2001:

directed by Sergei Eisenstein

with the collaboration of Dimitri Vasilyev

screenplay by Sergei Eisenstein and Pyotr Pavlenko

[Aleksandr Nevskiy] = Alexander Nevsky, Criterion #87.

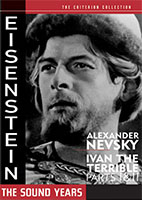

= disc 1 of 3 in Criterion #86, “Eisenstein: The Sound Years.”

(Sorry, guys: no trailer available.)

Like many people, I had known this title principally for its music. Now I’ve seen it. Too bad about the movie.

I found Alexander Nevsky unengaging in the extreme; I’m a fairly limber cultural masochist and this still managed to befuddle me. I procrastinated the DVD all the way to the library’s 10-renewal limit. That’s happened only once before, with The Last Temptation of Christ. Not a coincidence, I think. Both films have the same underlying flaw: they’re essentially dutiful, made to placate a threatening authority rather than achieve anything in itself. They feel like homework. Scorsese’s threatening authority was the Catholic church in his psyche; Eisenstein’s was Stalin. In both cases the artist set aside his authentic enthusiasms to make a show of eating his vegetables. There’s nothing worse.

Unlike Scorsese, Eisenstein didn’t fall into this trap for psychological reasons; he was pushed in. He did it because the alternative was to be shot. I can’t blame him. But there are heaps of Soviet propaganda that nobody watches today, exactly because it was all produced in bad faith under duress and is accordingly unrewarding. This movie survives in film studies and in the Criterion Collection because Eisenstein’s craftsmanship purportedly elevates it above the heap. But craft is in service of art. If the art is manifestly void, what can the craft really be worth?

My beef here is not political. Propaganda can be legitimate art, and I’m not inclined to hold ideological grudges against movies while I’m watching them. If this had been aesthetically digestible I would have eaten it up regardless of the politics. The problem is that it’s not good propaganda. It doesn’t have any heart in it, just mind. And propaganda has to be all heart; that’s the point. Xenophobia is supposed to be a thrilling adventure! If you’re making a shameless appeal to fear, pride, and anger, and it comes out stolid and monotonous, something’s gone very wrong.

The fact that Eisenstein made it this way and then the Stalinists applauded it this way proves that the whole Soviet ideological operation was a merry-go-round of insincerity. Everyone involved was surely perfectly capable of noticing that this movie contains no actual characters or emotions. Or they would have been, if they hadn’t been so committed to self-delusion. It’s hard to believe anyone has ever been truly patriotically stirred by Alexander Nevsky; it’s more like a billboard than a movie. I guess the Soviets were pretty into billboards, too.

Yes, I know, the movie was terrifically popular in its time. I believe those audiences went to see images and hear sounds. There are several good ones here. I just don’t believe that they were feeling the patriotic feelings that are the whole point of the project. Or rather I don’t believe that this movie drew out those feelings. It might have given people a convenient excuse to indulge feelings that already existed. Not well-adjusted feelings of simple patriotism, mind you! Something more akin to Frank Sinatra’s immortal “I just wish someone would try to hurt you so I could kill them for you.” If you were already champing at the bit for some enemies, there are indeed pictures of some enemies in this movie. Good enough for government work!

Even from this limp film, one can tell that Sergei Eisenstein (file photo) had a genuine talent, but a formal one rather than a fluid one. His conception of cinema seems to have been something like a photo gallery, or a comic book: a series of framed images, each one attempting an iconic quality. That’s all well and good on paper, but on film and in motion, absent any sense of organic emotional momentum, it just plays like an exercise.

His knack for concocting iconography ought to have been just the thing for propaganda. How to show that the crusaders are evil? Show one tossing an infant into a fire! Done. This is certainly some species of genius. But in practice, even that shocking image slots into the thudding editorial rhythm as just another problem solved, another concept executed. It’s juice-less.

In fact it’s funny to me that “formalism” was what the Stalinist regime claimed to revile, since that’s the perfect word for what goes on in a piece of insincere craftsmanship like this. Formalism is the shell left over when the heart is denied; it’s what artists have to fall back on when they’re assigned to churn out propaganda. Only art produced in bad faith deserves to be called “formalist.”

I guess all criticism is projection.

Every work of art stems from some underlying worldview, and thus embodies it. So whenever the Soviets denounced a work as “formalist,” they were evading the work’s actual point of view by denying that it had one. This shows a remarkable lack of faith in their own ideology; otherwise they would have confronted competing ideologies head-on. (Deriding a work as “capitalist” is at least a genuine attempt to assess its outlook.)

From an audience perspective, “formalism” is really a measure of pacing: does the mind have time to kill, in which there is nothing better to do than be concerned with form? While watching Alexander Nevsky, I idly imagined re-editing the action down to its intrinsic dramatic rhythm, eliminating all the deadly moments of “art appreciation.” That movie would be much shorter.

Superficial comparison to Dreyer’s Joan of Arc occurs to me; both films are heavily stylized medievalism made with a photographer’s eye. They share certain textural qualities. But Joan of Arc moved me, seemed like an obvious success. The stylization and artifice there always seemed to surround and serve intensely human, emotional concerns. So maybe the real problem with Alexander Nevsky is simply that there’s no Falconetti here; there’s no living face to turn on my human sense, my sense of meaning. Nikolai Cherkasov as Alexander Nevsky looks to me like a middling substitute teacher, the kind who keeps coming back but whose name you never take the time to learn.

I understand that pageantry works on a different level than normal narrative, and that Alexander Nevsky is trying to be a pageant. When the spiritual component feels so incredibly thin, that can also mean that the true spiritual component lies very deep. All spectacle is spiritual at a pre-propagandistic level, a subconscious level.

But watched that way, as pure apolitical image-glorification, the movie gives the constant feeling that the things in front of the camera are failing to be as transcendently epic as the vision demands. When Nevsky shakes his locks free of his helmet in glorious low angle, victorious atop his steed, it looks completely silly and insufficient. Nice try. That’s okay, Sergei; we get what you were going for.

This movie needs to be about a hundred feet tall to work. That’s why Prokofiev’s cantata, the music separated from the film, is a far superior piece of art. Music is born a hundred feet tall.

Alexander Nevsky is so profoundly dusty and limited that it can actually be hard to remember that the people making it weren’t themselves dusty and limited, but modern men and women of 1938, with fully modern psychologies. Yes, even in the Soviet Union! I think that’s important to keep clearly in mind, if we’re to understand what the achievements and the failures are. In this case the unrelenting artificiality is both the achievement and the failure.

(I was planning to embed a Getty image here like I did last time, something like this, but I guess the license to embed doesn’t apply to all their images.)

I watched the movie on Filmstruck, which offers a much superior restoration and is all-around more authentic. The copy of the movie included on the DVD is a 1986 Soviet clean-up job that does not use the original soundtrack recording overseen by Prokofiev. That original recording is frequently cited as having shamefully poor audio quality, but to my ear it’s not so much worse than any number of other crackly 30s soundtracks. The DVD version replaces the music with a later re-recording (apparently conducted by one Emin Khachaturian, Aram’s nephew) that, once noticed, feels conspicuously anachronistic. (I think it also uses the expanded orchestration Prokofiev created later for the concert version.) Also the title cards are all reset in typefaces that would never have been used in 1938. I’m sensitive to such things.

However I still got the DVD out from the library because it has lots of bonus features that aren’t on Filmstruck. Setting aside the movie itself, the disc is a pretty good package. There’s a competent commentary by David Bordwell of the sort that I normally scoff at for being hopelessly academic in outlook, but in this case it seems like just the thing. What else is there to do with this movie other than rattle off observations about the shot compositions? That paradigm, the one I criticize as so stilted and fuddy-duddy and beside the point, is Eisenstein’s home turf. He laid the groundwork for that kind of talk and it fits his work like a glove sticking out of a helmet.

(Bordwell describing Eisenstein’s technique: “… never using one shot where two or three will do.”)

There’s also very well done 20-minute “video essay” by Russell Merritt on Sergei Prokofiev’s music, and his collaborative process with Eisenstein, with extended emphasis on Walt Disney as an influence. I found this far more rewarding viewing than the film itself. If it were on YouTube I’d link to it.

Merritt: “Eisenstein later wrote that working with Prokofiev’s music, and working with Prokofiev to develop new theories of film music, were for him the only enriching aspects of Nevsky.” That’s about how the movie feels.

Plus there’s a whole other movie on the disc, too. Sort of. Bezhin Meadow (which borrows its title but not its content from Turgenev’s story of the same name, which as you all surely remember was already addressed on an earlier episode of this program) was Eisenstein’s previous project (1935–37), but was canceled before release, suppressed, and ultimately destroyed. However, Eisenstein apparently had the habit of keeping a private copy of the first and last frames from each shot of his movies, and these survived. In 1965, a director and a film historian found them and put them together into a kind of 25-minute filmstrip version of the entire movie, with intertitles taken from the original script. That assemblage is all that remains of Bezhin Meadow, and so to give a little extra dimension to the boxset, Criterion has included it. It’s not a movie, and it can’t really be watched as a movie… but as a record of a lost movie it’s extremely generous. There’s so much here — you can see what every single shot looked like, clear as day! — that your instincts tell you surely the rest of the movie isn’t really lost. But it is.

Here are the two things I’ll say about Bezhin Meadow:

1) I can’t tell whether I would have enjoyed the movie — as with so many Soviet works about everyday heroes living on communes, the dramatic arc seems awfully suspect — but I can easily tell that this was a more interesting and soulful piece of work than Alexander Nevsky. The faces are better. The sense of humanity is stronger.

2) Since Eisenstein already treated film essentially as a moving slideshow, the filmstrip format actually flatters him. The fact that he had the inclination to keep a souvenir frame from every shot is, I think, pretty indicative of where his personal satisfactions lay; in that sense, it’s not aesthetically arbitrary that this is what happens to survive. It feels like he was at some level a baseball card collector and this is a complete set. His projects were conceived as sequential photography, and the photography is certainly quite good. He would have been a natural for those old Richard J. Anobile books. (Remember when I said I fantasized about editing Alexander Nevsky down to its natural internal rhythm? I think this might be actually it: a series of still images, a few seconds apiece, about 20 minutes total.)

Bezhin Meadow was going to have music by Gavriil Popov; in its absence, Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 6 (and Zdravitsa) has been slathered over the proceedings. Good music, but not very well matched to what’s going on; generally it only serves to confuse the drama, which is already fairly confusing.

Luckily I don’t feel obligated to try to puzzle it all out. As far as I’m concerned, this is just a bonus feature, and by watching it at all, I gave it its due.

Criterion includes some on-set photography and a bunch of related articles to page through onscreen, including Eisenstein’s groveling official mea culpa. Fine. Can’t say I read every word of it all but I sure did page through!

If you read books about film music, you’ll often come across this silly diagram that Eisenstein made of a sequence in Alexander Nevsky, showing how blips in the music supposedly correspond to blips in the image — the premise apparently being that the viewer is in some sense always “reading” the image from left to right, as though it were a written document. This is an obvious absurdity, and is indicative of Eisenstein’s eccentric, anti-intuitive way of relating to the medium. It certainly has nothing to do with the way most directors use music. But the diagram is so compelling qua diagram that people have a hard time resisting the urge to reprint it. It’s a classic.

Having finally seen the film, I realize that because Eisenstein’s technique is so utterly formalist, this stupid diagram actually makes a certain sense after all. Incidental music generally seems to apply itself to whatever is most emotionally salient about the drama in a given moment. Within the deadened formalist outlook, a pure visual arrangement of e.g. individual figures interrupting a flat landscape does indeed start to seem like it’s probably the most significant thing going, and the music accordingly starts to seem like it’s probably commenting on the shot composition… because what else is there?

I’m a big Prokofiev fan — he’s right up there on my shortlist of favorite composers — and I must say that Alexander Nevsky has always seemed to me rather overrated among his works. The majority of the score is in his Soviet monumentalist mode, glutinously expansive. Prokofiev injected himself with some kind of Stalinist novocaine to produce works for the state, of which there are many in his late-career output. They’re certainly not worthless, but it helps to be in a stupor. And yet Alexander Nevsky often gets packaged alongside things like Lieutenant Kijé and the Scythian Suite, which are to my ear much more immediately and consistently rewarding.

The reason it stands out in popularity above Prokofiev’s many other Soviet-era works is surely the long “Battle on the Ice” movement, which paved the way for all manner of Hollywood excitement. The first section, when the crusaders emerge from over the empty horizon and then charge all the way to the waiting Russians, is the clear standout and by far the high point of both the film and the score. In fact I think many people would say this is one of the high points for film music as a whole. The bumping two-note ostinato of the charge, which creates an ever-expanding anticipatory tension, is a perfect musical conception. John Williams stole it outright for Jaws, and who can blame him.

So that’s of course our selection (despite a couple of brief spoken interruptions). Apparently in Prokofiev’s original score this cue was called Свинья, “The Swine,” which refers to the wedge-shaped attack formation. You can hear this same material recorded in rich symphonic stereo in a hundred concert recordings. Here, for a change, enjoy the original crackly, noisy, sloppy, small orchestra recording from the film.

You know, it might just have been the worst possible timing for me personally with this movie. Right now I’m in a moment where I’d really prefer to be transported than be asked to contemplate something dispassionately, so this felt like a singularly unfortunate choice. Every now and then, while I was trying to get through it a second time with the commentary, I would notice the image out of the corner of my eye and suddenly think, “Hey, this is kind of cool to look at. I see how at a technical level this is an interesting piece of work. Maybe it isn’t actually as bad as all that.” It was just never able to sustain that impression under direct attention. And I accept that maybe that was simply a question of where my head happened to be.

But that’s what I’ve got to work with.

Let’s get this over with already! I just want to be watching other movies.

Oh right, oops, next is just more Eisenstein. I hear they’re gonna be better, though. Let’s see.

[OOP 9/2009]

[OOP 9/2009]

(OOP 9/2005)

(OOP 9/2005)

(OOP as of 11/07)

(OOP as of 11/07)

(OOP 4/2013)

(OOP 4/2013)

(out of print September 2004)

(out of print September 2004)