2001:

directed by Arthur Crabtree

screenplay by Herbert J. Leder

original story (1930) by Amelia Reynolds Long

Criterion #92.

I guess there wasn’t enough money in the budget to pay for a face.

One of course is tempted to ask Criterion “why?” but I tend to think those are worms best left canned. As for asking myself “why?” the answer is of course “because it’s Criterion #92!” The buck stops there.

I had hoped to return to my Blob theme of “what makes amateur filmmakers tick,” but Fiend can’t really sustain it; its amateurishness isn’t nearly as striking or distinctive. In fact it’s just good and smart and commercial enough that I was able to feel embarrassed for it. Despite being British-made it’s hardly distinguishable from a standard American B: gawky and simple-minded and all too by-the-book.

Like many creature features, it consists of a bunch of dullards treading water until the last 15 minutes, when it’s finally time to reveal the goods. Usually the goods are a guy in a rubber suit or a puppet on strings, but in this case a modicum of care has been taken and we get something almost memorable: an animated horde of crawling brains, inchworming around by their spinal columns. An actor fires a gun offscreen and then we cut to goofy pixilation of a punctured brain belching out what seems to be grape jelly. This happens about 20 times. I guess for 1958 it was astonishingly bizarre and disgusting. Now it’s just odd and mildly grody. Oh well: I’ll take it.

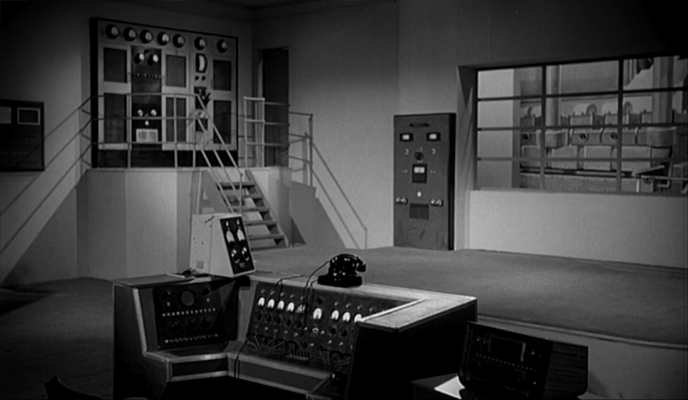

The original 1930 short story, The Thought-Monster, is about as undistinguished and derivative a weird tale as you can imagine. But it’s flattered by the transfer to a cinematic genre where nobody expects any plot beyond “it’s from space and we need to kill it!”; in this context even limp secondhand ideas start to seem sort of interesting. Turns out these creatures aren’t from space: they’re the byproduct of psychic experimentation. They are, in fact, somehow the physical concretion of thought itself. Super-powering the brain gives it telekinetic control over external things, and then ultra-super-powering it gives it the next power beyond that, which turns out to be the power of self-projection — effectively the power of creation. A strange and dreamy and potentially disturbing idea that, rest assured, this movie does nothing with. The entire science-fiction content of the film, such as it is, is condensed into a single narrated flashback that lasts about two minutes. There’s almost a story here, but no storytelling.

Another peculiar sci-fi premise in the screenplay, which doesn’t come from the original story: the idea that a nuclear power plant can somehow beam its energy wirelessly throughout the atmosphere, to be picked up and used by distant planes. (This free-floating wireless energy turns out to be what’s sustaining the monsters.) Nikola Tesla isn’t mentioned, and the technological absurdity is treated throughout as though it goes without saying. Did the screenwriter think this was a real thing? Maybe it represents confusion about what nuclear “radiation” means.

Paraphrasing only lightly: “I wonder who’s committing all these murders.” / “I don’t know, I guess tonight at midnight I’ll go look around the cemetery and if I find a crypt there, I’ll go down into it.” Because naturally there’s got to be a scene in a crypt. So at one point the guy simply picks up a flashlight and we cut to the next scene and we’re in the graveyard. It could just as easily have cut to a haunted mansion or a mysterious bookshop or an abandoned factory and it would have made nearly as much sense. Genre sense.

I hope it’s clear that I’m not complaining. Anyone wants to go down in a crypt in a movie, it’s always fine with me. It’s never the wrong time.

The commentary track isn’t really a “commentary,” it’s just a feature-length interview with executive producer Richard Gordon questioned by Tom Weaver, a nerdy horror-magazine type. Each in his way seems to enjoy the occasion. It feels like it must surely be the definitive 75-minute conversation about Fiend Without a Face.

As with the The Blob, we learn that the producer started his career in distribution. I like this as a framework for thinking about drecky B-movies: they’re essentially movies made by salesmen. The sales rep has his own peculiar perspective on the product; this is what movies look like to people who deal them by the yard.

In one of the other bonus features, Gordon talks about setting up a motorized, noise-making brain in a glass case on a stand in front of the theater showing the movie in Times Square. The film itself comes from exactly the same place. B-movies are PR thinking treated as production thinking.

The action takes place in Canada near an American military base. In his interview the producer says that despite its being shot entirely in England, they decided to set it “on the American-Canadian border” so that it would have appeal in the American market. Little did he realize that the mere mention of Canada would immediately signal to viewers that this was not an American film. I mean, really.

Later in the interview he acknowledges that it’s set on the Canadian border as a hedge against any hints of Englishness that might have crept in. A funny thing to worry about, under the circumstances, but he’s probably right that very subtle cultural absurdities tend to disrupt the audience experience in ways that overt absurdities of dialogue, plot, performance, etc. do not. We all get that this is just a dream; what would really bother us is finding out that it’s not our dream.

In the commentary the apparent grape jelly is identified as: raspberry jam. Well, I was close.

Fiend Without a Face had the great good fortune to be picked up by MGM in what was apparently their very first venture into the business of distributing indie schlock. It was packaged as the second half of a double-bill with The Haunted Strangler (a.k.a. Grip of the Strangler) from the same producers, which had been made simultaneously on a joint budget. So it got rather a more luxurious launch than you might expect for such a thing.

The bonus features on the disc include a lot of period images like the ones I just linked to, as well as the trailers for these and three other Gordon films. Apparently Criterion thought, “no way we’re ever going to distribute the rest of these turkeys, so we might as well stick this stuff here.” Little did they know! Stay tuned for spines #364–#368. (Stay tuned, but don’t hold your breath.)

The last bonus feature is an onscreen essay by Bruce Eder, superior to but still redundant with the one in the packaging, which is by Bruce Kawin. Seems like maybe someone at Criterion screwed up and double-assigned this baby. Kawin never dares to state the obvious, preferring to leave it vaguely hypothetical: “If this movie is formulaic, it also goes beyond formula to a gravely determined and inventive stance of its own.” Eder, after many paragraphs of serious-minded historical hype, finally lets himself speak truth: “In some respects, the movie may seem a bit naïve.” Pretty weak, but at least he got there.

The trailer above notes that the girl “could be a spy.” The possibility isn’t actually raised in the movie, but it’s true that she could be! Anyone could be! If you’re ever bored by a movie that you’re watching, just add a little spice by considering: they could all be spies!

Gordon on the actress Kim Parker:

She was a very nice girl, but she tended to, um… be somewhat difficult in her conversation. And I remember an incident when — because we were shooting the Boris Karloff film Grip of the Strangler at the same time as Fiend Without a Face, and there were occasions when she and Boris Karloff went together by car to the location or studio, and one day Boris Karloff took me aside and said that he really didn’t mind sharing his car and driver with Kim Parker, and she was a very charming lady, but some of the stories she was telling and some of the language she was using he really found rather difficult to accept, and would I either have a word with her about it or perhaps I could arrange for him to pick up somebody else other than her.

And now for all you roiling tumult fans out there, we’ve got a special treat: it’s “Main Title from Fiend Without a Face” by Buxton Orr! Mercifully drowned out by jet engines, in the end.

Actually before we get to the clip I should warn that roiling tumult fans are going to be disappointed by the rest of the score, which mostly leaves the mayhem and monsters unscored — their presence is signaled by Telltale Heart sound effects. Orr is a proficient enough composer of stuff that sounds basically like movie music, but he doesn’t have much of an instinct for matching tone, or for spotting it in at useful moments. The score seems a little distracted, frankly. And who can blame it.

Anyway, get a load of this:

Yippee! I so enjoyed this entry. Delightful to read, beginning to end.

And there is so much to enjoy in the promotional material (in answer to your question: yes, Criterion trailer embedded successfully):

“Does it come from another country or another world?” Really? It might just be from another country? Like what? Lichtenstein? Andorra?

And the photo of the theater advertising “BRUTAL MURDER of YOUNG GIRLS” along with the enticing “Cooled by Refrigeration” is priceless. Oh 1958, you were a hoot.

I’m surprised they depicted the fiend in all the promotional stuff. Wouldn’t you think they’d want to save that for the big reveal in the last 15 minutes of the film?

Do you think Kim Parker was horrifying the King of Monsters on their rides to the set with lurid tales of her rival, the bosomy showgirl Sabrina?