Thomas Keneally (b. 1935)

The Playmaker (1987)

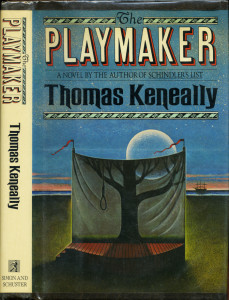

2084: The Playmaker, the first-listed (though second-written) of two selections by the Australian novelist Thomas Keneally, the other being his calling-card work, Schindler’s List (original Australian title Schindler’s Ark, 1982). Library copy of the American first edition, from the closed stacks.

This reading assignment happened to fall during a time when I’ve been actively trying to get my right and left brain to renegotiate some of their basic arrangements — a strange process and one still ongoing — and in trying to write it up I have found myself struggling to do justice to the essential bihemisphericity of my response. (This is my third attempt at writing this entry.) So this time we’re trying a new gimmick. Take it away, boys.

R: The Playmaker sounded dull and unpromising when I first read what it was (a fact-based novel about the staging of the first play ever performed in Australia, by penal colony prisoners in 1789) because I distrust historical fiction — it’s usually boring and misguided — and I especially distrust regional fiction. If you’re in a bookstore on Cape Cod and they’ve got a bunch of a locally-published mystery novels about Cape Cod (likely featuring cats and/or ghosts), you definitely don’t buy and read them. So ditto Australia, am I right?

But all the same, in my excitable innocent way, I harbored the hope that this would turn out to be some kind of hidden gem that I could recommend to people. The magic random wheel had spun me a modern but forgotten novel by a writer widely heard of but not widely read. Wouldn’t that be great, if it was great?

When the library called it up from the closed stacks (always a dramatic moment!), I felt like the jacket (as well as the dimensions, the heft of the book) was encouraging. It looked and felt appealingly like a book that was great in 1987 and then unfairly forgotten by cruel fashion. I had good times with library books of similar charisma in 1987; maybe this would offer suchlike good times! Look at that type design! Look at that weird, oh-so-book-cover-y bargain-basement-Magritte painting!

Even the interior offered coy charms: the title page is made to look like it’s printed on a curling theatrical poster, and then you turn the page and see the same poster again but now advertising the play to be performed by the prisoners. Then more novelty frontmatter: a “dramatis personae” and a list of “The Players” enumerating all of their crimes and sentences. Dull to read, admittedly. But I, R, can’t help but get excited about gimmickry. God help me I’d probably be reading Marisha Pessl or some shit if it wasn’t for the old ball-and-chain L. I love me some toys.

But there the toys ended, more or less. (Unless you count the weird two-page prologue(?) that follows, about which more later.) The novel proper started and suddenly it was exactly the book I feared, a boring and misguided historical novel about things I don’t care about, and one that failed to show me how or why to care about them.

Still, I reminded myself: I, R, am kind of timid and ignorant by nature and tend to have a sour-grapes response to everything foreign at first, until suddenly it seduces me. Lots of people love historical fiction. Maybe I just need to stick around and I’ll get drawn in by some kind of unforeseeable magic. Stories about staging plays are usually fun, after all.

But it wasn’t, and wasn’t, and wasn’t, and I truly had no interest in it other than holding it physically, and I had to force myself to go through with reading it. And then as I neared the end, I realized that I kind of had finally developed a faint but real interest in it.

It wasn’t that I found it appealing, exactly. It was sort of the thing I warned myself when reviewing a bad video game years ago on this site. I quote my younger self: “And yet, and yet, every game has its ‘thing going on.'”

This was a book, I’d been reading it, and at some point, the space within me where this book took place had been revisited often enough to have its own discernible flavor. I started to have spontaneous impressionistic thoughts about the subject matter. Huh, I thought, there is something sort of fascinating about the tenor of life in a young but established colony, after the immediate challenges of the elements and the natives are no longer overwhelmingly pressing, and people have to face the subtler challenge of fleshing out their sense of prosaic existence, of normalcy. The challenge not of living in some alien environment, per se, but of feeling that one lives there. I can relate to the troubling quiet of that problem.

“Hey,” I thought, “that’s basically the point of the book, I think! And here I was sort of musing on it – not dutifully, but organically and with a feeling of wonder! (Albeit mild!) So I guess at some level this book was working on me after all!” But only faintly. Still, to be honest, when it ended, my initial dismay had yielded to that old standby, benign indifference. I felt game: sure, why not.

All reading is sort of pleasurable, even reading something I don’t really care about at all. So sue me, I just like holding books and looking at the words and finding out what they say. Yes, of course, sometimes it’s a lot better than just that, but when it’s just that, who am I to complain? I’m R and life is just a bowl of cherries!

L: Well, that’s sweet and all but let’s be clear. This book is a godawful dud, awkward and tone-deaf and mismanaged every which-way. It is glaringly unworthy of inclusion in Harold Bloom’s list and is, I would say, the most thoroughly unrewarding of the 30-odd selections that “The Western Canon” has dished up for me. (Ezra Pound was a big drag too, but at least at the end I could say I read Ezra Pound, right? I read The Playmaker and all I got was this stupid T-shirt!)

The writing is such a dreadful performance of telling rather than showing that I often felt I was reading not a novel itself but someone’s rambling recounting of the events in a novel: “and then, and then.” Synopsis at 1:1 scale, the way an IMDB review might be written by an enthusiastic shut-in.

The author simply has no knack for prose. My sense was that he is probably a nice, enthusiastic, earnest person with a weak sense of humor and a weak sense of himself. At times I felt the uneasy embarrassment one feels in the presence of people entirely unqualified for their jobs. Even if one accepts “graceless delivery of information” as his style, the scheme of that delivery is itself often ill-calculated. The salient data for each lifeless character are re-stated over and over and over, as though assuming an amnesiac reader. The occasional clumsy gesture toward writerly panache, the shift from pure gray to bruisy gray-purple, only throws the vast flatness into relief. Bas-relief. I would characterize the style as “hopeless dullardry.”

Keneally’s skills and apparent interests all seem to lie at the earliest and most private phase of a writer’s work: the research, the synthesis of multiple historical sources, the devising of a framework for grafting personal observation and quasi-narrative onto pure documentary. (He’s written a long string of these histories-as-novels; I think it’s all he does. The latest one just came out while I was reading this.) And I’m comfortable granting him that there is something basically respectable in the bones of the work that undergirds the book.

But the failure of style is so utter and insurmountable that it’s not at all clear how to account for Harold Bloom’s having included this book on his list, even rashly, seeing as his entire raison d’etre is aesthetic snobbery. Possibilities are: 1) he never read it but liked the sound of what it was about; 2) he read or saw the play that another writer adapted from it, which has the reputation of being a sturdy and viable work, and assumed the novel was the same; and/or 3) he is friends with Keneally somehow. Or 4) he just screwed up completely and confused it with some other book. I mean, I guess I have to consider the possibility that 5) Bloom would dispute what I’ve said here about the style. But in the face of the evidence I find that very hard to sustain.

One of the major things the book wants to get across is that being in Australia, in 1789, was like being on the moon — unthinkably far away from the known world. He gets this across, characteristically, by stating it outright, in passing, hundreds of times. I will now gather his epithets for Australia starting at the beginning of the book (p. 25) until we all get sick of it.

p. 25: “this new penal planet”

p. 27: “this vast reach of the universe”

p. 30: “this new earth”

p. 34: “this outermost penal station in the universe”

p. 35: “this far-off commonwealth and prison”

p. 41: “this new penal commonwealth”

p. 52: “this strange reach of the universe”

p. 52: “a miraculous reach of earth”

p. 52: “the new planet”

p. 53: “this particular new world”

That’s enough. He keeps up this pace and this degree of variation until the outermost reach of this 352-page book.

Now for a real excerpt, and your chance to judge for yourself. Let’s see if I can find a paragraph or two that seems to encapsulate things, without digging unfairly hard for something bad.

Okay here’s what I picked, the start of Chapter 8. This is utterly characteristic, and, I feel, more than fair to Keneally because this is a scene with a basic and immediately comprehensible appeal: We’re witnessing the very first read-through of the play by the all-convict amateur cast. Sounds potentially good, right? You might well have expectations for the comic way this scene could go, Bad News Bears style. Or then again you might have expectations about more serious and dramatic things a scene like this could reveal. Nope. Neither. It’s not that kind of story (i.e. one that works). It’s “history”! In the sense of “high school history textbook”: a list of things that happened, grayscale with occasional spot color sidebars courtesy of Corbis Images.

Let’s just jump in here in the middle – I’m not going to explain who everyone is because if you had read the book up to this point you might still have trouble remembering anyway. Which is no doubt why he feels it necessary to name and explain who everyone is every time they are mentioned.

Ralph was soon depressed, though. He had gone to such lengths to cosset everyone’s sensitivity in the matter of having Nancy Turner the Perjurer as Melinda. But reading her lines she showed a shyness she had not exhibited as a lying witness in Davy Collins’s courthouse. “Welcome to town, cousin Silvia,” she mumbled. The happy and arrogantly artistic state the men’s performance had put him in now vanished. H.E. and Davy Collins would forgive him for using Nancy Turner the Perjurer if she were a dazzling Melinda. Those frightful Scots, Major Robbie Ross, H.E.’s deputy in government and commander of the Marine garrison, and his crony Jemmy Campbell, might even be appeased. But they would blame Ralph if Turner were poor, and their blame would be of the furious variety.

But his sweet, composed thief, Mary Brenham, saved the balance of his hopes by expanding before his eyes into Silvia, the way Arscott had expanded into Kite. It was the mystery again. It was the word made flesh. She took fire at the lines: “I need no salt for my stomach, no hartshorn for my head, nor wash for my complexion; I can gallop all the morning after the hunting horn and all the evening after a fiddle. In short, I can do everything with my father, but drink and shoot flying; and I am sure I can do everything my mother could, were I put to the trial.”

At “put to the trial,” she thrust her right thigh forward mannishly. It was sublime. Gardening could not match this, unless the turnips spoke back to you in the tongues of angels!

Huh? What the hell is this? Are you kidding me?

No. Nobody is kidding you. Not unless the turnips are speaking back to you in the tongues of comedians. Ho ho ho.

R: Shrug.

So, like I said, I was going to tell you about that two-page prologue.

Floating between the frontmatter and chapter one there’s this enigmatic, non-chronological, in media res prologue. It has no heading or anything to explain in what spirit it’s to be read. The main character of the book is Ralph, and the prologue starts with “First Ralph heard again how…” and then we have a sort of anecdote recounted, involving several other characters, but not Ralph. “First” before what? we wonder. Why is this scene special? we wonder. When will we understand? we wonder.

We understand on page 276, because the entire passage is repeated, but now completely in context, where it makes sense. Something is about to be told to Ralph by his ailing friend, but first Ralph hears again… this anecdote. A-ha! we think. Now what was enigmatic is meaningful. I have been drawn into the circle; I have met these characters and I understand the dynamics. I have earned this understanding and this familiarity, and now I comprehend the pall of pathos that hangs over this story. It all fits together. Things had all happened as they must. Fate. Something.

This came at around the point in the book where I was realizing that I was getting something out of it after all, and it fit nicely with that. I think I’d encountered this device of a premonitory repeated passage before, but usually in more fantastical writing. Here it took me by surprise and charmed me. It was pretty much one of my favorite things about reading this otherwise bland book.

Then later, when L was trying to find old reviews of the book online, we came across this. Pretty good punchline!

There’s probably some kind of lesson about art in there.

Broomlet.com super-fan “Maddie from Minnesota” contacted to our offices some time ago, asking humbly if she might be allowed to join the Western Canon Book Club of The Damned as a Junior Canonette. When this selection came up, I extended that opportunity to her, and, tragically, she took it. Upon completing The Playmaker she sent me some rather L-ish comments and invited me to include them in the entry proper, but I think it would better to let her express herself below. Especially now that she’s read all this text I just wrote.

Over to you, Maddie!