6] Vītols: Piano Sonata, op. 1 (1885)

и. витоль : соната : для фортепиано : соч. 1е.

Sonate : pour le : Piano : composée par : Joseph Wihtol. : Op. 1.

[Sonata : for the : Piano : composed by : Jāzeps Vītols. : Op. 1.]

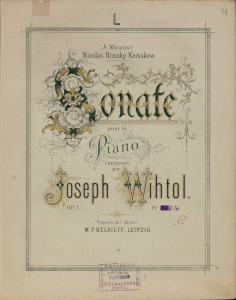

A Monsieur Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow.

• 16 Sonate pour le piano, op. 1 (1886)

16 was made available by Sibley in 2006, which is where the link above goes. But that scan is B&W only. The color/grayscale images below come from a copy digitized by the National Library of Latvia around 2007, which I downloaded back in 2009, along with a few other Vītols scores. Unfortunately, a few years ago the Library had second thoughts about copyright and now only allows these files to be accessed from their premises. But I’ve still got my copy:

Going on the catalog text, this copy seems to be from somewhere between 1898 and 1902; it’s conceivable that earlier impressions of the title page might have had more or different colors.

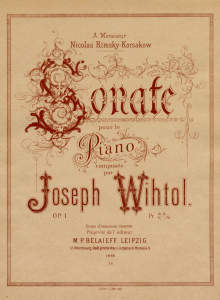

Actually there’s yet a third copy out there, as uploaded to the Pianophilia forums by star user “Alfor,” which is later than the copy seen above, as evidenced by the new price on the title page, with the later exchange rate (I’m pretty sure the original 1886 price, blotted out in the image above, is M 3 / R 1.50). I include its title page here to illustrate my point about how once-fancy designs were reissued in later years without all the bells and whistles:

Jāzeps Vītols (1863–1948) was a Latvian composer who had come to St. Petersburg to study at the Conservatory. This sonata was written right around the time of his graduation, and his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov seems to have sponsored it as suitable for Belaieff’s publishing program. Vītols was 22.

Google translates Jāzeps Vītols from the Latvian as “Joseph Willow.” A lovely name.

This sonata has been commercially recorded just once, on an obscure Soviet-era Latvian vinyl record that never made it to CD: Daina Vīlipa (60s?). However, there is an unreleased recording on Youtube, posted by the official account of Latvian pianist Vilma Cīrule (I, II, III), which someone later compiled into a single video synced to the score.

That 19-minute performance is pretty soggy and unfocused, but at least it allows the piece to be heard. I considered posting my own performance to show what I think could be made of the score, but I still don’t have a way of making good clear recordings from my keyboard, and in any case the piece has some difficulties — lots of full-arm leaps, and fancy fingerwork in the last movement — that I’m in no position to play accurately without a lot of practice that I don’t want to do.

It’s not too hard to see that the piece is a student work, with some imbalances and loose ends and needless infelicities for the pianist, but it is also quite charming and surely doesn’t deserve to be so completely forgotten. When I first encountered it, it immediately called to mind the early Medtner sonatas and the first Prokofiev sonata, and I see that Richard Taruskin identifies it as one of the pieces that Stravinsky referred to when composing his student sonata. So it seems like maybe this piece was somewhat prominent for a little while, at least in Russian circles. It’s noteworthy that it’s the only “Sonata” in the Belaieff catalog until Scriabin’s first sonata, published 9 years later. In that context, perhaps this was an assertively Germanic thing to be writing, for Vītols in 1885.

I like how the first movement has a properly stern and declamatory opening theme, but almost immediately betrays its real personality, which is much more interested in being meandering and warm and conversational. These two attitudes never come anywhere near being integrated or reconciled to one another, but maybe that’s the idea. The pointedly brusque and unconvincing ending is like the end of an intractable argument: “Because I say so, dammit!” The second movement is a set of 4 variations arranged for maximum disjuncture: 1. soft, 2. hard, 3. even softer, 4. even harder. I don’t know what the point is, but it does seem to suggest a point, which in itself I like. And the third movement, which is the least well served by the Youtube performance, is genuinely sparkling and charming, in a salon style but raised somewhat above pure superficiality by the thoughtful excursion of the B section. Tricky to play, though.

Another work that has absolutely no reason to be so obscure. It certainly merits a modern recording.

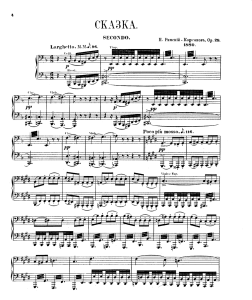

7] Rimsky-Korsakov: Skazka (“Fairy Tale” or “Legend”), op. 29 (1879–80; premiered January 1881)

(н. римский-корсаков : сказка : для большого оркестра : соч. 29)

Conte féerique : pour : Grand Orchestre : composé par : Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow. : Op. 29.

[Fairy Tale : for : large orchestra : composed by : Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. : Op. 29.]

A Mr. Alexandre Glazounow.

• 17 Partition d’Orchestre (1886)

• 18 Parties d’Orchestre (1886)

• 19 Réduction pour Piano à 4 mains par l’Auteur (1886)

A scan of 19, the duet, has been in circulation on the internet since 2004 — very hard to track down who originally uploaded it, at this point — and is now conveniently available at IMSLP. 17 and 18 remain unvailable; IMSLP has a Soviet edition of the full score but it doesn’t use the original Belaieff engraving. The low-resolution image seen below of the title page from the full score was found on the website of the library of Kharkiv, Ukraine.

The prices seen here confirm that this bland monochrome title page is a later reprint. Presumably the original design was in full color, like every other score issued in 1886.

The available pdf of the duet doesn’t include the covers, nor does it include page 3, which apparently contained the following poem as epigraph:

У лукоморья дуб зеленый;

Златая цепь на дубе том:

И днем и ночью кот ученый

Всё ходит по цепи кругом;

Идет направо — песнь заводит,

Налево — сказку говорит.Там чудеса: там леший бродит,

Русалка на ветвях сидит;

Там на неведомых дорожках

Следы невиданных зверей;

Избушка там на курьих ножках

Стоит без окон, без дверей;

Там лес и дол видений полны;Там о заре прихлынут волны

На брег песчаный и пустой,

И тридцать витязей прекрасных

Чредой из вод выходят ясных,

И с ними дядька их морской;Там королевич мимоходом

Пленяет грозного царя;

Там в облаках перед народом

Через леса, через моря

Колдун несёт богатыря;

В темнице там царевна тужит,

А бурый волк ей верно служит;Там ступа с Бабою Ягой

Идет, бредет сама собой,

Там царь Кащей над златом чахнет;

Там русский дух… там Русью пахнет!И там я был, и мед я пил;

У моря видел дуб зеленый;

Под ним сидел, и кот ученый

Свои мне сказки говорил.Одну я помню: сказку эту

Поведаю теперь я свету.А. Пушкин

This is the prologue to Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila (1820). The original Belaieff included this poem in Russian and in a French translation, but the French has not been carried forward to other editions so I can’t include it here. To my great surprise there is no complete public-domain English translation, nor any “standard” English translation, so here’s just my cobbled-together literal nonrhyming line-for-liner:

On curving shore a green oak;

A golden chain on the oak:

Day and night a learned cat

Goes ever around on the chain,

He goes to the right — he begins a song,

To the left — he tells a tale.There are marvels there: there Leshy roams, [Leshy = wood goblin]

Rusalka sits among the branches; [Rusalka = water nymph/mermaid]

There on unexplored paths

The tracks of unseen creatures;

A hut there on chicken’s legs

Stands with no windows, no doors;

There wood and dale abound with apparitions;There at dawn surge the waves

Upon the sandy and barren banks,

And thirty glorious knights

Stride from the clear waters,

And with them their sea-master;There a passing prince

Captures a terrible tsar;

There in the clouds, for all the people to see,

Across forests, across seas,

A wizard bears a hero;

Imprisoned there a princess grieves,

Waited upon by a loyal brown wolf;There the mortar of Baba Yaga [= witch who travels in a flying mortar and wields a pestle]

Goes, moving of its own accord,

There Tsar Kashchei languishes with his gold; [Kashchei = archetypal evil king antagonist]

There the Russian spirit… there the smell of Rus!And there I was, and mead I drank;

By the sea saw the green oak;

Beneath it sat, and the learned cat

To me his tales told.One I remember: this tale

I will now tell the world.A. Pushkin

Now that we’ve read that, the following passage from Rimsky-Korsakov’s autobiography also seems important:

“Strange that to this day the hearers grasp with difficulty the true meaning of the Fairy-tale‘s program: they seek in it a chained-up tom-cat walking around an oak tree, and all the fairy-tale episodes which were jotted down by Pushkin in the prologue to his Ruslan and Lyudmila and which served as the starting point for my Fairy-tale. In his brief enumeration of the elements of the Russian fairy-tale epos that make up the stories of the miraculous tom-cat, Pushkin says

“One fairy tale I do recall, I’ll tell it now to one and all,”

and then narrates the fairy-tale of Ruslan and Lyudmila. But I narrate my own musical fairy-tale. By my very narrating the musical fairy-tale and quoting Pushkin’s prologue I show that my fairy-tale is, in the first place, Russian, and secondly, magical, as if it were one of the miraculous tom-cat’s fairy-tales that I had overheard and retained in my memory. Yet I had not at all set out to depict in it all that Pushkin had jotted down in the prologue, any more than he puts all of it into his fairy-tale of Ruslan. Let everyone seek in my fairy-tale only the episodes that may appear before his imagination, but let him not insist that I include everything enumerated in Pushkin’s prologue. The endeavor to discern in my fairy-tale the tom-cat that had related this same fairy-tale is groundless, to say the least. The two above-quoted lines of Pushkin are printed in italics in the program of my Fairy-tale, to distinguish them from the other verses and direct thereby the auditor’s attention to them. But this has been understood neither by the audiences nor the critics, who have interpreted my Skazka in all ways crooked and awry and who, in my time, as usual, of course, did not approve of it. On the whole, however, the Fairy-tale won sufficient success with the public.”

He needed to write this because the piece sounds so overtly illustrative that of course people wanted to guess at what he had in mind — and this long text printed in the score would naturally seem to be the key! Early on in the piece, he drops in some mimetic bird calls, unmistakable as such, which sure seem to invite the listener to parse the whole thing in terms of specific imagery. The work then proceeds through a series of surprise modulations and explosive outbursts and sudden stark shifts of tone and color, all of which creates the impression of film music without the film. The music seems to be having its strings pulled from offstage by some kind of narrative. It’s only natural to wonder what, exactly, is happening.

Even with all his protesting, I suspect Rimsky-Korsakov did have some specific correspondences in mind, though perhaps non-narrative ones, along the lines of “a theme for Rusalka and the river” and “a theme for Baba Yaga and the forest” and “a theme for brave knights.” Etcetera. I’m not sure what sort of whimsical sprite or grandmother or whatever is being represented by the soft comic interlude with the flute solo, but surely something rather than nothing. For what it’s worth, the whole piece was initially going to be called Baba Yaga. (And was going to be dedicated to Balakirev, but Balakirev didn’t approve of the piece, so the dedication was changed.) I’ve also seen “Overture-Fantasy” as another abandoned title.

The form is odd and disorienting, which contributes to the feeling that one needs a programmatic explanation for the goings-on, but ultimately it does have an internal logic. After some consideration I believe it to be in sonata form, but with a very long and elaborate high-Beethovenian introduction that previews the “second subject” in its entirety, and where the “first subject” — usually the calling card of a piece — is just a not-particularly-tuneful bit of rhythmic galloping material, the least memorable melody in the whole thing.

Speaking as someone who likes listening to film music without films, I’m very happy to listen to this piece a wandering pseudo-narrative score, and not strain to hear the obscure formal scheme. As an orderly overture, the piece isn’t very rewarding, but as a mazy forest, it is. It absolutely sounds like a fantastical folktale, illustrated in rich colors. Getting lost is part of the pleasure, as long as one can relax into that kind of pleasure. I enjoy that Alice in Wonderland feeling of coming round a bend in the path and realizing with surprise that I’ve been here before. Fairy tales ought to feel like being half-lost. That’s the feeling of being truly inside one’s imagination.

Here are 9 recordings. There may be others on vinyl. Average time is about 17 minutes.

Philharmonia/Ansermet, 1946

USSR Radio/Khaykin, 19??

Bochum/Maga, 1977

London/Butt, 1985

USSR/Svetlanov, 1985

Moscow Symphony/Skripka, 19??

Armenian/Tjeknavorian, 1991

Moscow Symphony/Golovchin, 1996

BBC/Sinaisky, 2006

I thought the London Symphony Orchestra/Yondani Butt recording on Youtube was pretty convincing and heartfelt, with vivid color. But they’re all basically okay — yes, even the slow limp ones from the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. A piece to get lost in doesn’t need to be handled with any great finesse. You can get pleasantly lost just staring at a carpet, after all.

Oh, as for the 4-hand reduction, it seems to me nearly impossible to make something convincing from it. It’s no fault of the arrangement; the piece just doesn’t work on a small scale. Everything I’m able to enjoy about it is dependent on being “inside” the swirl of its sounds and colors. Whereas the skeletal impression it makes on a piano is like an object that just sits there, in front of me. Without a way into that illustrated interior, there’s no reason to spend such a long time with these melodies.

8] Glazunov: Serenade No. 1, op. 7 (1883; premiered 1885)

А. Глазунов : Серенада : для оркестра : соч. 7

Sérénade : pour l’Orchestre : composée par : Alexandre Glazounow. : Op. 7.

[Serenade : for orchestra : composed by : Alexander Glazunov. : Op. 7.]

À Monsieur Nicolas Stcherbatcheff.

• 20 Partition d’Orchestre (1886)

• 21 Parties d’Orchestre (1886)

• 22 Réduction pour Piano à quatre mains par l’Auteur (1886)

The full score and the duet are both from Sibley: 20 was uploaded in 2010, 22 in 2007. No parts currently available.

This full score copy has the corrected prices indicating that it’s from later than 1898, whereas the duet has the original prices (with the new price penciled in), and has a catalog from ~1896. Again note that the color printing is a little finer on the older score.

Glazunov is now 18 and is figuring out how to be easy. This piece is a 4 minute bonbon, a song without words. It has three melodic ideas in it, which roll around in rotation a couple times, and then we’re done. And yet even within this miniature the journey isn’t pat; the very slight hills of harmonic tension we go over in the second half are chosen with real art, not just by default.

I am very fond of musical miniatures; I enjoy being able to return over and over to a tiny piece and gradually extract different things from it by letting my imagination grow more and more nuance into each detail. There’s something subtly dreamy about the graceful main theme of this piece that seems to invite me to invest, to look for further meanings on further listens.

Yes, there’s some kind of orientalism going on in the third tune, but my impression is that it’s just part of the Russian nationalist/fantasist default mode and doesn’t signify anything (or anyplace) in particular.

This seems to me a genuinely charming, catchy, eminently successful miniature.

There seem to be 6 recordings:

USSR Radio Orchestra / Nikolai Golovanov 1940s?

USSR Radio Orchestra / Odysseus Dimitriadi 1980

Romanian State Orchestra / Horia Andreescu 1986

London Symphony Orchestra / Yondani Butt 1987?

USSR Symphony Orchestra / Evgeny Svetlanov 1990

Moscow Symphony Orchestra / Vladimir Ziva 2000

I’m able to find something to like in all four of the the available recordings. When a piece is so short, very fine distinctions in the navigation and timbre of each moment feel genuinely significant. Attention expands to fill the space of its subject, so when the subject is small, every detail speaks. These four recordings of a very brief, easygoing, straightforward score end up seeming like remarkably different creatures from one another.

The duet is excellent too — all the charm and subtlety survives the transcription, and the added precision and clarity give it yet another kind of profile. There’s no recording of the duet version but it’s quite as recording-worthy as many pieces written directly for piano 4-hands.

9] Glazunov: Elegy (“To the Memory of a Hero”), op. 8 (1885)

А. Глазунов : Памяти Героя : элегия : для большого оркестра : соч. 8

À la mémoire d’un héros : Elegie : pour grand Orchestre : composée par: Alexandre Glazounow. : Op. 8.

[To the Memory of a Hero : Elegy : for large orchestra : composed by : Alexander Glazunov. : Op. 8.]

• 23 Partition d’Orchestre (1886)

• 24 Parties d’Orchestre (1886)

• 25 Réduction pour Piano à quatre mains par l’auteur (1886)

The duet copy is post-1902; the full score copy is pre-1898, with better color.

No dedication, but we do get this prefatory explanation of the program:

Предисловие.

Автор имел в виду героя идеального, которого жизнь не была ознаменована никакими жестокостями, который сражался только за дело правое — за освобождение народа от притеснения — в мирное-же время наполнял свою жизнь делами правды и общего блага. Смерть этого героя горько оплакивается народом, и его ожидает двоякая слава: слава земная и слава небесная.

Préface.

L’auteur a eu en vue un héros idéal, dont la vie n’avait jamais été souillée par aucun acte de cruauté, qui n’avait combattu que pour la juste cause — cette du peuple opprimé — et en temps de paix avait rempli sa vie d’actes de justice et de bien général. La mort de ce héros est amèrement pleurée par le peuple, et une double gloire l’attend: la gloire terrestre et la gloire céleste.

Google and I translate:

Preface.

The author had in mind an ideal hero, whose life had not been tarnished by any acts of cruelty, who fought only for a just cause — to liberate the people from oppression — and in times of peace filled his life with acts of righteousness and the common good. The death of this hero is bitterly mourned by the people, and a twofold glory awaits him: earthly glory and heavenly glory.

Basically, this piece could be called To the Memory of Obi-Wan Kenobi and Mr. Spock. The horn solo opening is full-on Star Wars. I wonder if John Williams had actually been this way and borrowed a few tricks. (It’s possible, though I think he was more into Elgar.) A 20-year-old composer’s fantasy of an “ideal hero” circa 1885 turns out to be very much in line with our continued understanding of superheroism, much as Strauss’s 1898 Heldenleben still holds up as a comic book ego trip. Our fantasies haven’t actually moved too far in the past century and a half. The only thing that we might feel is missing from Glazunov’s elegy is a tad more testosterone, in the form of, say, a complete Biff Pow battle sequence, reenacting the hero’s feats of combat — which I think is to the piece’s credit, spiritually speaking. There’s no secret fantasy of violence lurking here, or at least it’s lurking very low to the ground. This really is a piece about doing absolute good and being loved and mourned mourned mourned.

Russians seem to love this sort of thing. That Leskov collection featured several “stories of righteous men,” meant to inspire a hot, chest-expanding emotion, the tearful poignancy of goodness.

The two tunes here are very good, solid B+ melodic material, and their initial presentations are, as I say, Hollywood-worthy in their effectiveness. Then there’s a development that starts with a fugato, which is all well and good on the page but I don’t know what I’m supposed to get out of it. This is followed by the obligatory evocation of past struggles (no Biffs or Pows; more like stormy skies and stormy seas) followed by what I guess are earthly glory and heavenly glory in short succession. To me there’s something underpowered about this last section and the way the piece wraps up: we’ve already heard more compelling statements of the same themes, earlier. I think he might have needed to pile on a few more special orchestrational effects to give it the necessary “going to heaven!” lift it wants, so as to be a suitable payoff for the first half. As it is, I think the exposition rather too obviously outshines the rest. But maybe a better performance could change my mind.

I find only three:

Moscow Radio Orchestra / Vladimir Fedoseyev 1980

USSR Symphony Orchestra / Evgeny Svetlanov 1990

Moscow Symphony Orchestra / Igor Golovschin 1996

The Moscow Radio Orchestra recording is, as I’ve learned to expect, quite a bit better than the Moscow Symphony Orchestra’s.

The duet version is reasonable but has, I think, limited potential for performance. It’s a good and playable arrangement of these nice themes, but the overall elegiac pace really requires instruments with expressive sustaining power. A piano is no substitute for a horn solo.

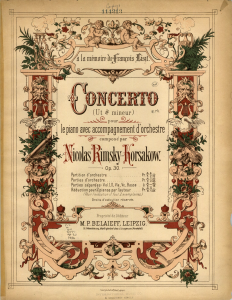

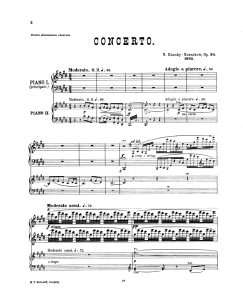

10] Rimsky-Korsakov: Piano Concerto, op. 30 (1882–3; premiered 1884)

Н. Римский-Корсаков : Концерт : для фортепиано : соч. 30

Concerto : (Ut # mineur) : pour : le piano avec accompagnement d’orchestre : composé par : Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow. : Op. 30.

[Concerto : (C# minor) : for : piano and orchestra : composed by : Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. : Op. 30.]

à la mémoire de François Liszt.

• 26 Partition d’orchestre (1886)

• 27 Parties d’orchestre (1886)

• 28 Réduction pour 2 pianos par l’auteur (1886)

26 and 28 courtesy of Sibley, 2012.

This full score is an earlier impression than this piano score, but neither is early enough to have the original prices — i.e. both are 1898 or later.

Here’s the title page from an earlier copy of the piano score (as offered for sale in 2008 by Schubertiade Music) — though still not a pre-1898 with the original prices. This has 5 colors compared to the 4 colors on the copy seen above it. Look how much detail gets lost in the later, presumably more cheaply printed version!

Rimsky-Korsakov composed this concerto at the age of 38. It was premiered by Nikolai Lavrov (1861-1927), a piano professor at the conservatory.

It is a hard piece to hear well, because it calls to mind the pieces it influenced, very much in particular Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, the principal motif of which it shares, more or less. Did Rimsky-Korsakov not think, “boy, this sounds like that famous Paganini Caprice?” I don’t know. Maybe it wasn’t as famous as I think until Rachmaninoff seized on it. Well then, didn’t Rachmaninoff think, “boy, this sure sounds like the Rimsky-Korsakov Piano Concerto!” He probably did. In addition to having the same five-note figure at its heart, the overall emotional gesture of the “sweepingly Romantic” episode in both pieces is rather obviously the same one. In fact it’s hard not to hear the middle of this piece as a precursor to all of Rachmaninoff.

Rather than coming from Paganini, the tune in the concerto — and there’s really only one tune, without any actual contrasting material — is in fact #18 from Balakirev’s collection of Russian folk songs.

I’m led to understand that, as per the dedication, the whole thing is actually rather overtly derivative of the Liszt piano concertos, which I don’t actually really know — I’ve listened to a recording several times but never paid good attention. I recognize the rather indulgent approach to the material as essentially Lisztian: everything, even the form, seems motivated by a spirit of Romantic flamboyance above all. Now, I don’t have the strongest sense of Rimsky-Korsakov — I’m developing it as I go, here — but I think of him as more essentially reserved a personality than Liszt, a builder of fancy toys rather than a fancy toy himself. And to me there’s something a little thin about this piece, as though someone is going through the motions of extroversion without any actual burning need.

The piano part is difficult but only in the most traditional Romantic piano concerto ways — lots of scales, arpeggios, and an avalanche of octaves at the end. All of which feels a little arbitrary. The overall impact of the piece is that something a little arbitrary has just happened.

Ultimately, its themes and its sweep having been thoroughly stolen by Rachmaninoff and its flair being itself stolen from Liszt, this concerto is always going to feel like an also-ran. But it has several very nice moments — I like the spooky cascade of woodwinds first heard about a minute and a half in. The whole introduction seems to promise a very rich experience that never quite arrives, but it’s still a nice introduction. The sweeping high point is good, too.

The piece is about 15 minutes long — short for a concerto, long for a single monothematic movement.

Concertos generally seem to have a better chance of being recorded than other genres, I guess since soloists have some ego-incentive to root around for underplayed repertoire that they can claim as their own. Since this obscure concerto is by a name composer, there are a bunch of recordings. Here are the 11 I came across without trying very hard:

Sviatoslav Richter, Moscow Youth Orchestra / Kirill Kondrashin 1950

Lev Oborin, USSR State Symphony Orchestra / Nikolay Anosov 1952

Sergio Perticaroli, RAI National Symphony Orchestra / Massimo Pradella 1961

Michael Ponti, Hamburg Symphony Orchestra / Richard Kapp 1972?

Igor Zhukov, Moscow Radio Orchestra / Gennady Rozhdestvensky 1972?

Malcolm Binns, English Northern Philharmonia / David Lloyd-Jones 1992

Geoffrey Tozer, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra / Dmitri Kitajenko 1993

Jeffrey Campbell, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Gilbert Levine 1996

Noriko Ogawa, Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra / Kees Bakels 2003

Hsin-Ni Liu, Russian Philharmonic Orchestra / Dmitriy Yablonsky 2006

Oleg Marshev, South Jutland Symphony Orchestra / Vladimir Ziva 2007

I haven’t listened to them all. Richter is famous but the sound isn’t great. Ponti is good. Zhukov seems good too.

So far you may be getting the impression that the Belaieff catalog is 1) mostly orchestral works, 2) mostly works by reasonably famous composers, 3) mostly recorded at least once, 4) mostly available scanned online. None of these four things is true! As will become clear if I continue this into the next 5 items. And there’s every indication that I will.

Is the R-K Fairy Tale duet worth learning?

D

Also…. Glazunov duets?

D

Of the pieces I’ve posted so far, I’d say the Glazunov Symphony No. 1 and Serenade op. 7 have the most effective 4-hand arrangements, and merit performance. The “Memory of a Hero” op. 8 I’m a little more skeptical about, like I said. (The two Greek Overtures seem like they’d be pretty good but unfortunately those duets haven’t been made available, that I know of.)

The Rimsky-Korsakov Overture op. 28 and Fairy Tale op. 29 both seem to me too longwinded and dependent on orchestral color to come off well on just a piano, but I guess I could be proven wrong. I played them both against my own recorded self, and struggled a lot trying to make them at all convincing.

I’m pretty sure you have at least some of Rimsky-Korsakov’s duet arrangments in a Belwin Mills reprint volume on your shelf. Go check.