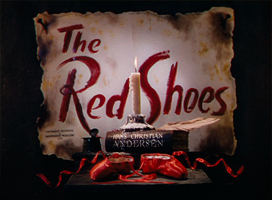

written and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

Criterion #44.

Not just any Red Shoes but The Red Shoes. My movie literacy has gone up one point.

I already said my bit about the reassuring embrace of Technicolor here, but this is obviously the better place for it. This is one of the most Technicolor movies ever made. The virtues and effects of this movie are exactly the virtues and effects of its palette; it is, like The Wizard of Oz or Fantasia, an incarnation of the spirit of Technicolor.

Much of that Technicolor worldview is nourishing to me, and makes me envy and admire the people of the past, whose heads were so naturally full of such simple, sturdy stuff. But those heads had other sorts of stuff in them too, older stuff, equally characteristic of their era but of no particular value to me. Some such stuff was in effect here. I refer in particular to operatic doom, which provides both the obsession and actual outcome of The Red Shoes. We’re on the same spiritual-aesthetic plane as Fantasia, but tilted downward; instead of a dreamy optimism, we get a dreamy fatalism. The movie’s trajectory of doom makes sense to me only as a well-worn formula; by the story logic there is no actual tragic necessity. And, to my mind, neither is there any tragic necessity in the aesthetic logic either, even though that is clearly the filmmakers’ intention.

“To my mind” is an important caveat in such matters.

Beth and I recently read (in this enjoyable anthology) Molly Haskell’s essay on “The Woman’s Film,” which I recommend. Haskell observes that the tear-jerking scenarios found in “weepies” offer wish-fulfillment fantasies that reveal their audiences’ psychologies… but they only offer wish-fulfillment in its most conservative form, which tends to perpetuate rather than alleviate the audience’s problems. Women who feel trapped by the constraints of their social roles find a validating outlet for their feelings in exaggerated cinematic images of those feelings, e.g. movies about grand women who make grandly painful sacrifices… but being gratified by images of the poignant nobility of suffering only reinforces the oppressive paradigm, in which being trapped is in fact inescapable, necessary, and right. People will pay to be reassured that their resentments are necessary; they will not pay to be shown a way out, because that will entail feeling shame. (My summary.) This is her feminist thesis and it’s a good one. I only summarize it here because I want to invoke the general principle, which lingered in my mind while coming to terms with The Red Shoes.

I don’t think the illogical doom of the ballerina in this movie is based on the exact same oppression as “the woman’s film,” but it is based on that same principle: that some particular mode of suffering has gotten baked into a paradigmatic necessity. I am forced to think about this, rather than feel it, because I psychologically don’t need it, and thus don’t get it. The filmmakers expect it to seem inevitable and necessary to the viewer, and it just doesn’t. “Why doesn’t she just, y’know, not kill herself?” I want to ask, at exactly the point when I’m supposed to feel a horrible ache welling up inside me. I’ve certainly felt pre-programmed pangs of recognition in all sorts of other movies, movies that have more to do with my own stuff. But the secret ache behind this particular storyline (trope-line) obviously comes from another kind of life, one that hasn’t been mine.

I wished for years that I could get into opera, because in every aspect other than that opera-y quality it seems like something I would really love. But by now I have come to recognize that no matter how much I school myself and open my mind to it, I’ll never get to where real opera fans are, because that opera-y quality reflects important psychological underpinnings for what goes on at the opera, on and off the stage — and I must accept that it, whatever it is, is not deeply true for me in the way that it genuinely is for its target audience. The question is: what sorts of doom feel necessary, what sacrifices have trapped the audience member in his or her own life? Opera’s baggage clearly has something to do with social roles, if not quite with as narrow a focus as “The Woman’s Film.” I think in the era when these tropes formed, homosexuals and artists and, generally, sensitive men and forceful women (= tenors & sopranos) all felt stuck under the cruel thumb of the social code, just like the oppressed housewives in Haskell’s piece, and thus couldn’t help but identify, unconstructively but sincerely, with doom after doom, penance after penance, consumption after suicide, flung from the parapet until the cows come home.

In fact I would imagine that almost everyone in the 19th century felt to some degree trapped between the intimate encouragements of Romantic art and the restrictive Victorian public reality. (I’m working this out for myself but I recognize, sideways, that this is very well-trod ground for cultural theorists. If you want to read (and then shrug at) an academic treatise on what opera is really about, sociologically speaking, I think pretty much every university publisher has a book for you.)

So I can understand historically. But I can’t feel it. For my psychological part, I feel like I am a pretty good person as I am; all my sacrifices to social pressures have always felt all too contingent and dirty, not the least bit necessary or noble. Not to say I haven’t made them. But I don’t generally get a lot out of operatic tragedy because it doesn’t feel to me like real catharsis; real catharsis would let me cry about the false premises. Tragedy implies the existence of those damnable Fates ruining everything. What Fates? Premises all. My enemies are all people and/or premises. Plus death itself, natch.

I do admire, in the dry sense of the word, that Powell and Pressburger were able to genuinely and classily carry these sorts of ideas intact from the high and hoity world of opera (and, yes, yes, more to the point, ballet) over into film. Their movie at least doesn’t feel quite as kitschy-clueless as the same plot does when it appears in Hollywood movies; here it feels like there is some real expressive continuity with the cultural world the movie is about. It feels distinctly well-pedigreed. And outside of the dubious tragedy, I actually found that very gratifying. In fact even the dubious tragedy I can appreciate for its aura of sincerity. One feels this movie has been made in exceptionally good faith.

The opening moments, when eager young music students bound into the balcony seats to see their teacher’s ballet score, seemed wonderful to me: invigoratingly genuine and unapologetic about taking this world and these passions seriously. It gave me opportunity to reflect on the anxieties that attend all my enthusiasms, and so many others’ today. “Elites” have to contend with being “elites” one way or another; even to those who detest it, the Marxist critique hangs in the air and must be swatted away. Here there was no swatting because there was nothing to swat at: the movie really is about the ballet, the ballet, the wonderful ballet! Having to die for art is a bit silly, but being passionate about it is not, and before the movie gets silly it is not silly at all. Valuably so.

The movie has all the polish and ease of Hollywood product but is decidedly well-bred at the same time, a combination that is, to this American viewer, disarmingly rare. British films seem so often to fall too far to one side or the other of the Atlantic stylistic divide. (Though I guess I also admired The Long Good Friday for getting it right.) Moira Shearer is, in a way, the embodiment of the same unexpected combination. She certainly looks and sounds like a “movie star,” and yet she also seems genuinely relaxed and confident and educated and entirely unbrittle.

That sense of ease, and of place and color and texture, is plenty rewarding enough. I would have loved this movie to have exactly the same atmosphere but no plot. No rise and fall, no love triangle, no tragic choices. Just what it’s like to be in the business and put on a ballet. A few passing hints of darkness would have meant far more to me than explicit doom. The centerpiece of the film, the otherworldly “Red Shoes” ballet, is already intended to be read as a compressed dream-parallel of the real characters’ lives. Great! That’s enough then. All the filmmakers’ ideas about the sacrifice and obsession of art would have come across just as clear even if they had only been delivered surrealistically in the ballet. The sequence is as great and striking a thing as they say, lush and weird and cared-for, a cousin to the brief Dali dream in Spellbound and clearly the source for many dream ballets to come. To my taste, that should have been the one window through which the winds of doom blew across the face of this movie. That is the real nature of art, after all: it is the window. I wish the filmmakers had been content to keep the functions of the frame and the centerpiece separate.

Or else let them bleed more thoroughly together and have the whole story be blatantly run through with surrealism and menace. In fact perhaps this is the better critique. The commentary talks about the movie as a Hoffmann-esque fairy tale. If that were how it really played, my tolerance for doom would have been much broader, since in fairy tales, doom seems like an expression of general fear rather than specific angst. It is the relative Hollywood-naturalism of the main story (up until the last few minutes) that makes the tragic outcome seem like something self-pitying and psychological. (The commentary eventually says that the film “goes a middle route,” which is exactly my complaint.)

To summarize: I’m always game for a dream of rich color, and this is a very fine one, but it’s too obviously not my dream. If I dreamed it I would suspect I’d been Incepted. I will gladly watch the ballet sequence again any time I come across it. The rest I can certainly get something out of but not quite as much as I wish.

Debra Messing and Walt Disney are both very appealing and give the movie its natural magnetism. Zeppo is fine I guess.

Robert Helpmann, whose presence really rubbed me the wrong way in Henry V, was just as unpleasant here. I get a very nasty, vain vibe off of him. Reports are that he liked to be mean to everybody, confirming my impression. I know it’s a gay “type” but that doesn’t mean it’s not also a hateful type. His ballet choreography is good enough — Moira Shearer says something similarly unenthusiastic in her interview. Apparently he was a moderately big deal.

The presence of the real Léonide Massine forms a strange bridge between the actual world of the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev, Stravinsky, De Falla, Prokofiev — which in my mind is faraway and long-lost and classy — and the world of Hollywood, the cowardly lion and Cary Grant, which lives on in a perpetual and cozily garish present. How anyone could have wandered from one to the other is beyond me. Like that clip of the guy on “I’ve Got a Secret” who witnessed Lincoln’s assassination (the real Lincoln). Massine just looks like some guy, some guy who’s not above playing movie make-believe.

Criterion has done their standard nice job. Netflix twice sent me the old 1999 disc instead of the listed 2010 edition, but I wasn’t going to miss out on the fancy restoration, so I waited until I could get a library copy. I’m glad I did. The color is lovely and the color is the point. Commentary is a hodgepodge of interview materials with a host, but very well assembled and consistently interesting.

Martin Scorsese is all over the extras, telling us in various ways how much he loves the movie. It makes sense to me that he would. But it’s also a little odd to think about him deeply identifying with a ballerina. His comments all reveal his sensitive eye and cinematic sense; I would gladly listen to him do a commentary track on any movie. Here is his much more concise (and positive) way of saying, in the commentary, more or less what I’ve said above:

“…in a funny way, the love story, for me, is almost just a device. Really just a device to hinge all these—— this recreation of a world, where, as Michael [Powell] put it, “art is worth dying for.” I don’t know if I’d agree with him, but… that’s what the film’s about apparently. I didn’t know that. I—— [begins laughing] He told me that once! [stops laughing] But it’s great to have that kind of passion. I think it’s great to have that kind of passion, if you agree with it or not, that art is worth dying for. For filmmakers to get together and concoct this and perpetrate it onto the world, at that time, is fascinating. The guts and the risk that they took. Especially after World War II. What I like about it sometimes: it seems out of control, that their emotions are out of control. Not the characters but the people who made the film. That the passion is out of control and I think that’s something that’s very rare. Something very rare is created when that occurs.”

Bizarre bonus feature is a full-length audio track of Jeremy Irons (!) reading the novelization (!) written by P & P themselves much later, commissioned by Avon Books in 1977. I’ll admit I didn’t listen to the whole thing; it seems like a decent enough novelization. Jeremy also reads the original Andersen tale, which I had not read before and which unsurprisingly merits a Yikes.

So, music. This is of course one of those movies where the score is really built into the action – i.e. where there’s a composer character who writes music that we hear, plays it on the piano, etc. In the first couple decades of sound film there was a lot of that sort of thing, but I think this is the first in the Criterion Collection to go there (unless you count Spinal Tap and “Lick My Love Pump”). Score is by Brian Easdale, pretty much known only for his Powell & Pressburger scores and for this one in particular. From what I’ve heard of his music, he was a real talent, as good as the much bigger names in film music, and with a touch of the high in his technique that goes a long way.

Though it is so very, very long, our musical selection simply has to be the ballet, which is one of the most significant “classical compositions” in all of film scoring, and perhaps the single best diegetic work of art (“opus Hollandaise”) in any movie. (I could swear this subject had been discussed long ago on this site but I can’t find it right now.) This ballet seems to me comparable in quality to the most renowned “real” American and British ballets of the same era, including the two by Bernstein that have always been favorites of mine… but the use of ondes martenot, quite a few shock chords, and some shameless “dream sequence” special effects (wind machine!) also give it a distinctly cinematic sound, as much a relative of Rosza and Spellbound as of Bernstein et al. A sort of perfect amalgam of a “cinema-ballet” style.

So I guess disc 2 of our Criterion soundtrack anthology will have fewer tracks on it than the first, because this one runs 15 minutes long. Here it is, track 44. This is Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

The recent commercial recording gives a movement breakdown. I don’t have access to that recording so this is somewhat speculative, but based on their timings I imagine those movements begin at these times in our original track (+my summary of the action):

0:00 I. Allegro vivace [The shoemaker / The girl and the boy / She wants the shoes / She gets them]

2:28 II. Allegro moderato e molto ritmico [Dance of the shoes / Nightlife]

3:50 III. Poco più mosso [Dance hall / The scene dissolves]

5:13 IV. Lento tranquillo [The girl heads home / The shoes won’t let her]

6:05 V. Largo [She is trapped / Into dream landscape / Pas de deux with newspaper]

8:09 VI. Presto, quasi cadenza [The shoemaker reappears / Lost in an underworld / Alone]

10:14 VII. Allegro assai [Ballroom / Pas de deux with lover / Waves of applause]

12:41 VIII. Sostenuto [Church / She is forbidden to enter / She tries to cut off the shoes / She is danced to death / The shoes are removed / The shoemaker retrieves the shoes and offers them to the audience]

The piano score was published in 1950 but it’s quite rare. They did play this at the Proms a couple years ago.

You know, watching that yet again just now to type up the action, I feel like I must say: the sequence is really very good. A warm, spooky embrace. At the moment when the hopelessness peaks and the camera begins to pull back (at 9:30 in the mp3) I consistently get a little rush of I-don’t-know-what-emotion-this-is emotion. That’s the supreme form of aesthetic experience, I think. This movie has a lot to offer. Maybe I’ll grow to accept the rest of its embrace, on its own terms, on subsequent encounters. But for now I’ve watched it enough.

Sentences are not forming very well for me right now and this whole overlong entry comes from the tedious rather than the breezy part of my brain. I’m not at all pleased with what I’ve written here. But I’m just going to move on to the next movie rather than wait around for a breeze. All in good time.