directed by Seijun Suzuki

written by “Hachiro Guryu”

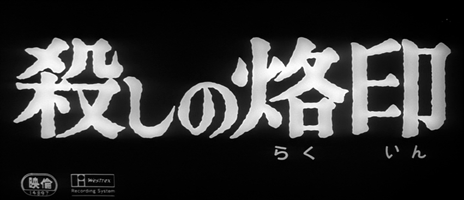

Koroshi no rakuin. The English title is Branded to Kill. But what, exactly, does that mean?

殺し, koroshi = murder, killing

の, no = particle comparable to “of”

烙印, rakuin = mark, brand, stigma

I’m guessing that what this adds up to is something comparable to “The Mark of Cain,” e.g. “The Mark of Murder” or “The Mark of the Killer.” The plot involves a professional killer who after bungling a job becomes himself the target of a killer. Something concise and ambiguous like “Killer’s Mark” that points up the circularity would be a good translation. “Branded to Kill” is not.

Criterion #38.

A sign of our cultural times: artist interviews full of “No, [the thing you just asked about] doesn’t have any special meaning. I just kinda did it, who knows why” — but presented as though this is our enlightening glimpse behind the curtain. (“Huh, think of that! He just kinda did it and it didn’t have any special meaning! A fascinating insight into process!”)

This is a minor symptom of the movement to embrace “low” as “high.” Twenty-first-century man sez: Comic books are art too! Wow Mr. Lee, when you invented the rich and worthy cultural text of Spider-Man, what was the thinking behind giving him no mouth? “I just kinda did it, who knows why.” Wow! Now I know it’s great art because it’s full of mystery!

I don’t think that’s entirely wrong thinking. If there is any single “the thing about art” about art, it’s that an explanation is no match for it.

But I do think it’s entirely wrong thinking to embrace the low AS HIGH. The artist interview is itself an artifact of a Romantic attitude that can only confuse the essence of Spider-Man. Or more accurately: the belief that an inquiry into intentions is obviously relevant… is a Romantic artifact. There’s nothing wrong with a little knowledge, but there is something wrong with the assumption that knowledge is always important.

The Criterion Collection makes me think about the importance of curation, by which I really mean context. I feel a little sad that those words now mean the same thing for film, because I don’t think museums have done our understanding of the visual arts any great good. The sterility and snobbery of “curation” are a little chlorine in your water. Clean clean clean! and it also doesn’t taste good any more. When I look at things like this I can’t help but fixate on the question “did the twit with the stamp have no sense of shame?” Children should be seen and not heard; go to your room!

But that’s common practice. The twit with the stamp is higher than a king. The Grand Federal Doggie pees on each item submitted to the Library of Congress to mark it; you should be so lucky!

Criterion wants to offer you the full Steve Jobs package: the product looks sleek because it is sleek because rest assured it’s been good and curated by the Grand Cosmic Doggie. You are so lucky, consumer! And of course we all know that for movies on DVD, that means a great pageant of the inquiry into intentions: artist interviews, behind-the-scenes, historical context, archival ephemera, accredited experts, information, information, information! You think you knew water, but you haven’t REALLY had water until you’ve had CHLORINATED water. It’s cleaner than the real thing!

This movie — there we go — this movie is a Spider-Man with no mouth. There are several interviews on here wherein surprise surprise, they just kinda did it, who knows why.

It’s screwy. My feeling is that the screwiest art usually emerges out of some sort of folie à deux situation (but more than deux, e.g. a folie à Japon situation) – nobody has to try to be screwy because everyone present has already mutually embraced it. Sometimes with a grin, sometimes with a straight face. I think this movie was made in a spirit of fun, but a screwy one. The main thing is that the premises of this movie’s screwiness are well outside and beyond the movie. It is not authorial in the Romantic sense. For those of us watching it, the important thing is not how much we know about where it came from. Much more important to me is where I am and how it’s coming at me.

Criterion puts it in a numbered box and sells the box. But that’s exactly where it’s not coming from. And this is where “it’s kind of amazing!” comes in. If there is no natural order to culture and we have to depend on curators to keep things in view, there’s no longer any assurance that we will be exposed to things that don’t merit curation. And yet we want them around. High vs. low was never part of our emotional reality. So we rig up a bullshit case to convince the curators to stock regular old crap, because “it’s actually kind of amazing!”

This is why I disliked the ultimate message of Ratatouille. The soulless snooty critic is reminded of his soul, reminded of the emotional reality of food rather than the sterile context of pass/fail high/low pretension that has killed the joy of life. So then HOORAY he writes a positive rather than a negative review within the sterile, pretentious context and thus validates the hero within the sterile, pretentious context. Whew! Don’t worry, kids, your dad was wrong to yell at you that you’re wasting your life, because the reviews are in and it turns out your beloved Spider-Man belongs at MoMA after all! Videogames belong in the Smithsonian! It turns out that your authentic self isn’t embarrassing after all because it’s KIND OF AMAZING! You go girl! Let your freak flag fly, in the manner of e.g. Lady Gaga! She’s not afraid to be real!

The original Criterion essay on this movie is by John Zorn. It’s short, and the gist is, “I happened to see this on TV when I was in Japan and I had an experience with it.” That was the most genuinely useful, appreciation-deepening thing that was offered to me in the entire package. (And it’s not in the new package.)

The movie is a gangster movie, sort of, but it’s off its own rails. It’s brazenly incoherent. I could list the crazy details but that would feel like telling a lie, the lie being “it sure makes an impression when this crazy thing happens!” Not necessarily so. My actual experience was sort of furrowed-brow bemusement, and a shrugging acceptance. I have other things to worry about than why this contract killer in an old B-movie has a fetish for rice-cooker steam, or whether I think that’s interestingly weird. It was a little interesting; not that interesting. (Rice cooker product placement, one of the interviews implies, for what it’s worth.) If I had been in a hotel in Japan and this had come on TV I’m sure the experience would have been much, much more intense.

Criterion callbacks: The story here, such as it is, is a close relative to The Killer. The artistic value is a close relative to The Naked Kiss. My thoughts there basically apply here.

Best thing on the disc was the amusing contemporary interview with star Joe Shishido, who talks candidly about his unfortunate cheek implants. (They seem to have been removed at some point in the intervening years.) In the middle of answering a question — sort of — he suddenly pulls out a prop gun and shoots it, which is one of the greatest moments I’ve ever seen in an artist interview. Take that, curators!

One thing I can say unreservedly that I enjoyed is the 60s-cool score by Naozumi Yamamoto. Harpsichord and harmonica, baby.

The music that opens and closes the movie is a bluesy song about a killer. I’m not sure that vocals suit our purposes, especially what with the spoken interludes, so here instead is a cue from the middle of the movie, a hummed version of the same tune. Preceded by a sting for a dead body, natch. Track 38.