2000:  [OOP 9/2009]

[OOP 9/2009]

(replaced by equivalent “Essential Art House” edition)

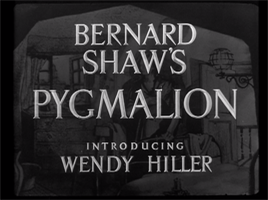

directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard

screenplay and dialogue by Bernard Shaw

scenario by W.P. Lipscomb and Cecil Lewis

Criterion #85.

Streamed from FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel.

My mode at repertory musicals: trying my skill against theirs with the familiar material; asking “have they aced it?” rather than just watching. Like catty operagoers have done for centuries. I can’t help it. This is what comes of spending too much time with scripts and scores: everything starts to look like scheme and execution instead of pure phenomenon.

Even in that petty light this comes off very well, besting My Fair Lady at its own game.

Bursting into song actually suppresses dramatic pathos; it prematurely resolves all dissonances of sentiment. There is something truly poignant, not just structurally poignant, in this straight version. A full human being has too many feelings for any one song, and the question of what constitutes a full human being is at issue in this story. Pygmalion may be a sort of fable but it is not a fairy-tale.

A 20-second scene in Eliza’s home at the start pays dividends later that the musical misses: we understand that she has always been her own person; she is not Higgins’s creation. Galatea was a stone given soul; Eliza is already a soul, given a new stone setting, one among many possible. Her awakening is not her transformation itself; it is simply learning that she has the ability to transform.

The musical insinuates a Cinderella lust-for-glamour, a priori materialism, which ruins the play’s truly radical message: that all people are already equal and the trappings of class are arbitrary. Fancy dress does not actualize Eliza. Why would it? It is significant that she could not have danced all night; after all, whoever said she wanted to? Her uncertainty about what she wants is at the heart of the play and not to be plugged up for convenience.

The work montage here is far superior: Eliza has no clueless, tone-deaf phase; she’s immediately capable and industrious; the regimen of exercises seems coherent and believable; Higgins’s confidence seems to jibe with his abilities. We see her will and his; the only reason either of them has to sweat is the time pressure. There’s no vague, mysterious block to overcome first. That is to say: the Broadway contrivance of an impasse to precede a “eureka” markedly weakens the message that all that stands between Covent Garden and Buckingham Palace is weightless fuzz. The mysterious block, the sword that must be pulled from the stone, is none other than our projected prejudice: that an ordinary flower girl could obviously never pull this off, but a Chosen One could. (i.e. Audrey Hepburn.) This is not good faith.

Spry, younger-seeming Higgins is much preferable to the standard tweed. Personality comes into sharper psychological relief the less it’s telegraphed by physique and costume; we have to contend with the ways his outlook is available to us, too. Higgins’s attitude, its virtues and sins, becomes the focus of this script. This is the richest vein in the material and surely Shaw’s point of fascination.

His contempt is for the highs as well as the lows, and none of it is felt; in his abstracted way he loves all, he just doesn’t know it. He cavalierly tosses Eliza money that changes her life, because he enjoys the British forms and they include charity. But as he smirks, we hear uplifting church music all the same because the form delivers its substance no matter the spirit. Who’s to say this isn’t truest love?

It is only Henry’s lack of conventional empathy that allows him to genuinely help Eliza’s inner self. By his complete failure to feel her as an individual, he grants her uniquely unconstrained potential to be an individual. Being felt can be repressive. And yet we need it from one another; being a “consort battleship” is nobody’s heart’s desire. His problem is not that he cannot give but that he cannot receive. And everyone needs to be received, to be found. A moving portrait of the true nature of sympathy, and of empathy: each is the price of the other’s power.

Eliza’s Turing Test is the same for all of us; all of society is a Turing Test. If the difference can’t be told, there is no difference.

Consider the handling of Wendy Hiller’s physiognomy. Is it regal beauty or mask-like grotesque? Don’t worry: the movie will decide for you, scene for scene. When she emerges for tea dressed like Pinkie it’s parody, but her climactic presentation as the belle of the ball is quite serious. If the audience is drawn in — and we are — then we are part of the social conditions under critique. I felt a slap being administered to every “taking off her glasses to reveal her beauty” scene in cinema. Who says? The male gaze is just one of a thousand arbitrary frameworks. There’s also the Queen-of-Transylvanian gaze, etc. We can’t stop gazing but we can at least try to remember that everyone is protean.

Hiller is completely excellent. Shaw’s personal choice for the role and no wonder. She gives much more than one is accustomed to seeing given. In the ostensibly comic bathing scene she lets in genuine horror and indignity. This encapsulates the meaning of the whole story.

Apparently Getty allows you to embed images for free.

From the above it should be clear that as regards the ending my sympathies are 100% with Shaw, who disapproved vociferously. Henry thinks “tower of strength” is the highest possible approval; Eliza realizes that to the contrary she is in fact a person and says “goodbye.” That is rightly the culmination of the action and should suffice as its terminus. The sugary tag — invented for this movie and then carried over into posterity by Lerner and Loewe — is just commercial timidity.

In musing on the movie I came across many interesting side channels relating to Shaw, his work on the screenplay, the play’s past and future, etc. etc. etc. Originally I thought to discuss such things here. But the material was so plentiful exactly because it’s all such well-covered ground. Why strain to add to that when I’ve already said my piece?

First Criterion appearance of Koenig’s manometric flame apparatus. And probably last but one never knows.

The image is pretty bad. The transfer isn’t great and the film needs restoration. The streaming and DVD versions are the same.

The DVD offers no supplements. FilmStruck has a 3-minute TCM-style interview-cum-promo, “David Staller on Pygmalion (1938),” which is fine enough for one of those. I certainly admire the craft of the TCM montage team; they can make any old movie look superficially lively and promising. But that’s also the problem: their house style is homogenizing and ultimately condescending to the material. Especially their music. It all tends to feel a bit like in-elevator entertainment at a mid-range hotel. Still, simply as 3-minute propaganda pieces I can’t really fault them.

Now that streaming has entered the building as a viewing option, the supplement situation is likely to become quite complex and potentially sticky. Some of the original disc supplements are available at FilmStruck — but not all. Some supplements have been newly produced for FilmStruck and do not exist on disc. Some films are available to stream in new transfers not yet released on disc (see the title cards in the previous entry for an example). At present I can make no promises about what my policy will be — that is, what will count as having watched a given Criterion release and what won’t — but rest assured we at broomlet take such matters very, very seriously and we have top men looking into it right now.

Arthur Honegger of all people! The Criterion site database includes two other films with music by Honegger but neither of them is part of the main numbered series, so this is it.

I had no idea he had it in him. I knew he did pictorial music but not such genial commercial stuff as this. Though he does sneak in some quirky modern corners and angles. (The striking little oscilloscope cue early on.)

The idea of “My Fair Lady as composed by Arthur Honegger” is amusing to me. Some of the work has already been done:

Not to mention:

Official selection is the main title and introduction:

The tune in the strings starting at 0:45 functions as Eliza’s theme and gets several treatments over the course of the movie. Not that I noticed on first viewing.

The score overall is quite good. Never released or rerecorded. According to a Honegger biography I found, the manuscript is mostly lost. Then again the same biographer wrongly asserts that most of Honegger’s music was replaced in the film — which at first I thought must account for why it didn’t sound like Honegger, but which actually just seems to be a bit of confusion on the writer’s part. MGM made their own American cut of the movie that did indeed replace most of the music with stuff by house composer William Axt, and also re-edited a couple of scenes, but nobody ever watches that version these days, for obvious reasons. Seems like the biographer came across a copy of that and mistook it for the original.

Or else I’m being duped and the music you just heard is really by Louis Levy or someone. But I doubt it.

For my untenanted location still, I had to chase the editor all around; he didn’t seem to want to let me have one. Last time I was so stymied was Brief Encounter, and lo and behold, the editor of Pygmalion was David Lean. I guess he must have made it a real point of principle that there should be human activity in absolutely every frame.

Almost settled for a frame with a sliver of person in it but then finally found this one. Whew.