developed by Metropolis Software House (Warsaw, Poland)

first published by Metropolis Software House, February 26, 1995, for DOS, 49 zł (= $20 (1995 rate))

first published in the US as “shareware” by Union Logic Software Publishing, April (?) 1995, for DOS, $29.95

GOG package ~25MB. Actual game ~15MB.

Played to completion in 3 hours, 4/25/15–4/26/15.

[video: 2-hour complete playthrough]Still working through the GOG free-for-all. This one was added to GOG on April 1, 2009 as the 100th game in their catalog.

Though it isn’t at all obvious from their friendly English-language website, GOG is actually based in Warsaw. It is a subsidiary of an older Polish company called CD Projekt. In 2007, CD Projekt had bought and absorbed Metropolis, the developers of Teenagent. Metropolis had declared Teenagent freeware way back in 1999; it only took four years for the company to feel they’d advanced so far beyond it that selling it actually detracted from their reputation. So basically: the parent company of GOG had this extremely silly game in their pocket, of sentimental value to Poles generally and to its developers specifically (some of whom are still on staff), so they decided to make it their 100th game as some kind of April Fools’ goof, or at least half-goof.

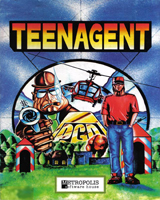

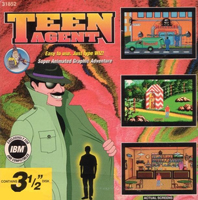

Going in, I knew this was going to be a clumsy old third-rate Polish adventure game, resurrected as a nostalgic indulgence for the Warsaw office that grew up with it. Even if you haven’t watched any of the gameplay video, just the box images above should give a sense of the production quality: verging on the homemade. So it was to my surprise that I found myself genuinely charmed and amused.

There were tons of intensely clonky amateur adventure games being passed around in the 90s, made by teenagers who, like me, were totally enraptured by the LucasArts games, and then, unlike me, felt compelled to try their hand at the craft. Generally those games were riddled with compulsive references and quotes from Monkey Island or Zak McKracken or the like. The real LucasArts games already had an offhand, self-deflating manner that frequently descended to frame-breaking “in-jokes.” So fans who were eagerly following in their footsteps felt all the more encouraged to indulge their impulses toward geeky mimicry and allusion; it was already a part of the style. Unfortunately it also made most of those games basically unbearable. Well-made adventure games appeal to the 12-year-old boy in me, but the creations of other 12-year-old boys don’t.

(It always seemed dumb to me when things like Stone Soup magazine implied that kids really want to read the writings of other kids. Trust me, they don’t; they want to read things that are good. So much stuff is directed at kids with this clueless and insincere message of “empowerment” based around the premise that kidhood is a political identity like race or religion, and that kids inherently want to band together laterally and form a community of mutual respect. Pshaw!)

Teenagent has very much the naive look and feel of those games. It initially seems like something made by 12-year-olds. But it quickly becomes clear that if so, they’re the very best kind of 12-year-olds, the kind who pounce on any opportunity for silliness and never settle for mere good form. In the game, you get a feather from a chicken. When you examine it in your inventory, the game says “It’s kicking ass.”

I feel like that about sums it up.

Because the game was not made by actual American 12-year-olds, whose attention would falter at some point and leave gaping holes, but rather by totally goofy Polish programmers who were capable of following through, there’s actually a completely functional game here, surprisingly generous of graphics, animation, and dialogue. For complete artlessness it’s fairly skilled. So it’s sort of the ideal 12-year-old’s game, something that could only be made by adult (well, at least college-age) Europeans. Europe has less of a stigma against childlike silliness. It’s kicking ass.

Okay, but the game is not in fact ideal. I wish I could say that it’s a folk-art delight through and through but it’s not; it’s got actual problems. First of all, it has super-dopey music that, though amusing at first, unfortunately exists only in very very short loops, which repeat incessantly. After 45 minutes of a particular 30-second inanity, there’s no longer any way of construing it as naive charm: it’s undeniably a flaw.

More importantly, I can’t recommend anyone sit down and play it through because it’s not fair enough. I had to cheat eleven different times, which I think is a record for me and adventure games. The logic is absolutely ludicrous, which is all in good fun (and par for the course), but there aren’t nearly enough hints built into the game to nudge the player toward the correct nonsense and away from the incorrect. There are lots of actions that if you attempt them, you just get a generic “That doesn’t work” type response, when you ought properly to get a “Good idea, but I think I need something a little smaller” type response that would help guide you where you need to go. When your inventory fills up with 20 objects and there are 17 different rooms available full of stuff to “use” them all on, trial and error is not a viable way of proceeding, and yet players will inevitably have moments where they feel they have no other option. I had eleven such moments — well, actually, many more than eleven, because a lot of the time my trial and error paid off. The eleven cheats came when even my attempts to exhaust all likely possibilities came to nil.

If you gave me just the game text to revise, without adding any new animations or interactions, I think I could make it much more fair, by adding lots of little nudges to narrow the options. I could also fix various infelicities in the Polish-written English (“All I care about is the respect of the science society respect.”), although I must say I was impressed by how few there were, and how idiomatic a lot of their goofiness had been made to sound. Even the pun of the title (get it?) suggests an impressive fluency. Sort of.

I counted roughly 100 actions in this 3-hour game. That comes out to better than one every two minutes, which is so markedly different a pace from the four-minute trudges of the prior two games that it feels almost like a different species. It reminded me a little of those French Gobliiins games, which packed the maximum number of silly puzzly interactions into each area. In such a game, the sense of flow becomes quite different: most of the gameplay overtly takes place in completely frozen narrative time, like song-time in a musical, whereas in the American games (and the UK games I’ve just played) there is more of an attempt to keep alive the strained impression that every puzzle relates directly to the narrative and that the narrative is always in motion, even though it has to slow to a crawl while you deal with the details. I find the European style more conducive to daydream-y play, but the impression they make is also more frivolous.

Of course “frivolous” doesn’t even begin to describe what goes on here.

The second part of the game is all about trying to get into the mansion of the villain; you have to attempt to get in five different ways, one of which is to sneak in through a secret tunnel, the entrance to which is a trap door.

The trap door is in a clearing in the forest, under a beehive surrounded by bees. You refuse to go near enough to open it while the bees are there. The solution is to throw a dart at the beehive, which pierces it and lets some honey drip out, instantly attracting a bear from offscreen, who lumbers on and then quickly exits pursued by the bees, clearing them from the scene. There is no actual dart in the game: you create a makeshift one by sticking a needle in the front of a pinecone and a feather in the back. The needle you find by searching a haystack. The feather you get by kicking a chicken. The pinecone is initially seen stuck to the back of a hedgehog, from whence you refuse to simply pick it up, because you don’t want to poke yourself on the quills. The way you get it is by bringing the hedgehog a fake plastic apple and telling it you’ll exchange the apple for the pinecone; the hedgehog accepts this deal and turns over the pinecone, then storms off in dismay when he finds the apple is fake. You get this plastic apple from a bowl of imitation fruit in an old lady’s living room. She won’t let you take it without listening to a tedious story, which you refuse to do; the only way to get it is to surreptitiously swap it, so quickly that she doesn’t notice, replacing it with a “large nut.” The nut is initially found on a high branch of a tree, out of reach, but next to a squirrel. If you talk to the squirrel and ask it for the nut, it refuses. However, if you talk to it four times in a row, eventually you anger it so thoroughly that it hurls the nut at you… but it falls into some grass, in which it can’t be located by hand. To retrieve the nut from the grass you have to rake it out. Unfortunately when you first find the rake, it’s old and damaged and its remaining teeth are too far apart to be effective. To restore it to usability, you have to bind the teeth closer to one another with a ribbon. The old lady’s pretty granddaughter gives you the ribbon, to remember her by, as thanks for having given her a heart-shaped chocolate in foil. The foil wrapper is found loose on the ground and you must apply it to the chocolate yourself. Furthermore, the chocolate, which is given to you by the guard in front of the mansion as consolation for your not being allowed entrance, is initially round rather than heart-shaped. You must bring it to a cabinet with heart-shaped holes, and push it through one of the holes, which trims it.

That’s how you get in the trap door.

If you are chuckling and shaking your head at such a cavalcade of stupidity, you are in fact enjoying the game as it was intended to be enjoyed. Maybe you’d like it after all.

Credits. The leads here are still in the industry and making prominent games.

Adrian Chmielarz: programming, “ideas”

Grzegorz Miechowski: animation, “ideas”

Andrzej Sawicki: “ideas”

Tomasz Pilik: additional animation

Andrzej Dobrzynski: backgrounds

Radek Szamrej: music

Peter Wells: “translation help”