2000:  2008:

2008:

written and directed by Agnès Varda

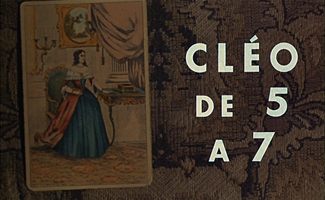

Criterion #73: Cleo from 5 to 7.

(The second, current edition only exists as a component of boxset #418 “Four by Varda,” but it retains the original spine number 73.)

One of the bonus features on the disc is a 1958 short film by Varda, L’opéra Mouffe, which centers around vérité footage of hard-looking elderly French people going about their shopping at an outdoor market. The documentary images are casual but pointed, quick keen sideways glances at real life. Many of the shots end just after the subject notices the camera and eyes it with suspicion for a moment.

Stuff like this gives me immediate access to the creative mindset that generated it: I’m very familiar with that good lively feeling of being alert to what’s going on around me, and to the potential cinema formed by my glances. In those moments it seems so simple. My existential window on reality is its own work of art already; it would only need to be captured, as-is.

But I’ve encountered many works of art made in this spirit and generally they fail. The documentary vitality, when it survives at all, usually just ends up exposing the needlessness of the work itself: “Yeah, this does kind of remind me of the feeling I get when life inspires me to make something, which is exactly why it’s such a waste of my time and attention to watch this fartsy assemblage of nothing-in-particular.”

What impressed me about L’opéra Mouffe was that Agnès Varda had actually managed to make something real and personal and worthwhile out of that kind of inspiration. “Oh, that feeling can go somewhere!” I thought — which was a happy thought, as you can imagine.

The observational core of L’opéra Mouffe is stolen footage of real people going about their business, but the film is not only that: it is cut together with music and staged scenes and invention of various kinds, sentimental and whimsical and symbolical and otherwise, and the whole is presented as the artist’s musings on the occasion of her first pregnancy. On paper that sounds extremely female in form and content, which I suppose it is, but often with the poem/diary works of female artists I end up alienated by too-private symbols, whereas this was thoroughly communicative.

Varda’s attention feels complete and uninterrupted. She is equally attentive to her dream and her reality, and to the thing she has made by juxtaposing them, the film itself. This, I think, must be the key to making good on one’s spark of documentary inspiration: remain just as attentive, just as open to experience, even after the moment of inspiration! If you are going to render your point of view into art, you must remain completely aware during the entire process, even as that process inevitably changes what it is that one is aware of. Keep attending to what’s actually going on, or you will betray your real purpose and the art will die. Too often — almost always! — vérité is actually a kind of counterfeit attention, a way of aping and alluding to actual attention, which fled at the approach of the artist’s ego. Somewhere between the moment of inspiration and the final product, most artists stop being open and start demonstrating that they are being open, that they were once and in fact still are very inspired and open — which at that point is no longer true.

But somehow Agnès Varda has her psyche in order and manages to stay honest and alert, and it shows. In the bonus documentary that she put together for the disc (in lieu of a commentary), she informs us that in preparing the new transfer, she took the liberty of making a tiny edit, shortening two consecutive shots by about a second-and-a-half total because it struck her that they would flow a little better. The excised second-and-a-half is shown in the documentary so that we don’t feel cheated, and so that we can consider the subtlety of the rhythmic difference. It is supremely subtle. Unlike every other decades-later “director’s cut” edit I’m aware of, it was not done to settle an old score or change some discrete conceptual element; the edit is a genuine artistic tweak, the result of that continual openness to the work on a musical level, a poetic level. I don’t think most directors would be capable of even conceiving of such an edit to an old film, except as a kind of boast. I didn’t get the slightest impression of boastfulness in Agnès Varda’s personality in the interview footage on this disc. She seems very warm.

This has all been said so that now I can say “and the feature is like that too.” Cleo from 5 to 7 also has quite a lot of stolen Parisian street footage in it, with people glancing warily at the camera or with surprise at the unlikely glamour of Corinne Marchand strolling by. It’s so fully made a thing, scripted and acted and constructed, that at first it’s not nearly as obvious that it flows from that feeling of “Life is art already, just look at it!” But that’s a sign of it being so full a realization of that inspiration. Instead of reminding me of what it’s like to want to make art, it is itself a piece of art.

I don’t want to compare everything to Ulysses, but there is sort of a female take on Ulysses going on here. The city, the day, the hours and the minutes, these are aesthetic enough as they stand, without interference: a universe of endless aesthetic truth — against which one person’s life, any person’s, can never be fully Romantically consequential, even if it is deeply sympathetic.

An interesting thing about this movie is that despite having that kind of universalizing framework, its protagonist Cleo is not a traditional everywoman as you might expect — in fact she’s a sort of celebrity, a pampered pop singer and a glamour girl, the only person in her world with movie-star looks. And there’s no denying that the movie deliberately trades on having a pretty woman on the poster and in every shot. Yet it’s still an everywoman artistic construction Cleo is inhabiting. Her progress is to gradually shed some of her bubble of glamour until she touches down on human contact at the end… but of course the glamour never goes away because it’s a movie!

Is the movie chiding us for envying the beautiful people, or is it saying “spoiled beautiful people are still people underneath,” or is it only half “problematizing” her looks (insofar as they’re written into the plot) and half genuinely reveling in them, as nouvelle vague chic? Or something else? I don’t know, but I find it a stimulating uncertainty.

At the beginning, beset with morbid anxiety, Cleo looks in a mirror and thinks to herself, “As long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive more than others.” The feminist thrust of the script eventually makes clear that Varda sees this as a kind of oppressive role-playing that keeps Cleo from her real self. But at the same time, the film is a film, it’s a visual and magical reality, and in its terms, there is something very true about what Cleo has thought: her beauty is equivalent to life, in the purest cinematic sense, in the mind of the movie-watcher. Look at the box art! And I think Varda knows this, or at least is sensitive to it. So there is a kind of philosophical ambiguity to the whole thing even after one has seen it all and heard the official line.

Another one of the bonus features is a clip from 1993 with Madonna (!) and Varda appearing together on a French interview show. Madonna says she had at one time been interested in doing a remake of this movie. This feels fairly absurd on the surface of it, but I can understand why this movie would appeal to her. There is a Madonna-like ambivalence in it about the significance of constructed identities and of being attractive; the movie basically is about how it’s not real to be chic and attractive, but of course one must be the most attractive person in the universe to have the opportunity to learn this lesson good and properly. Because lessons are for protagonists, and we all know what protagonists look like.

The last section of the movie is Cleo finding a real human connection with a soldier who shows up and starts talking cheerfully and openly with her. But we must also be aware, as she is aware, that what he is doing is hitting on her, that he has approached her for superficial reasons like anyone else, and that this cheerful openness is his tried-and-true way of endearing himself to chicks. That doesn’t preclude its being genuine or human. That’s the complexity of the movie. Despite the feminist undercurrents, it does not actually offer its protagonist any real break from her world of chilly, brittle sex appeal. Not even at the very end, I think. It’s only an hour and a half of her life, after all!

(The title is a play on what is apparently a standard French insinuation about men meeting with their mistresses from 5 to 7; the actual 90-minute movie only runs from 5 to 6:30.)

This brings to mind the thing that Kenneth Lonergan said about You Can Count On Me: that in real life, people don’t generally change very much or very quickly, so for a person to change even a little bit in the course of a movie should be portrayed as a big deal. This movie ends where that one did, with a glimpse of the potential for change rather than change itself.

Cleo has a freer-spirited friend in the movie, first seen modeling nude at a sculpting studio. Cleo says she could never model nude, that she would worry about the artists finding faults. The friend says: “Nonsense! My body makes me happy, not proud.” This I think is the moral of the movie: life should make us happy, not proud — as should youth and beauty and health, if applicable. This is also, probably, the answer to any questions about why this movie can be rather arbitrarily about a head-turning Hitchcock blonde and still be feminist: because real life is all-inclusive.

Of course, it’s not actually a movie with a moral. It’s that spirit of observational inspiration — of thinking “hey look, the world is already a movie, going on right now” — spun out as it rarely is, into a genuine work of film art. One is drawn into its circle of sympathy and ends up looking at it just the way the model says she feels the sculptors look at her, beyond any vanity. I enjoyed its humanity and openness, and did not find faults, because I wasn’t seeing it that way.

(Well, except… the one and only quibble I had was with the incongruous indulgence in the middle when Cleo and her friend watch a twee little silent short that Varda made with her rather famous friends. This pulls you right out of the flow and forces you to think about “Agnès Varda” and the historical moment, which is really the last thing you want in a movie. Luckily it’s brief and can be more or less overlooked.)

Connection to the preceding: a guy plays at an upright piano while chatting with the heroine. I mean, there’s plenty of dull stuff: driving around Paris, black-and-white, singing, whatever. I’m probably missing a really good one, though.

Yeah, the movie’s black-and-white. The title screen above is a fake-out: only the opening tarot card sequence is in color. Agnès Varda gives a pat explanation for why this is so, but I’m not sure her reason for doing it is the reason that it works. But it definitely works wonderfully. Besides the fact that a tarot reading is a great opening for any movie, the sudden cut from seductively cozy Wes Anderson tabletop color close-ups to uneasy black-and-white faces creates a very powerful philosophical jolt right at the outset, which throws one’s doors very wide open to whatever will follow.

Actually, that’s kind of the same as what Agnès Varda says about it, isn’t it. I guess she was right after all.

Music is by Michel Legrand, who shows up in all his 1962 youthfulness as “Bob the songwriter” and fools around at the piano in Michel Legrand style. Then he hands a new song to Cleo and she sings it in a sequence that is obviously the musical centerpiece of the movie — the piano accompaniment gradually fills out with full orchestra — but can’t be my choice here because it’s a song and I don’t do songs. (The backing track for the song actually recurs later without the vocal, but I still can’t use it because there it’s covered with dialogue.)

Our options for unobscured music are in fact very limited: we basically have to go with the short cue that brings us into Cleo’s world immediately after the title sequence, at the start of Chapter 1, as she goes down the stairs and then out onto the street. I have omitted a couple of lines in the gap between the two parts so that we can listen to more than a minute of uninterrupted music.

Michel Legrand might have written “the circle of fifths” again and again throughout his career, but he had a real feeling for it. He was never phoning in the circle of fifths; he always meant it. This bare little cue, which seems to have been conceived mostly as something that could sync to her footsteps, turns out to be very effective stuff.

It doesn’t take much to do good work; you just have to mean it!