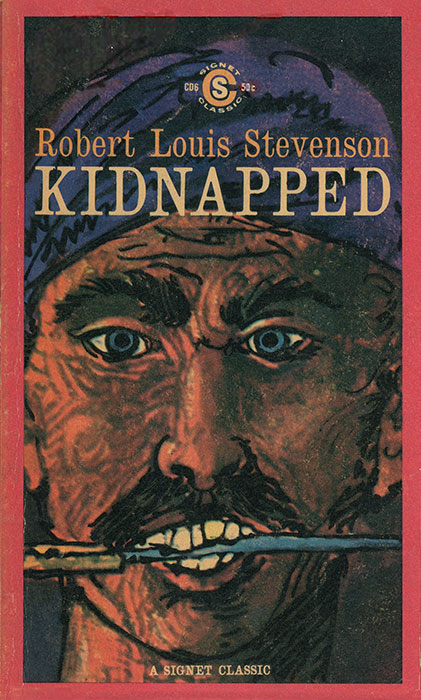

CD6, 50¢, August 1959. Cover artist unknown. 239 pp.

This glorious passport to romance and high adventure has delighted generations of readers. It is the story of young David Balfour, an orphan, whose miserly uncle cheats him out of his inheritance and schemes to have him kidnapped, shanghaied, and sold into slavery. But justice triumphs — after a spirited odyssey which includes a shipwreck, a hazardous journey across Scotland with a daredevil companion, intrigues, narrow escapes and desperate fighting. Rich in action and characterization, this exhilarating novel was considered by Stevenson to be his finest work of fiction. Henry James called Kidnapped, “Stevenson’s best book.”

With an Afterword by Gerard Previn Meyer

Audiobooks of Kidnapped average around eight hours. It took me approximately ten months to read it. Not busy months, either.

Part of it is simply that my attention is currently very poor. A substantial portion of my brain is constantly flitting around like a moth. After picking up a book I often end up setting it back down after only a few sentences because the moth is spoiling the experience.

Another part of it is that I started Kidnapped three times: the first time getting about halfway, and the second time nearly finishing — maybe three feet! But each time my rhythm was interrupted by some event. This is the kind of book that wants to be read in one continuous burst of fantasy, so picking up in the middle after an extended absence seemed inappropriate. Whereas of course the prospect of having to begin again — and then yet again — was intrinsically untempting, and a certain amount of willpower needed to be accumulated first. Thus delay begat delay and here we are.

So it took me all year, but don’t let that dissuade you from reading it. It really will only take eight hours, and they’ll be eight hours spent in very fine company.

The first half of Treasure Island is my gold standard for prose storytelling. It’s like Mozart: so pure and perfect that children can take it for granted. Everything is simply the way it has to be — “and why wouldn’t it be?” Its naturalness is so complete that one forgets it’s an achievement. All seems equally innocuous, unlabored, unfussy, unremarkable — all the power flows back to the root, to storytelling itself, to the enchantment. It is ordinary and magical.

Kidnapped showed me that it wasn’t luck; it’s all craft. Stevenson writes like a master film editor. He has excellent intuition for the choreography of attention, its rhythms and patterns and tendencies. We never notice the ship being steered; we simply see next what we ought to see next. I made a point of visualizing a movie version as I went, directing each shot in my head, taking the text to be a continuous voiceover. The pacing of the prose allowed for this, where most wouldn’t — witness for example Signet’s next at bat, Thomas Hardy, who switches from 78 RPM to 33 RPM willy-nilly — and this speaks to exactly what I’m admiring: all Stevenson’s moves are the real moves of a living, active, youthful mind. Dipping from surface to depth and back again in graceful, unselfconscious motions, casting an eye around a room and then to the face of the person speaking and then inward and then out, etc. etc. He experiences the story in time and space, he breathes its air and sees what it sees.

Treasure Island is wonderful, but an adult reader with an overcomplicated adult brain may find the tempo too brisk to fully register. It’s been written for children, who experience weight and time in everything, no matter how fleeting. Kidnapped feels distinctly more grown-up; the style thinks a bit more, observes a bit more. Jim Hawkins is about 13 or 14 (isn’t he?) whereas David Balfour is 17, and the book is accordingly that much further toward maturity. But Stevenson has an idea of “maturity” that does not in any way repudiate or supersede youth and innocence. This is to be admired.

In the afterword by Gerard Previn Meyer, there’s a quote from Stevenson that I found inspiring:

The true realism, always and everywhere, is that of the poets: to find out where joy resides, and give it a voice far beyond singing. For to miss the joy is to miss all. In the joy of the actors lies the sense of any action. That is the explanation, that the excuse.

He expands on this in the full essay from which it comes (which I think is worth reading in its entirety): any notion of “realism” that opposes it to so-called distortions of Romantic emotionality is not just an aesthetic failure but a philosophical one. Emotion-infused experience is real and emotionless experience is not real. We should not call the elimination of emotion “clarity” when really it’s just a form of fear. This philosophy comes through in the writing. David Balfour’s naivete, and his experience of the world as sensation first and foremost, is depicted as putting him constantly at risk — but this risk is embraced, and celebrated. The risk is the joy, in the telling of a story like this! (Look at the title!)

This is an outlook I endorse and aspire to. An innocent stumbles out into the world and is horribly misused and endangered and beset by pain and suffering… and it’s all terrifically worthwhile because the world is splendid. Innocents are foolish but innocents are also right. That’s as worthy and evergreen a philosophy as can be put in a book, isn’t it? I think full and capable commitment to this principle qualifies Stevenson as a great artist. Again: there’s something of Mozart to it.

Kidnapped only strengthened my impression that Huckleberry Finn is deeply flawed. What was Twain trying to achieve with his characters if not this? What do Twain’s admirers want to claim for him if not this? But put these authors side by side and tell me which is the more true. Stevenson takes the open-eyed, sensation-hungry worldview of a boy and lets its gaze occasionally pass over glimpses of depth, until a full adult world can be sensed looming; whereas Twain takes the jaundiced worldview of a cynical adult and tries to leaven it with dollops of childlike sensation, retrieved from a jar.

Alan Breck, David’s companion through most of the book, very much stands out as a an author’s subject, a project, a portrait bust. Stevenson set himself the task of painting a man on the page, the way a “high” author like Henry James would — but James would use 10,000 brush strokes and make the reader wait. Stevenson’s technique for character is of a piece with his technique for story: convey whatever a boy would take in, and when he would take it in; no more and no less. The individual strokes may seem broad, theatrical, but the balance of their combined placement is a really fine achievement. Alan’s vanity and resourcefulness and pettiness and generosity, Alan as big brother and Alan as foreigner, etc. etc. Long John Silver is a similar achievement, because he’s a similarly mixed bag, but he’s ultimately a character for Jim to overcome, whereas Alan is a character for David to embrace (with reservations), so his dimensionality is that much more significant to the reader. Television writers ought to study him. They ought to study Stevenson in general. This was “real art in a commercial mode” exactly in the way that the best TV is.

I found the ending very strongly affecting in the emotional truth of its abruptness. No winding down for form’s sake! Stevenson’s sincere feeling for the characters has guided him this far, and as soon as the feeling has crested, the story stops itself because it knows as well as you that what’s done is done. We reach a long-foreseen wistful inevitability… “and so it came to pass, and to yammer on about lesser things now would be in poor taste, so let’s stop.” The final sentences are superb, a hand-closing-the-storybook-at-the-end-of-the-Disney-movie gesture done as well as I can imagine it being done.

I’m sure this all sounds highly enthusiastic, so I must now admit: I probably wouldn’t have had the patience for this book as a child, because of all the time and attention given to Scottish ways and Scottish sights and Scottish lore and Scottish history and Scottish politics and all manner of Scottish color, for which I would have had no framework of interest. And even now it seems to me somewhat to the side of the book’s real strengths.

Plus I continue to find written-out dialect to be an aesthetic error, almost a vice. It’s a trap for writers: when you’re trying to turn human observation into words, it might seem like the purest expression of your art would be accurate transcription of the quirks of how people talk. But, alas, that’s nae the way! Wheesht, man! I cannae tell ye it any clearer! The difference between the narrator’s idiom and the idiom of the characters becomes a conspicuous gap, implicitly skeptical; it can’t help but make the author seem more aloof and the dialogue less immediate, and who needs that?

At least Stevenson’s indulgence is far milder than Twain. And to be fair, given the setting, some dialect was obviously inevitable. My distaste is just for stuff that feels like it goes beyond the inevitable, that excitedly pursues dialect as an end in itself. It’s something for which the printed word is intrinsically ill-suited and so should be handled with appropriate delicacy.

David becomes very ill at least three times, and dangerously exhausted several times as well; there is a definite emphasis on depicting the experience of mentally and physically compromised states. That’s the sort of thing of which Pincher Martin was composed almost exclusively — and I note a striking resemblance, perhaps more than coincidental, between that book and the episode here in which David is stranded on a tiny island (so he believes), sleeping on a stone, battered by the rain, and eating nauseating shellfish to survive.

For our excerpt I’ve decided to go with one of these sorts of passages; it’s the sturdy, eager fascination with hardship that I think is so distinctively healthy about this book. Here’s David immediately after having been konked on the head and, spoiler alert, kidnapped:

I came to myself in darkness, in great pain, bound hand and foot, and deafened by many unfamiliar noises. There sounded in my ears a roaring of water as of a huge mill-dam; the thrashing of heavy sprays, the thundering of the sails, and the shrill cries of seamen. The whole world now heaved giddily up, and now rushed giddily downward; and so sick and hurt was I in body, and my mind so much confounded, that it took me a long while, chasing my thoughts up and down, and ever stunned again by a fresh stab of pain, to realize that I must be lying somewhere bound in the belly of that unlucky ship, and that the wind must have strengthened to a gale. With the clear perception of my plight, there fell upon me a blackness of despair, a horror of remorse at my own folly, and a passion of anger at my uncle, that once more bereft me of my senses.

When I returned again to life, the same uproar, the same confused and violent movements, shook and deafened me; and presently, to my other pains and distresses, there was added the sickness of an unused landsman on the sea. In that time of my adventurous youth, I suffered many hardships; but none that was so crushing to my mind and body, or lit by so few hopes, as these first hours on board the brig.

It’s about suffering and nausea and utter despair, but notice that it’s also about the neverending thrill of sensation. “The thundering of the sails!” In my imagined movie version such stuff was depicted as simply and accurately as possible; no Romantic exaggeration is necessary to find the power in it. Sails really do make that thundering sound, and you really could hear it even if you were lying in a state of pain and terror in the hold.

I take this as a kind of primer on how to experience suffering: with such clarity and vigor that a boy would enjoy reading about it.

All the covers.

CP553, 60¢, ~1971.

First price bump, design unchanged from the original seen above. Once again it seems like the layout had to be reconstructed after the first print run: in the first edition the fellow has more or less white teeth; in all subsequent appearances he has one obviously gold tooth (see below).

Hey, speaking of the fellow with the gold tooth: this is pretty clearly a cover illustration by someone who didn’t read the book. “It’s about pirates, right?” Unscrupulous sailors do appear in Kidnapped, but they’re only in a couple chapters and hardly represent the book as a whole. And they’re just described as run-of-the-mill workaday badmen; they don’t have bandannas or knives in their mouths or gold teeth. They’re not pirates. This cover is, frankly, wrong. Didn’t stop them from using it for 25 years.

Typeface is Century.

CT744, 75¢, 1974.

CQ881, 95¢, 1976.

CY1035, $1.25, 1978.

CW1194, $1.50, 1979.

??1602, $?.??, ????.

70s branding. Looks like Miss Cross’s copy is one of these.

CW1754, $1.50, 1982?

The “centered logo” phase.

CJ1972, $1.95, 1985?

CE2333, $?.??, 1987?

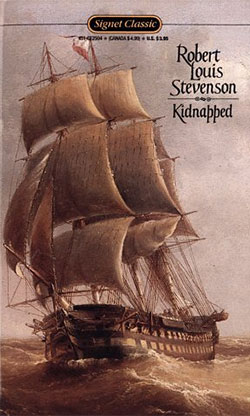

CE2504, $3.95, 1991?

The 80s cover: detail from a painting apparently called North Sea Passage, by one Henry Redmore, an unstoppable producer of this sort of thing. A dull choice but it cannot be denied that there is a ship in this book! To be fair: if you’re restricted to stock artwork, Kidnapped is a pretty tough assignment — there are plenty of enticing paintings of the Scottish highlands, but they’re generally serene and uninhabited, and of course the cover needs to suggest action. A ship on a choppy sea sort of solves the problem. It’s just awfully generic.

Typeface isn’t Ludovico or Zapf Chancery or Catull or El Greco; I can’t figure out what it is. The lowercase “p” is extremely distinctive. Let me know. (I suppose it’s possible that this isn’t from a published font, and is just assembled from a calligraphic alphabet found in some book. But more likely it’s a typeface that never made it to digital and is now effectively defunct. Damn you Macintosh!)

2768, $3.95, 2000.

With a new introduction by John Seelye

Here they bite the bullet and accept that no stock artwork can better the famous Wyeth illustrations, which entered the public domain in 1988. Certainly this is a wonderful illustration… but maybe not the best choice for a cover. “What’s going on here?” one might well ask. “What kind of character is that guy in the coat and how am I supposed to feel about him?”

Plus Signet has made sure to present it in the least flattering possible context: a yellow parchment texture that makes the painting look washed-out, and a distracting “angled rip” framing that spoils the composition. Presumably the intention is to suggest that an EXCITING PIRATE has whipped out his sword, avast ye!, and SLICED THRILLINGLY through the parchment to reveal this illustration beneath. All that and a little shell design because why not. No, that’s not a logo, it’s just a little shell design. To fill space. That’s all.

The Seelye intro is passably relevant but awfully academic in tone.

Typeface is Baskerville.

3143, $4.95, 2009.

With a New Afterword by Claire Harman

“Oh what’s that you say? You say we should give it a rest with the pirate stuff? Well just for that we’re gonna put goddamned BLACKBEARD on this cover! Yeah, you heard us! Kidnapped is about BLACKBEARD THE PIRATE now, and there’s nothing you can do about it!”

It’s a near-certainty that they found this painting by typing “pirate” into an image service search engine. Oh well. At least it’s colorful.

Typeface is Windlass. You know, for pirates.

“We should not call the elimination of emotion ‘clarity’ when really it’s just a form of fear.” You probably no longer embroil yourself in the Scott Adams Twitter Experience, but this made me think of him and his minions.

I should confess that the use of the word “fear” is all me; Stevenson’s essay doesn’t go there. He just says that hidden inside even the driest husk of a person there still survives a secret inner fire. He doesn’t get into detail about what the husk is up to.

But yes, there’s a whole world of people out there — on Twitter and elsewhere too — using the words “rational” and “logic” as shields.