much better on second viewing, when it no longer has to work.

Also, the last act is rhythmically stronger than the rest, which is helpful to the overall impression — thanks to a considerable assist from Henry Mancini, who hits all the necessary nails squarely on the head for 15 minutes straight.

Here’s the main title, which accompanies the great Maurice Binder animated titles. I love credit sequences like these, not just because I love abstract animation anyway, which I do, but because I love the idea that this world of abstract imagery somehow is the movie, is somehow an approved translation into dream-terms of the very DNA of the live-action movie that follows. The idea that a movie can have a subconscious, and that it is right to begin inside it. I enjoyed many things in Charade but the single moment that most excited me may have been when those arrows first snaked onto the screen at the very beginning, to the sound of pure percussion pattern. This is a story, it says, but first and foremost it is a pattern. Cool. That already makes me feel good. Can’t you feel your “cares” begin to drop away with the recognition that underneath all the things of man and Hollywood are these arrows and colors and stripes and a steady beat?

One other thing about these credits. Charade, notoriously, happens to be in the public domain, and thus legal to distribute freely. How did this top-class studio release fall through that particular crack? This is how. Look close. The copyright notice lacks the word “copyright” or the (c) symbol. Even though it’s very clearly, obviously, intended as a copyright notice. Even though it announces the date of publication, explicitly reserves all rights and specifies their owner. Can you believe the law is really so vindictive as to immediately place this film in the public domain upon its first commercial exhibition with this faulty notice? Well, it’s not any more, but it used to be.

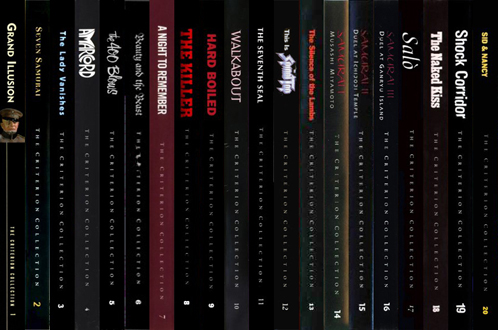

So thanks a lot, Maurice Binder and/or unidentified Universal employee(s), and thanks a lot, U.S. law prior to 1978. Anyway, be warned: don’t pay for any release of this movie other than the official Criterion edition. Don’t watch one for free, either, if you can help it; the quality is always much worse than it needs to be (this goes for the Netflix streaming version, too), whereas the Criterion Blu-ray looks great. To its credit, Criterion makes no mention at all of the public domain issue and simply treats the film as though it were fully owned by Universal, which is after all the only decent thing to do.

The commentary track by Stanley Donen and Peter Stone is very good. Charming, personable. The same warm good cheer of the movie can clearly be heard in their two personalities. Donen seems to genuinely believe that some listeners might never have seen the movie before, and is intent on not spoiling surprises for first-time viewers. Stone thinks this is absurd but plays along.

During the swinging revelry of the orange-passing game, the two reminisce that they shot this during the Cuban Missile Crisis and that everyone felt that they were doing something incredibly frivolous and pointless given that the world was about to end. To me, this knowledge only deepens the romance of the scene, and in fact of the whole movie.

The woman who does a take when George Kennedy is holding Cary Grant at gunpoint and tells her to wait for the next elevator is clearly a non-actor but still does a pretty funny take. It’s both amateurish and effective; I watched it several times. I often think “if I had to do this bit part, could I do it?” Probably not as well as she does.

2012:

2012:

(out of print by 6/01)

(out of print by 6/01)

2009:

2009:

2007:

2007:

2007:

2007: