Stevie Smith (1902-1971) [born Florence Margaret Smith]

Collected Poems (1975)

[The new backend doesn’t offer me the ability to freely resize the thumbnails, which is why these are a little bigger than earlier ones.]

1578 is Stevie Smith, who is represented by one entry on the list: Collected Poems.

The attractive New Directions edition, on the left, came from the library, but once it became apparent that this was to be a long haul, entailing many renewals, I went in search of a purchasable copy, and lo and behold found the UK Penguin edition above, used, which under the cover turns out to be exactly the same book in every way.

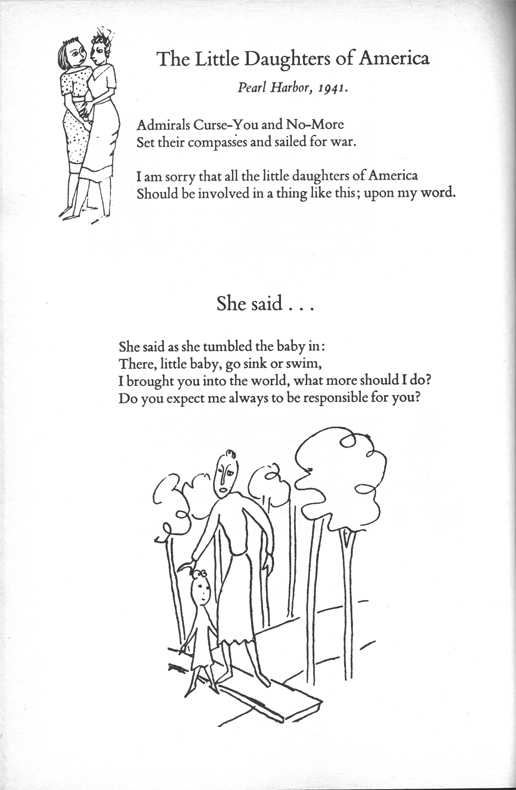

That being a book of 591 pages and nearly as many poems, most of them extremely brief, with very casual cartoon drawings sprinkled in the empty spaces on nearly every page. Some of them relate fancifully to the content of the poems; many simply do not.

Here is an arbitrary page to give you a sense. Imagine more or less this x 600.

What sort of a thing is this?

The Thurber-ish doodles contribute to an impression: that certain wit of not straining to be witty, perhaps not even being witty enough, because one is too splendidly content. Like what The New Yorker once was, an extreme dryness of pleasure that attests (by omission) to a wonderfully wet world. (Not actual dryness of course, but mock-dryness, ostentatious restraint to accentuate inalienable wealth of spirit.)

And some of it certainly partakes of that. But it is also something simpler: just some doodles. And just some poems.

I enjoyed reading Ammons because it was a psychological record. So too Thomas, though a grimmer one. And so too this. Complete collections of poetry feel more like something that was done rather than something that was made; a byproduct rather than a product. These words on the page are here because of certain moments in time, moments in which an individual was making a case for his/her spiritual legitimacy and personhood. The poetry is a residue of the function of the psyche that testifies “I am full and real.”

It is celebrated that Stevie Smith’s fullness and realness was eccentric, distinctive. To quote from the back cover: “… wholly individual… idiosyncratic … weird … new … bizarre …” But the more I shaded toward what seemed to me the spirit of the work itself, the more I felt that she was interested in her thoughts not because she considered her mind (or her self) thrillingly quirky, but simply and honestly because they were her thoughts. To me this was utterly sympathetic, and not particularly eccentric. Isn’t it rather worthless, as a critique, to note that something is eccentric – essentially, that it is different from the things that it is not? Once the horizons of other possible writers faded from view (there were no other possible writers within the limits of this book) the notion of eccentricity became useless.

(Though I did find myself falling back on it when asked to describe what I was reading. I would like to hold myself to a finer standard of saying what I really feel, but I’m not always up to that challenge.)

I mean, compared with what we expect of poetry, yes, her style and spirit make her deeply eccentric… as a poet. But as a person how eccentric is this, really? And what is a poet if not a person?

She certainly has recurring preoccupations (death, loneliness, the English, pets, fables and fairy tales) and in many of the poems has definite things to say. But for me the strongest impression was left not by the things thought or said but by the ease in thinking them and commitment to saying them, whatever they might be. It is hard for me to imagine that she did much revision. Nothing gives the sense that it has been “worked” in the least. The impression is simply of a genuine personality flexing naturally, in the implicit faith that writing is no more and no less than this.

And is it? Well, self-fulfillingly enough, I am grateful to have been in the company of exactly this, a deep self-trust, at least so far as this function of poem-making goes. It is contagious. Yes, we come to feel, of course it is good that she should write these things. It is good for her that she should write them, and it is good for me to be in the company of someone doing things that are good for her. This may have been a morbid life but it was also, it seems clear, a smooth one. The quality and character of that smoothness seemed like highly valuable instruction.

The first notes I jotted down last year about my reaction were that her style was characterized by “laziness, but a sort of salutary laziness.” In retrospect that sounds like a symptom of philosophical confusion. Stevie has helped clear up some of it. There is nothing “lazy” about writing many hundreds of poems.

[I thought and wrote similarly ambivalent things after reading Beckett. There has always been something simultaneously inspiring and intimidating to me about the profound composure, the lack of anxiety or “propriety,” in the way such writers take overt and unapologetic pleasure in being themselves, thinking their thoughts, and writing what they will. With Beckett I felt – and I still feel even in this moment – an urge to describe it as an “elitist” or “pseudo-aristocratic” mien, but where is that notion coming from? Not a part of me that is helping me. I must reject it. What such people exhibit is simply well-being and self-respect. To resentfully call it decadence is to consign oneself to the ghetto of the soul.]

[For a Stevie Smith example, listen and consider the following bagatelle of condescension: The Celts. Rather than taking some sort of imaginary offense, I would prefer to recognize that this is simply one woman being sincere and taking obvious pleasure in her sincerity. Listen to the joy in her voice as she says such things! How enviable!]

In the end I come away mainly with a sense of emotional texture and space, just as one comes away from visiting another household with a sense of its particular spiritual premises. Stevie Smith’s poetry and R.S. Thomas’s poetry and A.R. Ammons’ poetry really have nothing at all in common, but living with them has had in common that all were social experiences, a visit of the soul to someone else’s home. One samples the special valences of all their unspoken things: the weight of the rugs, the depth of the brown of the bookcase, the edges where two wallpaper patterns meet, the puddles of darkness left by the arrangement of lamps, the particular curlicues on the ends of their silverware. Smells deep in the furniture, that these people live inside and will never quite smell.

The cover of the Penguin edition up there gets right to the point. Look at where we’re visiting! A sitting room both strange and lovely and sad and spooky and ordinary and perhaps a bit tiresome too. But very real and lived, which is the charm that goes beyond charm. I have benefited from her room being so real, even while I didn’t know what to make of a lot of her decor. But after all it’s not for us, it’s for her; we’re just guests.

I will say this about reading complete corpora: it takes a long time. I thought at first that since the poems were all so short and whimsical I could just breeze through this book, but that was naive. Really getting to know someone takes a while; there is no quick way about it. In this project, 2008 was the year of Edgar Allan Poe. 2011-12 was the year of R.S. Thomas. 2012-13 has now been the year of Stevie Smith.

The next time I roll something like “Complete Poetry,” I may decide to make a special new dispensation to roll again for a second selection to read concurrently. Poetry needs to be read in parallel with other things; it insists on gaps.

Anyway, we’ll have to wait see about that, because that isn’t what happened this time around.

Examples for you.

First of all, you can hear several more readings on soundcloud, including this one, of her most famous poem, with a fine general self-introduction that basically jibes with my impressions above; and this goofy one.

A good majority of the poems could be considered self-portrait, in some degree. I’ve chosen this one to represent her because the morbid strain is much more subdued than elsewhere and thus easier to wrap one’s heart around. Not to say that that’s our responsibility.

In My Dreams

In my dreams I am always saying goodbye and riding away,

Whither and why I know not nor do I care.

And the parting is sweet and the parting over is sweeter,

And sweetest of all is the night and the rushing air.In my dreams they are always waving their hands and saying goodbye,

And they give me the stirrup cup and I smile as I drink,

I am glad the journey is set, I am glad I am going,

I am glad, I am glad, that my friends don’t know what I think.

And to wrap things up, here’s one for Harold Bloom, from whose shadow this project takes its silhouette if not exactly its spirit, and who chose this book for his list despite its having this poem in it. Though who knows if he’s ever read it.

Souvenir de Monsieur Poop

I am the self-appointed guardian of English literature,

I believe tremendously in the significance of age;

I believe that a writer is wise at 50,

Ten years wiser at 60, at 70 a sage.

I believe that juniors are lively, to be encouraged with discretion and snubbed,

I believe also that they are bouncing, communistic, ill mannered and, of course, young.

But I never define what I mean by youth

Because the word undefined is more useful for general purposes of abuse.

I believe that literature is a school where only those who apply themselves diligently to their tasks acquire merit.

And only they after the passage of a good many years (see above).

But then I am an old fogey.

I always write more in sorrow than in anger.

I am, after all, devoted to Shakespeare, Milton,

And, coming to our own times,

Of course

Housman.

I have never been known to say a word against the established classics,

I am in fact devoted to the established classics.

In the service of literature I believe absolutely in the principle of division;

I divide into age groups and also into schools.

This is in keeping with my scholastic mind, and enables me to trounce

Not only youth

(Which might be thought intellectually frivolous by pedants) but also periodical tendencies,

To ventilate, in a word, my own political and moral philosophy.

(When I say that I am an old fogey, I am, of course, joking.)

English Literature, as I see it, requires to be defended

By a person of integrity and essential good humour

Against the forces of fanaticism, idiosyncrasy and anarchy.

I perfectly apprehend the perilous nature of my convictions

And I am prepared to go to the stake

For Shakespeare, Milton,

And, coming to our own times,

Of course

Housman.

I cannot say more than that, can I?

And I do not deem it advisable, in the interests of the editor to whom I am spatially contracted,

To say less.

You know, I thought I was going to end it there but I just came across this Believer article on Stevie Smith by David Orr, and now I have a couple last musings about Monsieur Poop.

The Believer article is basically in agreement with me about what we might get from Stevie Smith. But there is something frustrating to me about the fact that Orr sees no alternative but to write it in a way that does not get that very thing. His language of appreciation has to work and work and work its way to being able to articulate that Stevie Smith’s lack of workedness is valuable. If he had really found his way to it, wouldn’t he have taken it to heart?

Plainspoken sincerity is made of win! Best. Way. Of Communicating. Ever.

(I see what you did there.)

Yeah, I know, my little joke is pretty far off to one side – “plainspoken sincerity” does not describe Stevie Smith, and Orr’s hypocrisy is obviously a different one. But the principle is the same. (Anyway, letting my joke veer way off to one side is just me letting myself be. WWSSD?)

Here’s what I’m saying, and I think what Stevie was saying about Monsieur Poop. Most critical writing is inherently defensive, such that it doesn’t actually touch what it embraces. Harold Bloom ostensibly embraces Stevie Smith because here she is on his list of worthy works. But he clearly, in word and deed, does not embrace what she stands for and believes in. So what sort of embrace is it? And who really needs that kind of embrace when you can have the real kind?

And if you are writing criticism exactly because you can’t have the real kind of embrace, because you’ve gotten too uptight, why would you chose to write criticism at all? To try to keep alive something authentic you remember from your youth? How dreadfully sad.

Is it possible to be truly touched by something that you don’t dare to resemble? I don’t think it is.