developed by Origin Systems (Austin, TX)

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire (1990)

executive producer: Richard Garriott

produced by Jeff Johannigman

directed by Stephen Beeman

story by Aaron Allston

Ultima Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams (1991)

creative director: Richard Garriott

produced by Warren Spector

directed by Jeff George

dialogue by Beth Miller, Raymond Benson, Steve Cantrell, ‘Manda Dee, and Paul Meyer

More games that I can’t handle.

Yes, it was only a few months ago that I was admitting that I couldn’t handle Ultima IV (1985). But hope springs eternal. And so does obsessive completism. These were on my list, so I had to try them. I had to hope!

Oh right, obsessive completism:

2/13/13: I buy Giana Sisters: Twisted Dreams (2012) on sale for $4.99. Good enough to finish, but I only bought it because it resembled Donkey Kong Country Returns (2010) and the comparison didn’t flatter it.

2/25/13: It comes to my attention that during the past year, three more free games have appeared in the GOG catalog. I instantly add all three to my account, with no consideration whatever for what they are.

Two are the games I’m about to address. The third is a freeware first-person shooter called Warsow (2005–12), which won’t even get its own entry; I took my obligatory look at it last week and found that it’s an arena game where you battle head-to-head with players on the server. I have given myself an out on multiplayer-only games before and I’m doing it again. Those people scare me.

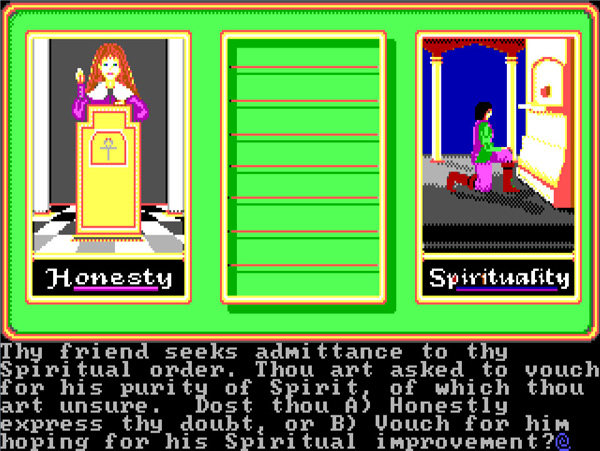

Things I was able to relish about these two “Worlds of Ultima” games:

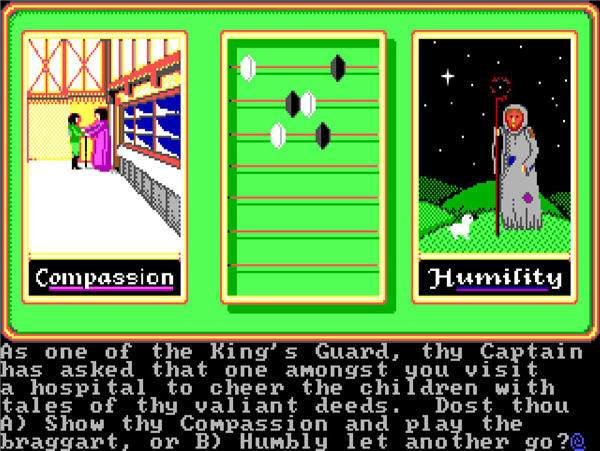

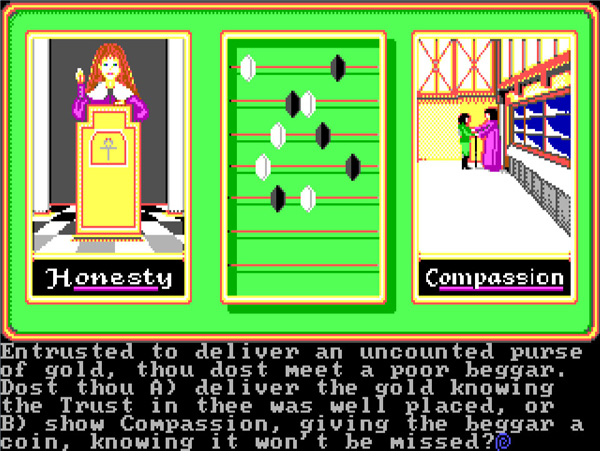

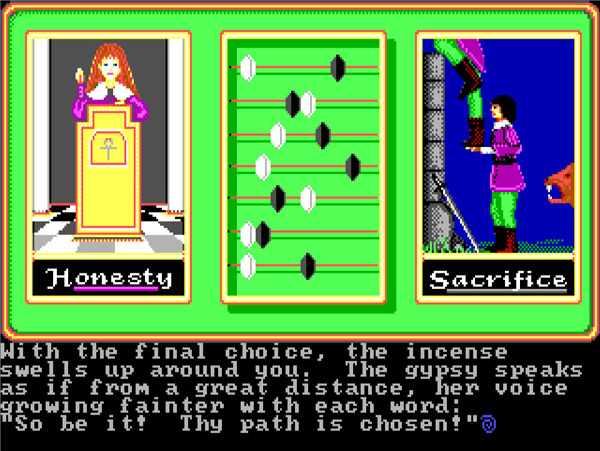

• A world of bitsy candy-like graphics with black borders.

A magazine I bought in 1992 had a screenshot or two from Ultima VII (1992), the subsequent release in this series — something like this or this or this — and despite knowing full well that RPGs were not my cup of tea and that I would never buy the game, I extracted a lot of imaginative pleasure from those couple of printed images.

The idea of a vast world of little marzipan goodies, all fixed in place and made wonderfully incontrovertible by their black outlines, was somehow a dream I had already had; these images just gave it body. The extreme high-angle view, just off to one side from being directly overhead, felt psychologically accurate; it would be from just such a vantage that I would silently look over and in on the soothing mysteries of this world-vision. The roofless buildings, both indoor and outdoor. The surface textures supernaturally prominent yet still restful. I could go on.

The present two games — which are experimental pendants to the main Ultima series — are made with the engine from the preceding game, Ultima VI (1990), which has significantly more primitive, less delicious graphics, but still hints at some of the same satisfactions. The doodads here are too small and harsh to impart that restful textured quality, but the bitsiness brings its own appeal. If you’ve ever taken obscure pleasure in looking at a screen full of Mac or Windows icons, you can find that pleasure here. Here’s a screenshot from Savage Empire, picturing a village feast with a bunch of food in it, which looks a lot like a computer desktop that has been “auto-arranged.” Is it actually food, or is it just doodads? These games let you savor the ambiguity of living in a world of icons.

• A stab at variety.

To this day, RPGs are still almost always about Dungeons & Dragons. There’s no inherent structural or thematic reason why this should be the case — just cultural inertia. These two games are attempts at expanding into other kinds of classic pulp material. The Savage Empire is “Lost World” safari fantasy — a jungle valley of warring tribes, dinosaurs, and lizard people — and Martian Dreams is goofy steampunk, about a 19th-century rocket to Mars, featuring a full roster of random historical figures. (Sigmund Freud, Buffalo Bill, and Rasputin, together at last, on Mars.) Neither of those premises cries out to me, but I’ll gladly take either of them over more of the same old mytho-medievalism.

• An expansive sense of the long haul.

Wherever you’re headed, in this kind of game, it’s still a ways off. You have a lot of chores to do before you can get there. So don’t be in it for the reward. Be in it for the journey. Or not even the journey: the condition.

In checking out Youtube “Let’s Play”s of RPGs, when I inevitably skip forward to the video called e.g. “part 31 of 32,” which is the videogame equivalent of flipping to the end of a mystery to see who done it, invariably the impression I get is that the long-awaited climax is hardly more interesting or consequential than any arbitrary point in the middle. And there’s often a grudging or perfunctory quality to the victory scene at the very end.

A lot of video games over the years have ended with a lame “You did it” message and little else; RPGs, which take many tens of hours to complete, are the worst offenders. It seems almost like a symptom of embarrassment, or fish-out-of-water awkwardness: “Please don’t ask us to claim this was all worthwhile. Please don’t ask us to claim this was anything. It was just the framework for a certain flow state. Can’t we please just get back into the game instead of having to think about it?”

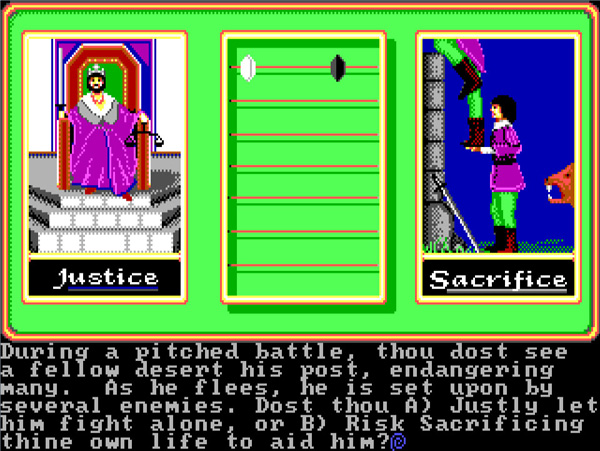

I like the idea of games as flow state above all. I’m attracted to the idea of “quest” being micro-event (when some guy in a hut says please kill the snakes in the basement, so you do, and he gives you gold) and macro-event (when the premise of the game is that you have to reunite the empire, which you probably will in part 32 of 32, fifty hours from now) — but not plain old event, the scale on which I tend to do all my agonizing and overthinking. On that everyday “well, what ought we to do next” scale, these games leave a strange quiet mental space for the player to set up camp. Do your thing; be our guest. In a sense, this is what’s meant by “Role Playing”: the game is not as much about what you’re doing as it is about how you’re being.

And despite never taking to these games, I really like that particular aspect. In theory.

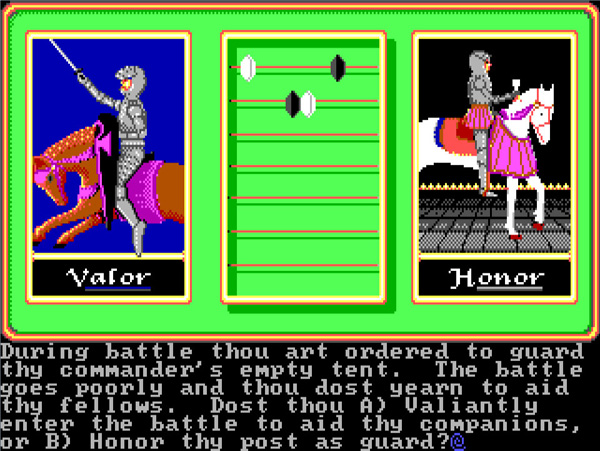

• “Strange quiet mental space” generally.

This is the principal thing that I feel games have lost touch with in the past 20 years or so. That opinion isn’t just nostalgia for my own past, because I feel it even when I dip into games that played no part in my childhood, like these. It’s like the game’s authors and their intentions are audible only as a distant tinkling of cowbells, many miles from where I sit, encountering the game on its own inanimate terms. It’s me alone with it, in my own zone. In more recent games I have a sense of authorial neediness, or micromanagement, in my face almost constantly; the games speak with human voices that make me feel crowded. Whereas this older kind of game is as generously welcoming as only privacy can be.

• Also I won’t deny I get a kick out of any opportunity to hear the old Adlib MIDI sounds, but that is just nostalgia.

Okay, that’s what I liked.

Now a horizontal.

Actually, how about I do the videos now.

There are no trailers for games this old, which is why I didn’t put these at the top. The following clips are just for illustrative convenience, and to satisfy reader curiosity. Don’t watch them beginning to end unless you really want to. I certainly haven’t.

Here’s the first 15 minutes of The Savage Empire. The intro lasts about 4 minutes, and then the game starts with a lot of dialogue. Start at around 10 minutes in if you just want to get a sense of the gameplay.

And here’s the first 15 minutes of Martian Dreams. The intro to this one is pretty long and wacky. Again, skip forward 10 minutes for a sample of the gameplay.

Okay, now for the things I was unable to relish about these games.

This part briefer. I take less and less satisfaction these days in elaborating on my discontents. Plus the only form of writing that’s actually natural for me is the bullet points themselves; the rest is a nervous grind, here dispensed with.

• The sense that there is no place to invest myself; no particular “thing to care about.” Any given detail is just a utilitarian cog in the machine, and the machine’s only function is to turn its own cogs.

• The rational-analytical-statistical compulsion. This is what has always blocked me out of RPGs and I still haven’t found a way to embrace it. I want to marvel at experiences, not at systems. Experiences are not systems.

• An emphasis on reading but not on words; i.e. too much bad writing. I readily tolerate tone-deaf dork prose when it only appears in short bursts. But if the focus of a game is going to be on a written story with many screens of text at a time, I can’t put aside the sense of alienation I get from insensitive writing. It feels to me like being trapped with insensitive people. Which I guess is the phobia that continues to define me.

I played these games for a couple hours apiece, sincerely hoping that a sense of trust would set in, so that I’d be able to enjoy long sojourns in these vast quiet spaces. But it never did. I never stopped feeling like I was playing a game meant for another sort of person.

Some day, I swear, I will play an RPG for real.