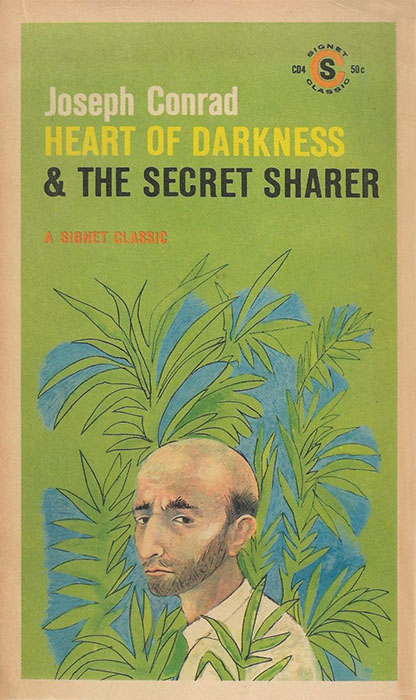

CD4, 50¢, August 1959. Cover artist unknown. 160 pp.

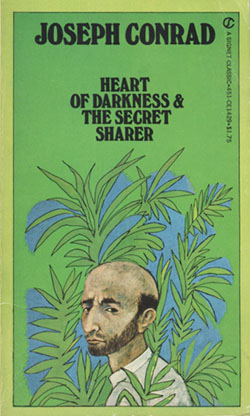

(This cover, like Tom Sawyer’s, seems to have been painstakingly traced and redone at some point in its first couple of years. Compare. In this case the above is the first version; subsequent editions (see below) use the recreated illustration.)

The dark places of the human soul — this is the region that Joseph Conrad so brilliantly explores. In the steaming jungles of the Congo or the vast reaches of the sea, it is man’s capacity for good and for evil that is his enduring theme.

Heart of Darkness tells of a powerful European, Kurtz, who reverts to awful savagery in an isolated native trading post.

The Secret Sharer describes the terrible conflict of a young captain who is torn between his duty to his ship and his loyalty to a young officer with whom he identifies himself after the murder of a mutinous crew member.

Compelling, vivid, exotic, suspenseful, these are among the half-dozen greatest short novels in the English language. “To make you hear, to make you feel, above all to make you see” — this was first and last, the aim of Conrad.

With an Introduction by Albert J. Guerard

I was assigned both of these in or around 10th grade, and read them in my trademark style, bounding over the text like a stone over water. A lot of description? Skip it. Somehow I was never properly taught how to read descriptive passages. My instincts told me that attempting to achieve visual effects in prose was futile, and I wished authors would know better than to try.

Here’s your first excerpt, the opening paragraph of The Secret Sharer:

On my right hand there were lines of fishing stakes resembling a mysterious system of half-submerged bamboo fences, incomprehensible in its division of the domain of tropical fishes, and crazy of aspect as if abandoned forever by some nomad tribe of fishermen now gone to the other end of the ocean; for there was no sign of human habitation as far as the eye could reach. To the left a group of barren islets, suggesting ruins of stone walls, towers, and blockhouses, had its foundations set in a blue sea that itself looked solid, so still and stable did it lie below my feet; even the track of light from the westering sun shone smoothly, without that animated glitter which tells of an imperceptible ripple. And when I turned my head to take a parting glance at the tug which had just left us anchored outside the bar, I saw the straight line of the flat shore joined to the stable sea, edge to edge, with a perfect and unmarked closeness, in one leveled floor half brown, half blue under the enormous dome of the sky. Corresponding in their insignificance to the islets of the sea, two small clumps of trees, one on each side of the only fault in the impeccable joint, marked the mouth of the river Meinam we had just left on the first preparatory stage of our homeward journey; and, far back on the inland level, a larger and loftier mass, the grove surrounding the great Paknam pagoda, was the only thing on which the eye could rest from the vain task of exploring the monotonous sweep of the horizon. Here and there gleams as of a few scattered pieces of silver marked the windings of the great river; and on the nearest of them, just within the bar, the tug steaming right into the land became lost to my sight, hull and funnel and masts, as though the impassive earth had swallowed her up without an effort, without a tremor. My eye followed the light cloud of her smoke, now here, now there, above the plain, according to the devious curves of the stream, but always fainter and farther away, till I lost it at last behind the miter-shaped hill of the great pagoda. And then I was left alone with my ship, anchored at the head of the Gulf of Siam.

No way would I have read any of these words, as a 10th-grader. I would just let my eyes drift down it, waiting to be stopped by the subliminal sparkle of an active verb — like looking for Waldo. He’s not here! Onward. And I still feel that temptation sometimes, to rush past the painting and get to the acting. But it turns out that when I force myself to stop, move very slowly word by word, and paint, I enjoy the task.

I think what I was never given the opportunity to learn is just how slow that work can be, compared to other reading. It’s counter-intuitive, after all, since in reality, imagery is taken in very quickly whereas action is intrinsically time-consuming. In prose nearly the opposite. Elementary school students ought to be given the assignment of reading passages like this and then actually drawing everything that’s described. (For all I know, maybe I was given that task, and then later decided on my own that it would be preferable to outrun it. Oops.)

Conrad limits large-scale paintings like the above to a few choice spots, but he’s not shy about taking the brush in hand. In addition to the visual effect I think it also creates an important psychological impression: the overabundance of words demanded by each picture suggest a narrative anxiety. Conrad and his narrators are overthinkers, in environments that give them plenty of space to run. When I was a kid, excess of detail felt like a miscalculation, but now that I’m an anxious adult I recognize the mental mode from which it springs: overdescription is what it feels like when too much conscious thought crowds each moment. All that noticing is a burden, even as it notices well and with pleasure, and in a sense, the weight and quality of that burden is what Conrad’s work is really about. What’s it like to be a man of the world, a man at sea, but be thinking and feeling all the damn time? It’s hard.

I went in a bit wary that Conrad might be a zone of masculinity in some off-putting, puffed sense — and indeed there is a marked “manliness” of both style and substance, but it never grates because he comes by it honestly, and also clearly has profound reservations about the whole package. Running silently through both of these stories was the subliminal implication that being a man is more or less the same thing as being traumatized. That, I think, is how biography, subject matter, and style ultimately link up. Heart of Darkness ends on this note: women wrongly believe that life is good and meaningful, but the prospect of actually destroying that illusion is too much, too depressing, for a man to go through with. Of course the woman and the man are both in his head.

Heart of Darkness seems to be a rendering of the most traumatizing experience of Conrad’s life, and it is indeed a masterpiece. I’m with the consensus on this one. For the first half of my reading I felt prepared to call it an “absolute masterpiece”; in the second half I had the sensation of there being some lumps in the pudding, and some burned bits. But that’s really a quibble. The scope of what Conrad takes on, here, and the ability to construct the thing so that it does in fact take it on, is to marvel at: nothing less than the equation of politics with philosophy with psychology, made concrete and harrowing, fully modern in 1899. Its grip is very firm.

“The horror! The horror!” is generally interpreted as being Kurtz’s report on a cosmic vision, his judgment on the soul of man and the nature of existence and all that; it’s all “a horror.” Sure. But I propose that he might equally and equivalently be describing an actual emotion, particular to him. An underlying horror is the impulse that has driven him in all his amorality, now finally laid bare to his self-awareness. And the deep resonance of the story, for its mesmerized witness Marlow/Conrad, is his own persistent inner sense of horror. That is, I’m again saying: there’s a whiff of PTSD here. “I felt I was becoming scientifically interesting.” A wonderful phrase for a sad thing, from someone who knows.

The Secret Sharer pales in this company — it’s much smaller-scale, and simpler in technique and intent — but it’s still a forceful little story with a striking premise. It comes first and makes for a suitable opening act.

The two works are linked by psychological elements that I can’t help but note are also recurring themes in my Twilight Zone entries: the doppelgänger-projection of a detached inner self; the implicit menace of the world, of society, of one’s fellow man in all his unknowability. Rod Serling, as a soldier, had also been a bit traumatized. For what it’s worth.

Guerard’s introduction pushes a psychological interpretation, pretty similar to mine; it seems like the idea of pairing these two items into one volume might have been his. I felt his sale was maybe a little strong-armed for an introduction — hey, let us make up our own minds! — but it’s well-written enough.

Okay, since there were two works here, we’ll do a second excerpt too, from Heart of Darkness. Marlow has just arrived at a Belgian station in Congo and has found a chaotic scene of pointless activity, broken equipment, and brutality.

You know I am not particularly tender; I’ve had to strike and to fend off. I’ve had to resist and to attack sometimes — that’s only one way of resisting — without counting the exact cost, according to the demands of such sort of life as I had blundered into. I’ve seen the devil of violence, and the devil of greed, and the devil of hot desire; but, by all the stars! these were strong, lusty, red-eyed devils, that swayed and drove men — men, I tell you. But as I stood on this hillside, I foresaw that in the blinding sunshine of that land I would become acquainted with a flabby, pretending, weak-eyed devil of a rapacious and pitiless folly. How insidious he could be, too, I was only to find out several months later and a thousand miles farther.

That nearly gave me chills, when I read it. These days I spend more than enough time contemplating the flabby, pretending, weak-eyed devil of rapacious and pitiless folly; I felt and knew exactly what he was talking about before he put the excellent words to it.

CP523, 60¢, 1972.

CT824, 75¢, 1975.

CQ1004, 95¢, 1977.

CY1221, $1.25, 1979.

CE1429, $1.75, 1980?

New branding and 70s typography to match.

CW1668, $1.50, 1982? (price drop!?)

Centered logo.

CW1668, $1.50, 1983?

CE1893, $1.75, 1983

CE2072, price unknown, 1986?

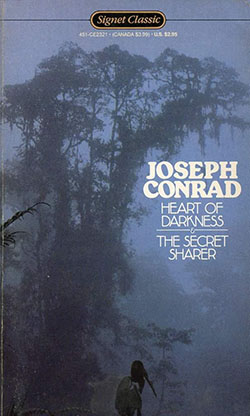

CE2321, $3.95, 1989?

Once again, a tasty 80s revamp. The terrifically atmospheric image (which wraps around, by the way) is credited in the book as “cover painting by Fritz Trupp,” but Fritz Trupp turns out to be not a painter but an anthropologist. I think there must have been some sort of miscommunication from the art department; surely what we’re looking at here is a photograph rather than a painting, presumably one extracted from Trupp’s book The Last Indians: South America’s Cultural Heritage, published in 1983, that same year.

In other words: it’s the wrong jungle. But that’s okay. It’s cinematic and it looks the part.

2657, $4.95, 1997

That was a great cover, but guys, we’ve got a problem: it’s too mysterious and engaging. How can we put a damper on that? I know, dump the palette, and blot out most of the visual interest with a big rectangle. There we go, now it looks dull as can be; in fact you can hardly even tell what you’re looking at anymore. Perfect.

Another late-90s downgrade. Joyce Carol Oates shows up to try to compensate, but to no avail: her comments are shallow and unenthusiastic; she doesn’t seem to like Conrad all that much. The only part where she perks up — distastefully so, to my mind — is when she goes through the motions of giving him a pointless drubbing for his supposed crimes against PC. She seems to really relish that. “I’m bringing all my scholarly skills to bear, here, so listen up: when you really break it down, this story is awfully Eurocentric in its worldview, tsk tsk tsk.” NO SHIT, CAROL! THAT’S THE STORY! I’m rolling my eyes just typing this.

3103, $4.95, 2008 (Now OOP)

This is simultaneously bland and garish, and is clearly just a tacky Photoshop manipulation of a bit of stock imagery, but let’s admit it: it could be worse. At least it’s trying to entice us. New piece by Vince Passaro is unpretentious and on point; as with Tom Sawyer, the most recent commission was the most rewarding to read. A pleasant surprise, that!

I read in high school the way you say you read in high school. I wish I could commit to reading many of these works again to see what is really there, what was there all along. To take the time. I know I can’t. There’s too much, and too many things remain that I haven’t read even once. I get vicarious satisfaction in knowing that you are reading these things, and in being able to read your posts after you do. And in a non-vicarious manner, I’m just glad for you.

In fairness to youth (and descriptive imagery), that’s a hell of a tough passage to take in. Just consider the word

choices: “mysterious,” “incomprehensible,” “nomad,” “barren,” “foundations,” “solid,” “still,” “stable,” “smoothly,” “imperceptible,” “anchored,” “straight,” “flat,” “stable,” “unmarked,” “leveled,” “insignificance,” “small,” “impeccable,” “mass,” “vain,” “monotonous,” “impassive,” “fainter,” “farther,” “alone.” The heaviness and stillness is oppressive, even to my adult eye, presumably intentionally so.

Compare that to a descriptive passage from, say, The Great Gatsby, which is full of description and also was my favorite book in high school:

As a teenager I wanted to like Conrad — I had the impression that he was sophisticated and troubled — but the actual experience of reading him was chalky, drab and dankly male. Maybe I would feel differently now but it seems undeniable this is intended to be a, uh, thick pleasure.

I hear you. It is indeed “thick” and “troubled.” But this time, when I paced myself, I found to my surprise that it was not drab; there’s a sense of urgency in it. For better and for worse it’s not a diversion, it’s the thing itself; one has to take it or leave it. Which is pretty much just a matter of one’s mood.

Comparing to that Gatsby passage is pretty jarring. Like pointing out that a New Yorker cartoon is a bit breezier than a Turner. Well, yeah! I think there’s room in the world for both brush sizes.

But for what it’s worth: I probably wouldn’t have read those Fitzgerald paragraphs either, in high school. Would have winnowed it to the first and last sentences, and not having read the rest, would have been confused by “the two young women ballooned slowly to the floor,” but still moved on, confident that it didn’t matter.

If anything the Fitzgerald is harder to read, because it requires not only the patience for the purely visual, but also sensitivity to fine gradations of irony and sincerity. How much genuine pleasure is Nick taking in entertaining these similes and exaggerations, vs. how much is he using them to snark at the unexaggerated things in front of him? How much Fitzgerald, for that matter? One can’t determine what it means visually that the grass “seemed to grow a little way into the house” until one has a directorial theory on that point. Whereas in the Conrad the reader’s task is pretty cut and dried: read what it says and picture that.

Very interesting! And how disappointing to read about Ms. JC Oates’ lame commentary. I read Heart of Darkness in college and was really moved by it. I reread it just a couple years ago, prior to travelling to central Africa and was again impressed, and followed it up with the equally impressive history book King Leopold’s Ghost, which, inter alia, discusses the novel and possible real-life inspirations for the characters. I never minded the over-descriptiveness of it — a novel set in a “strange land” sort of yearns for detailed descriptions to really bring you into the milieu. And the book is not very long, which I guess helped with my willingness to slow down the reading pace and sink into a paragraph.

I don’t think I’d even heard of The Secret Sharer — obviously it wasn’t packaged together in whatever edition I found in college.

I’m the worst at compiling a list of books I think of as greats or favorites to proffer to interested questioners who find out I was a literature major. But Heart of Darkness would be on it. I’m not sure I’d yet trained myself to read descriptions in books but it drew me in regardless. It is so intensely the thing it is trying to be. I didn’t find it manly, just a driving, unstoppable horror, but maybe that’s because I’ve never had to grapple with the expectations of masculinity so didn’t recognize it when I read it.