directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

written by Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky and Andrei Tarkovsky

Criterion #34.

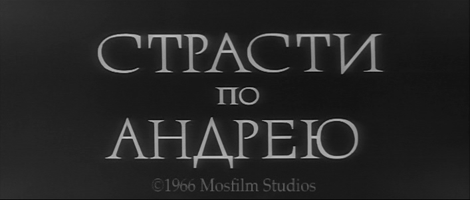

This is the movie you know as Andrei Rublev. Regarding the title, however:

The film was shot between 1964 and 1965. When Tarkovsky completed editing in 1966 he had given it the title seen in the frame above, which says “Strasti po Andreyu,” meaning “The Passion According to Andrei.” But this version was never shown. It was rejected by the Soviet authorities, who demanded cuts presumably relating to religious content, violence, nudity, and general un-Sovietness. Tarkovsky returned to editing and prepared a new version, 18 minutes shorter and altered throughout. In the process he retitled it simply Andrei Rublev. (Perhaps in response to Soviet discomfort with the explicitly Christian title.) This shorter version is the film that found its way into the 1969 Cannes film festival and was finally released a few years later.

Unlike every other release of this film, the Criterion DVD proudly offers the suppressed first version, reportedly sourced from a print that Martin Scorsese obtained on a visit to Russia. (The rumor online is that one of the editors had kept a copy of the suppressed version under her bed for 20 years and that Scorsese “smuggled” it out of the country.) Prior to the Criterion release of this material, it seems that this longer cut may never have been seen publicly.

So as titles go, the present film is pretty clearly called The Passion According to Andrei. But the packaging would have it that this is simply the preferred version of the film universally known as Andrei Rublev, which is accordingly what Criterion calls it. The back cover of the DVD makes clear that they are trying to have it both ways: it prints both titles as though the former were some sort of subtitle to the latter.

If you see this movie anywhere other than on this Criterion DVD, you will see a movie that is 18 minutes shorter, and which, significantly, omits or truncates some of the most shocking images seen here. (You will also see much sparser and less accurate subtitling, Criterion wants you to know.) That version, the standard version, is in fact viewable online for free, beautifully restored in very high quality, here + here, courtesy of Mosfilm, which is pretty cool of them. However, having just sampled a few minutes I will note that the sound mix is noticeably different and there seem to be all sorts of tiny editorial alterations throughout; so despite seemingly being 95% the same, it manages to have quite a different “feel.” And the feel counts for much of what I got out of this movie.

The image quality on the Criterion disc, taken as it was from that “smuggled” print of the long version (possibly the only surviving copy?), is decidedly suboptimal, especially compared to the crisp restoration linked above. There is a murky, low-contrast fadedness to the black & white tones, and a general ghosting/halo effect. When it started I was afraid that the whole thing was going to be distractingly milky and thin. But as it turned out, the spirit-photograph quality of the image was entirely suitable to the soft, dreamy flow of the movie. Or at least it made itself into a compelling whole for me.

This movie is long. The “short” version is 186 minutes. The version that I watched is 204 minutes. Yes, The Ten Commandments and some other Hollywood monstrosities are longer than that, but this is surely the longest “art film” I’ve ever seen. Knowing what I was in for, I adopted a soft, accepting frame of mind and let myself drift without judgment. This turned out wonderfully and I recommend it. It may well be that all movies respond well to being viewed in a trance state, but this one seemed particularly to welcome and reward it.

The film exudes such composure and purity that it isn’t clear how it could have been actually made, given all the business and complexity that goes into shooting a film, which usually leaves a clear mark. The staging, camerawork, and acting almost never have that telltale aspect of cleverness and contrivance that feels like the essence of direction (and thus of moviemaking); here things seem just to be happening as they will, and yet beautifully. That’s the aspiration of many a humanist art film, of course, and I’ve certainly seen some that manage to avoid any sense of being calculated, but it’s almost always at the expense of basic cinematic appeal; such movies tend to be loose, limp, and give the impression only of having traded one kind of phoniness for another much less useful kind. Not so here. I don’t really know how he achieves it (well, art, taste, and skill is how) but Tarkovsky’s style is exactly what arthouse film should be: the material is poetic and open, but the staging and photography are endlessly crafty and compelling. And not in some arid, schematic, intellectual sense, but in a real, engaging, cinematically viable sense. The camera is almost always in motion, and all of the camera-movement devices — pans, zooms, tracking shots — have that inevitable, intuitive quality that gives them each their particular magical meanings. The style has a wonderful sense of flow, like a river of imagery.

I don’t know how much all that is just a description of the peaceful frame of mind I assumed while watching. I think “only somewhat.” A quote from Ingmar Bergman is included in the DVD liner:

My discovery of Tarkovsky’s first film was like a miracle. Suddenly I found myself standing at the door of a room, the keys to which, until then, had never been given to me. It was a room I had always wanted to enter and where he was moving freely and fully at ease. … Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.

That very much matches my sense of what I saw and encourages me that I didn’t simply zone out and then experience the movie as an aspect of that zone. But it is certainly in keeping with the zone: it is deeply unanxious filmmaking. It is “painterly” in the proper sense of the word, i.e. not meaning that it indulges in lavish decorative visuals, but rather that unlike most film, which draws primarily on the arts of the theater (and of the printed page), it genuinely draws on the visual and emotional language of painting. And incorporates the dimension of movement as an organic component of that language. There is movement in the frame so that there can be stillness in the mind. Or so.

This is all appropriate because the movie is ostensibly about a painter, though the action has very little to do with his painting, and often very little to do even with Andrei Rublev himself. The film is episodic and oblique and philosophical. It leaps around in time and place. It is broadly about life. I was reminded of Tree of Life, and of what else I’ve seen of Terence Malick. Obviously the influence goes the other way there. Whereas despite Bergman’s quote about Tarkovsky’s influence on him, The Seventh Seal, to which Andrei Rublev bears family resemblance in several aspects, precedes it by 9 years. Also, the emphasis on very long takes of the camera gliding dreamily through space reminded me, of all things, of Terry Gilliam. That uber-grandiose pullback shot from Baron Munchhausen that I’ve mentioned before is, I now see, the wacky comic-book descendant of several equally spectacular shots here. Unlike most philosophical arty films, the scale here is often very grand, with a horde of warriors on horseback, or shots that take in acres of landscape filled with hundreds of well-placed figures.

The movie ends with exactly the same gesture that I found affecting in the novel of Doctor Zhivago. For many reasons it’s even more affecting here, especially if you’ve been lulled into a state of dreamy receptivity and thus emotional openness, as I had been. After 3 hours you probably will be.

(The content of this movie, mind you, is not itself soothing. There is some really horrific medieval cruelty, culminating in a central long sequence of a town being sacked and people being tortured and slaughtered. There are also a couple of hard-to-watch shots of animal cruelty, some of which are apparently simulated, but one of which is most definitely the real suffering and death of a horse (confirmed on Wikipedia!). That’s hard, shocking stuff.)

Basically, this was high art and I welcomed it. It is made with a very deep intuition for the medium, luxurious to watch. It is tonal and the tone it sustains is a very worthy one. If it has a message, I would say the message is “Life is much bigger than good and evil, kindness and cruelty; so should art be. So do what you can do.” A good message. Also, understand that it does not have a message. It is a piece of art made to be reflected upon.

The film has a very fine score by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov, as sensitive and essentially cinematic as the camera style. The score is used sparsely and to excellent effect; whenever it is present it is lovely and well-judged. It only really breaks out at the end: the finale that I alluded to a moment ago is accompanied by a big extended piece for chorus and orchestra. It stands alone and is by far the most musically ambitious piece in the score, so I think it has to be my selection. I was a little reluctant about this choice because it’s almost a spoiler to hear this, the catharsis, without earning it over the course of the movie. But I don’t think spoilers can apply here; heard out of context I certainly don’t think anything is actually “spoiled.” This track is also longer than all our other selections, but that seems appropriate since this is the longest movie yet. (Oh no wait, Seven Samurai was longer. Well, that had a long musical selection too.)

So here is the Finale, our track 34. The transcendental 2001-like effect should be apparent. This is a movie that is about big things and this is the revelatory sound of big things. (As heard on this wobbly old print.) It is, I think, worth taking a moment to note how well this is achieved here and then to reflect on the dreadful ineptitude with which the “epic” effect is attempted in offensive caricature by every stupid comic-book movie score of the present day.

The disc has some intelligent quasi-scholarly commentary, but only on selected scenes, which is a little annoying to have to search and find. It also has some clips from interviews with Tarkovsky, which are very good.

I very much look forward to more Tarkovsky. Criterion’s not going to come through for me until #164, but on my own authority I might well resort to Mosfilm’s youtube selection, where several others are available.

Sorry this entry was long and dull. Sometimes they come out that way. And the work necessary to now make it short and dull does not appeal to me.

APOLOGY NOT ACCEPTED.

p.s. Your opinions are never dull.