11] Blumenfeld: Four pieces, op. 2 (1883–5)

(Ф. Блуменфельд : Четыре пьесы : для фортепиано : соч. 2.)

Quatre morceaux : pour Piano : composés par : Félix Blumenfeld. : Op. 2.

[Four pieces: for piano : composed by : Felix Blumenfeld : Op. 2.]

1. Etude (A dur)

2. Souvenir douloureux

3. Quasi Mazurka

4. Mazurka de Concert

• 29 Quatre morceaux, op. 2 (1886)

• 612–615 (= the individual pieces from within 29, made available separately around 1892)

Sibley scanned their copy of this opus in 2005, and that’s what appears at IMSLP, but it’s not ideal for my obsessive purposes, because it consists of separate issues of nos. 1, 3, and 4 (which lack the original title page), and a Carl Fischer edition of no. 2, edited and fingered and completely reengraved.

But we’re in luck: a copy of the entire original Belaieff 29 was uploaded to Pianophilia in 2010 by “Alfor,” who also provided a color scan of the title page:

Felix Blumenfeld (1863–1931) was a pretty major pianist-conductor-composer-teacher, quite well known among the piano superbuff crowd that hangs out at Pianophilia, but not so much by anyone else. If I (or you!) continue this journey through the Belaieff catalogue, you’ll be hearing a lot more from him (and his brother). Here in 1886 he’s 23 years old, just emerged from Rimsky-Korsakov’s tutelage at the conservatory, and getting four of his more recent little piano pieces published, arbitrarily grouped (it would seem) as Opus 2. (Blumenfeld’s Opus 1 is 6 songs, of unknown date, which Belaieff didn’t publish until 1900. Presumably there was a earlier first edition from some other publisher.)

1. Etude (1883)

A ma mère.

This is 2 minutes long, and has been recorded exactly once, by Daniel Blumenthal (a fellow Blumen) in 1993. It’s musically slight, but not vapid; it has confidence and taste and is sure-footedly pianistic. It has more brillante octave virtuosity than I’m personally comfortable with, but I can fake it. There’s a good early use of the Rachmaninoff hand-alternation melody-in-the-thumbs gimmick on the second page. I think it’s early, anyway; I don’t think Liszt ever quite did that one. And I like the coda (that takes up more than a third of the piece) where things unexpectedly get a little crepuscular. They didn’t have to! He just decided to! I appreciate that kind of choice, especially in a piece that is otherwise squarely about flash.

2. Souvenir douloureux (1885)

[= Painful Memory]

A ma soeur Olga.

About 3.5 minutes long. It has been commercially recorded once, by Jouni Somero in 2003, but the recording doesn’t seem to be freely streamable at present. However on Youtube you can listen to a recital performance by one Luisa Splett.

This is very similar in texture and attitude to the Grieg Lyric Pieces: a simple idea put through some simple but pregnant harmonic changes, and then repeated. Unlike most of Grieg, there then follows a coda with a genuine culmination, which retrospectively makes the preceding repetition seem tedious.

(At least to me. I can either do a fundamentally static circular paradigm or a narrative developing one. This is also why I often have trouble with Schubert, who likes to repeat things a lot but still eventually end somewhere that “reflects” on the preceding journey. I feel weird about reflecting having gone in loops. Maybe that’s something to get over.)

(Sonata form might seem to be circular, especially when repeat signs are observed, but to my mind the essence of sonata form is that it is fundamentally linear, forward-moving, and incorporates the experience of recurrence within that forward motion. The use of repeat signs in sonatas bears this out: they never repeat the vital transition from beginning to ending; they repeat just the departure at the beginning (which is different the second time because it’s no longer really a departure) and then they repeat just the arrival at the ending (which is different the second time because only then is it really an ending.) Whereas Grieg’s little pieces really do happen twice in their entirety.)

The real problem with this piece is that it never quite convinces me that it has a melody; the harmonies are pleasant but the scale-walking is a little too unbroken to hold my attention. I wonder if it’s about an actual painful memory of his. Maybe his sister Olga knew what he was talking about.

3. Quasi Mazurka (1885)

A ma soeur Jeanne.

This piece has never been recorded! The first of many.

Why not? No good reason. There’s nothing wrong with this piece. The first theme is appealingly sunny, and then elegantly lets minor show through, in the middle section, without the beat changing a bit. Having no ritards or rubato at all gives an impression of sincerity that holds my attention.

I guess Chopin and Polishness in general were in fashion in Russia; there are gonna be a ton of Mazurkas (and quasi-Mazurkas) to come.

Here’s me, whacking my way through it.

This is from a few years ago when I happened to record myself playing it at a real piano. On this recording I was playing so much slower than prescribed by the composer that I’ve decided to present it here digitally sped up 25% (pitch-corrected, of course) in the hopes of giving a slightly closer impression of “the piece itself.” This is just a practical measure; I’m not trying to trick anybody. Also, for the most part this is still quite a bit slower than marked in the score. At tempo it would come in at more like 3 minutes, I think.

After 3 pieces I’d say that Felix Blumenfeld likes expressive codas.

4. Mazurka de Concert (1885)

A ma soeur Marie.

This piece has never been recorded either! Why not? Also no good reason. The main theme is hummable, if perhaps not quite catchy, and Blumenfeld’s pianistic writing continues to be of a very high quality. The warm B theme, in triads over a drone bass, is very attractive, and then returns to great effect in yet another expressive coda, this time the sort with a wistful diminuendo followed by a ringing, triumphant stringendo. Satisfying!

Again, until some record label steps up to the plate, all I can offer you is this sloppy readthrough from me.

Even more wrong notes this time, because it’s harder. This comes from that same day as the previous, and this too has been sped up 25%, which still isn’t nearly as fast as the composer asks. (But speeding it up any more will make it sound too unnatural, I think.) Imagine the whole thing breezing along tunefully and lasting around 4 minutes.

12] Kopylov: Two Mazurkas, op. 3

(А. Копылов : Две мазурки : для фортепьяно : соч. 3.)

Deux Mazurkas : pour le Piano : composées par : A. Kopylow.

[Two Mazurkas : for piano : composed by : A. Kopylov.]

No. 1. en Mi mineur, dédiée à Mr. A. Reichhardt.

No. 2. en Sol mineur, dédiée à Mr. N. Rimsky-Korsakow.

• 30 Deux mazurkas, op. 2 (1886)

• 621–622 (= the individual pieces from within 30, made available separately around 1892)

30 was scanned by Sibley in 2007.

From the prices, the color, the lack of a date, and the reference to Büttner, this would seem to be an 1886 original.

Okay, now we’re getting into the real obscurities. That’s what I’m here for! Alexander Kopylov (1854–1911), on the teaching staff at the Imperial Chapel, and composer of secular works in his free time. A private student of Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov in the 1870s, and then a member of the Belaieff circle. Not completely unrecorded — three orchestral works and a couple of choruses are available in one recording each, plus his contributions to some collaborative works. But he wrote at least 60 opuses, so that’s not very much.

Danny Kaye says his name at 2:49 so you know he’s for real.

He was 32 when these mazurkas were published; we don’t know when they were written. Both are unrecorded (as I mentioned a few entries ago).

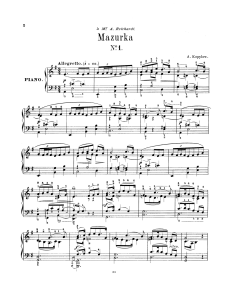

No. 1. en Mi mineur, dédiée à Mr. A. Reichhardt.

I have no idea who Mr. A. Reichhardt might have been; maybe someone at the Imperial Chapel. The mazurka dedicated to him is very lovely, though. Sweet and gently sentimental, with a poignant major-minor slide in the very first bar that remains effective even after it’s been heard 12 times, never changing. To my mind, this is a first-rate melody, somewhere between naive and knowing, and I don’t get tired of it. Something about the way the first phrase drifts briefly upward into a simple major resolution in parallel 6ths is very potent for me. I don’t know why.

And then the rustic dance in the middle is a stirring change of scene. Even the standard Borodin falling chromatic tenor line feels sincere and fresh under the circumstances. All tastefully contained within a modest salon style.

That’s why I love these title pages so much — they really do look exactly like the music!

Here I am playing it.

This is a strange performance, from the same day as the Blumenfeld above, and similarly very slow, but this one I couldn’t speed up because the middle section is already up to tempo and it would become absurdly fast. So understand what you’re hearing: this is a weird sentimental-daydream rendition; the marked tempo is Allegretto and almost twice as fast. And all those pauses at the end are me indulging a whim, I guess; they’re not part of the piece. I’m not sure what was going through my head, but something, apparently.

This recording clocks in at 4:22. It should probably be more like 3:30! But you can at least hear how the tunes go.

No. 2. en Sol mineur, dédiée à Mr. N. Rimsky-Korsakow.

Mr. Rimsky-Korsakov we know. This is a natural sibling piece to the preceding; it has enough of its own character to stand apart, but the same basic outline: a melancholy major-falling-to-minor A section with brief tragic outbursts, and a heartier B section with a Borodin chorus. This one feels like the darker of the two — night has fallen pretty completely by the end. I like the way the main theme of this one sort of drips and sighs downhill, and then comes around to do it again, over and over. So far it seems like Kopylov had a good feeling for melodic contour. Far better than the Blumenfeld mazurkas above, which covered similar ground but with very different strengths.

These Kopylov pieces are intermediate or easier, whereas the Blumenfeld pieces all implied the need for advanced technique, even if it was mostly being held in reserve. I tend to admire easy pieces more than hard ones. Or perhaps I should say I admire pieces that feel like they were adapted to suit the inclinations of the hands rather than the other way around. (Of course, if I had better technique, in the Czerny sense, I might not be able to make any such distinction.)

Anyway, these two pieces by Kopylov are very gracious in the hands, by which I mean in my hands, which protest childishly when asked to play arpeggios. Do I mean “gracious” though? I think I do.

My iffy performance.

This has been sped up 19% (10% and then “10%” again… that’s 19%, right?) because it’s from that same day a few years ago, when apparently my heartbeat was nice and slooow. Once again I make some idiosyncratic sentimental choices as I near the end. I also make plenty of mistakes, including the very first harmony. Oops. Well, this is what there is.

I think at the proper speed this would come out to about 3 minutes.

13] Sokolov: Twelve Songs, op. 1 (texts by Nikitin) (1881–??)

(Н. А. Соколов : Романсы : на слова Никитина : соч. 1.)

(12 Mélodies : avec accompagnement de piano : par Nicolas Sokolow : Op. 1. : Paroles russes de Nikitine.)

[12 Songs : with piano accompaniment : by Nikolai Sokolov : Op. 1. : Russian words by Nikitin.]

Vol. I, for medium voice. “Version française de F.V. Dwelshauvers et A. de Gourghenbekoff.” (13 p.)

1. Певцу / Au poète

2. Дитяти / À l’enfant

3. Живая речь, живые звуки / Le bruit du monde (1881, 3 p.)

4. В темной чаще замолк соловей / Le rossignol s’est tû (1881, 3 p.)

Vol. II, for high voice. “Version française de Jules Ruelle.” (25 p.)

5. Когда закат прощальными лучами / Coucher de soleil (5 p.)

6. Засохшая береза / Le bouleau desséché (4 p.)

7. Молитва дитяти / Prière d’enfant (6 p.)

8. Мельница / Le moulin (8 p.)

Vol. III, for low voice. “Version française de Jules Ruelle.” (19 p.)

9. Дуб / Le chêne (4 p.)

10. Нищий / Le mendiant (3 p.)

11. Дедушка / Le grandpère (4 p.)

12. Мать и дочь / Mère et fille (6 p.)

• 31 Тетр. 1. для сред. голоса с сопровожд. фп. / Cahier I. Pour Mezzosoprano ou Baryton. (1886)

• 32 Тетр. 2. для выс. голоса с сопровожд. фп. / Cahier II. Pour Soprano ou Ténor. (1886)

• 33 Тетр. 3. для низ. голоса в сопровожд. фп. / Cahier III. Pour Basse. (1886)

• 398–409 (= the individual songs from within 31–33, made available separately around 1891)

As you can see, I’ve got nothing. The images aren’t available, the scores aren’t available, the songs have never been recorded. All I can offer you is:

1) A 1994 reprint of volume 2 (by obscure-song specialty publisher “Recital Publications, Huntsville TX”) was scanned by Google for the University of Michigan and, though it can’t be browsed at all by the general public, a very tiny thumbnail of its cover can be viewed. But of course Recital Publications replaces a lot of the text on their reprint covers, usually only retaining the upper half of the original title pages. Here you can just make out the type design of the word “Mélodies,” and that’s about it.

2) You can read most of the Russian texts of the songs, and see the first lines of the French texts, here.

As to what this work is like, all we can do is speculate.

Nikolai Sokolov (1859–1922), the man who rhymes with “Kopylov” in Danny Kaye’s song, was 27 years old and one year out of Conservatory (having studied under Rimsky-Korsakov) in 1886, when these were published (though the two songs whose dates are available were written in 1881, when he was 22 and still a student). Like Kopylov, he was teaching at the Imperial Chapel, though later, unlike Kopylov, he’d be hired by the Conservatory. Solo songs proved to be a recurring interest; he’ll be back again later in the catalog with some music we can actually look at.

Ivan Nikitin (1824–1861) was, from what I’ve read, a moderately well known, moderately respected, basically unexceptional poet from earlier in the century. His poetry was nonetheless set to music many times, disproportionately by members the Belaieff circle. From what I read of the lyrics, in manner and matter these are your standard 19th-century Lied texts: sentimental musings on nature images or human archetypes.

Sokolov seems to have been the first of the bunch to set Nikitin. At 12 songs to be performed by three singers, it seems like this is a rather substantial and ambitious cycle. But without hearing (or seeing) the music, it’s very hard to say. It might just be a bundle of student works, organized this way for the publisher’s convenience.

[If you’re really curious, I think your best bet is to pay the Bavarian State Library to make you a pdf from their copy; they have a convenient scan-on-demand service. 57 pages comes to $28.]

14] Sokolov: Three Songs, op. 2 (texts by Kozlov, after Musset) (1885)

(Н. А. Соколов : Романсы : на слова Козлова (из Альфреда де Мюссе) : для голоса в сопровожд. фп : соч. 2.)

(3 Mélodies : pour chant et piano : Op. 2 : par N. Sokolow. : Paroles russes de Kosloff d’après Alfred de Musset. : Traduction française de Jules Ruelle.)

[3 Songs : for voice and piano : Op. 2 : by N. Sokolov. : Russian words by Kozlov after Alfred de Musset. : French translation by Jules Ruelle.] (21 pp.)

1. Вечерняя звезда / L’étoile du soir (7 p.)

2. Надежда / Espérance (4 p.)

3. Бедняк и поэт / Le pauvre et le poète (8 p.)

• 34 Trois mélodies, op. 2 (1886)

• 410–412 (= the individual songs from within 34, made available separately around 1891)

Same deal. No score, so recording, no pictures. Ivan Kozlov (1779–1840) was another middle-tier sentimentalist poet of a few generations past; Alfred de Musset (1810–1857) is somewhat better known, though perhaps Russians would disagree.

After no small amount of labor on my part (why? why?) I have determined that all three texts are selections from Kozlov’s version of Musset’s long poem Le Saule (1830). But Kozlov’s translation is so exceedingly free that I’m not sure the second selection here even has a directly corresponding passage in the original. (The French in the score of course is not original Musset but a singable back-translation by Mr. Jules Ruelle.) All quite melodramatic and unremarkable stuff, by the looks of it, which isn’t to say it might not also be beautiful and worthwhile, or at least make for pretty songs. Who knows?

[Bavaria can get you this one too, if you need it.]

15] Shcherbachov: Mosaïque (Mosaic), op. 15 (1885)

(Н. В. Щербачев : Мозаика : соч. 15.)

Mosaïque. : Album pittoresque. : Morceaux détachés : pour Piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 15.)

[Mosaic. : Picturesque album. : Miscellaneous pieces : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 15.]

No.1. Rêverie-Prélude

No.2. Orientale

No.3. Elégie

No.4. Guitare

No.5. Valse-Intermezzo

No.6. Pervenche

No.7. Marionnettes

• 35 Mosaïque, op. 15 (1886)

• 350–356 (= the individual pieces from within 35, made available separately around 1891)

35 is available in a scan from RSL as linked above, which can also be found slightly cleaned up at IMSLP. (There’s a second scan at Pianophilia from a slightly later copy.) The excellent color title page comes from the Beattie collection.

Here’s some fairly mauve prose on Mr. Nikolai Shcherbachov (2:57), and on this opus in particular, from the American critic Philip Hale (and, quoted, his colleague James Huneker), writing in 1900:

Prominent among the writers of piano music is Nicolas de Stcherbatcheff. who was born August 24, 1853, and distinguished among his works are collections entitled “Féeries et Pantomimes” (Op. 8); “Mosaïque” (Op. 15); “Zigzags” and “Les Solitudes.” “Mosaïque” is made up of “A Revery Prelude”; “An Orientale” of bewitching beauty; a pathetic elegy; “Guitar,” a strange number in which there is a serenade in a cemetery; a waltz that is brain-maddening; “Periwinkle”; and “Marionettes.” His music is baffling at first to the reader; there are unfamiliar harmonic progressions; there is shifting or unusual rhythm; there is unaccustomed melody; in a word, the music is exotic. But to the musician of temperament, soul, imagination, a new and beautiful world is opened, and he escapes for a time from commercial music and bargain counterpoint. He knows the full passion of a summer evening, and why moonlight is so feared by the prudent. He realizes that the waltz which is danced only in the bewildered mind is more intoxicating than that to which conventionally shod feet keep time.

Mr. James Huneker has finely characterized this strange composer: “Stcherbatcheff is a musical Gogol who would create another ‘Taras Bulba’ if he dared, yet contents himself writing small dangerous things for the piano. Who eats of his music is made mad, as are the devourers of mandrake. Bitter-sweet is it with rhythms that lull you and poison you. A valse of his that I tasted made my brain whirl. In my arms I held a bewitching creature, with a false red mouth, and our dance was vertiginous. Chromatic nightmares murdered our love, and then I knew that Stcherbatcheff is to be feared.”

This is of course quite over the top; I include it mostly because it serves as a reminder that it is possible to have strong and colorful feelings about a composer like Nikolai Shcherbachov (1853–1922), despite his being no more than a footnote in any conceivable history. It’s easy to slip into the error of believing that footnotes were born to be obscure, are intrinsically gray. Hopefully the overwritten stuff above will help counterbalance that impression.

The source from which that quote was taken (“Famous Composers and Their Works, Vol. I”) also includes a sketched portrait of Shcherbachov, the only one of which I’m aware.

Of the several extremely forgotten composers in the Belaieff stable, Shcherbachov does seem to me one of the least deserving of the fate. His many piano pieces are generally quite spirited and colorful and surely merit a few recordings here and there, rather than the absolutely none that they have received. Beginning with this cute and appealing little album. Sure, it’s no Pictures at an Exhibition but neither is it just piano bench trash. I don’t know about “exotic” or “dangerous,” but it’s all certainly good-humored and attractive. The mosaic doesn’t really add up to a bigger picture, but it’s a reasonable bundling of seven disparate pieces (“morceaux détachés”). I guess I thought to compare it to Pictures because as with Mussorgsky there is a kind of rough enthusiasm just below the surface that occasionally rises up and overrides “correctness.” Some of the pieces may seem a bit imbalanced at first, but they’re actually following their own subtly idiosyncratic ideas of balance.

This composer’s name can be transliterated many many ways. The basic points of variance are the initial complex consonant Щ, for which you might see any of “Shch,” “Stch,” “Tsch” “Schtsch”; the related but simpler consonant ч (“ch,” “tch,” “tsch”); the last vowel, which even in Russian sometimes appears as е and sometimes ё (“e,” “ye,” “o,” “yo”); and the final consonant в (“v” or “ff”). These possibilities don’t recombine completely freely, of course, but that’s still a lot of options. It definitely slows up catalog searches!

I’m using the spelling “Shcherbachov” because that’s what Grove uses — though they also slip and use Shcherbachyov with a Y at one point so how serious can they be?

1. Rêverie-Prélude

This first item is to me the oddest of the bunch: a meandering improvisation on a standard idyllic waterfall harp figure, clearly meant to be “perfumed” and “sensual.” But does it make “sense”? Maybe it doesn’t need to?

It is oddly hard to play — not only because it’s so freewheeling that it resists confident sightreading, but also because for some reason Shcherbachov has put counterintuitive details into nearly every bar, places where the arpeggiation becomes impure and sounds two notes at once. Despite being a bunch of standard swoons in a row, I think this piece might demand careful preparation.

Since none of these pieces have ever been professionally recorded, you’re definitely not going to get that. Instead you get this:

Since recording this very inaccurate and intentionless playthrough a few years ago, I have actually come to understand the piece better, but all I can record at present is on my clunky phony Casio keyboard, which is so much less pleasant to the ear (see below!) that for now we’re sticking with the above. (Yes, I sped it up 20%.)

Approximately 3 minutes.

2. Orientale

An American non-Belaieff edition of the Orientale was published in 1895, edited by Edward MacDowell, and at least into the 1910s the piece made occasional appearances in “100 Piano Classics”-type compilation volumes. It was almost going to be a “famous” piece, for a little while there. But things didn’t pan out that way.

It’s a sweet and simple little tune, the pentatonic orientality of which is mostly (but not completely) subsumed into the standard St. Petersburg harmonization, which creates a special gleam of innocence. Even if it is a bit greeting-card and commercial, I like it.

It can be heard played in-a-pinch serviceably by Youtube stalwart Phillip Sear, staring hard at the score in an attitude that is very familiar to me, though I don’t recommend it as a way of making good music.

Unfortunately the only time I recorded this piece at a piano, I misread the key of the middle section, so even for present purposes it’s not acceptable. Oh well.

Approximately 3 minutes.

3. Elégie

The B section is marked “come a due,” (=”like two”) which I take to mean “like a vocal duo.” This marking could just as well apply to the whole piece. It seems essentially to be an Italianate operatic love duet arranged for piano, with the slightly unpianistic effect that implies — the accompaniment is constantly getting mixed in awkwardly among the melody lines. As far as the tunes go, this is fairly generic stuff in a style that has never quite appealed to me; a little emotionally oversold. But there are a few nice turns. I’m not complaining.

Here I am banging it out clumsily on the klonky synthesizer without having gotten to know the piece very well. Listen to those plastic keys thud!

On further consideration, this probably wants to be a lot rhythmically steadier and more serene.

Approximately 3.5 minutes.

4. Guitare

There’s certainly plenty of strumming and plucking and flair from the outset, but I’m not sure the effect is quite guitar-like; it’s a bit too high in the treble for that. More like a mouse guitar. It’s cute, whatever it is. Then the interlude in the middle, identified as “Sérénade sur une tombe,” does a bit better at evoking guitars and Spain and moonlight and whatnot, though Shcherbachov can’t help himself but harmonize in the Russian chorale style.

All in all this may be my favorite in the opus — it’s like a cheesy engraving, executed with panache, which is exactly what it wants to be. The break-of-day effect of having the serenade theme return in major at the end is so wonderfully unnecessary that I find myself taking it seriously, being touched by it.

Particularly sloppy performance on the Casio. Sorry.

Approximately 6 minutes.

5. Valse-Intermezzo

Hale called this “brain-maddening,” which is a very hard adjective for me to hear in this gentle, sociable, feminine piece. Can the witty little misdirections in this harmless trifle possibly be what Huneker had in mind when he wrote all that gunk about “chromatic nightmares murdered our love”? Gosh, I hope not! Surely even a music critic in 1900 wasn’t that oversensitive. Perhaps the gothic, “vertiginous” waltz he had in mind will be identifiable in some Shcherbachov opus further down the road.

Once again, Shcherbachov gives a modest piece his full invention and consideration. No corner-cutting in this salon. In playing it one sees how much care has been lavished on this little confection. It’s more intricate than it sounds! But then again it’s also easier than it looks.

This one has a Phillip Sear Youtube rendition.

Approximately 2.5 minutes.

6. Pervenche

[= Periwinkle]

An unusual little “album leaf”-style character piece that reflects temperamentally on a very tiny, shortwinded idea. Like the opening Prelude, this has an underlying spirit of improvisation, though its surface is entirely composed and orderly. Very much in the vein of the Schumann Davidsbündlertänze — you can hear both Florestan and Eusebius in this one. I enjoy the poetic flourish at the end of the piece: it works itself up emotionally to a bare high note, hangs in silence for a very long time, and then just floats to the ground, spent and perhaps a bit abashed: the end.

I don’t know what it has to do with periwinkle, but that’s a fine name for a boutonniere piece like this. Why not. Like Schumann’s Papillons. Schumann is a good point of reference for most of the pieces in this set, isn’t he.

This is our third and final Phillip Sear performance.

Approximately 2.5 minutes.

7. Marionnettes

With its grandiose introduction, this one announces itself at the outset as the big finale of the opus… but that turns out to be sort of a joke. The piece is actually a tinkly puppet show. Or is the big buildup semi-serious after all? His intention seems to be the sincere glorification of tinkly puppet shows, which is to me a touching thing to attempt. It’s half-in-jest but there’s something very genuine about even the jest. Maybe I’m crazy but I detect a depth of feeling behind this piece. It’s implied by the combination of music-box childishness with Lisztian virtuosic sparkle; the feeling emerges faintly in the space between those two lines.

Me, playing the Casio Klonkenklavier:

That’s neither the notes nor the tempi, but it’s the closest thing you’re gonna get until you learn to play it yourself.

Approximately 5 minutes.

All in all, I find this Mosaïque to be a place worth returning. It’s an important part of my piano-playing life for there to be whole collections of pieces I can dip into that pose no emotional challenges, where everything being conveyed is basically positive, life-affirming, simple. This is a nicely varied such collection, and, within those terms, even a potentially deep one. The way fans of a pop album can find hidden depths in the interrelation and sequence of its songs, I can find it profitable to muse on the way “Guitare” does or doesn’t relate to “Marionnettes,” or the way the whole sequence does or doesn’t emerge from within the waterfall of the initial “Rêverie-Prélude.” Whether or not Shcherbachov conceived this set as an cycle (I suspect not), he assembled it into a real one, with its own internal life.

And what a great cover!

Next time, if a next time arrives, will be an all-Shcherbachov edition. So that we might continue to learn why moonlight is so feared by the prudent.