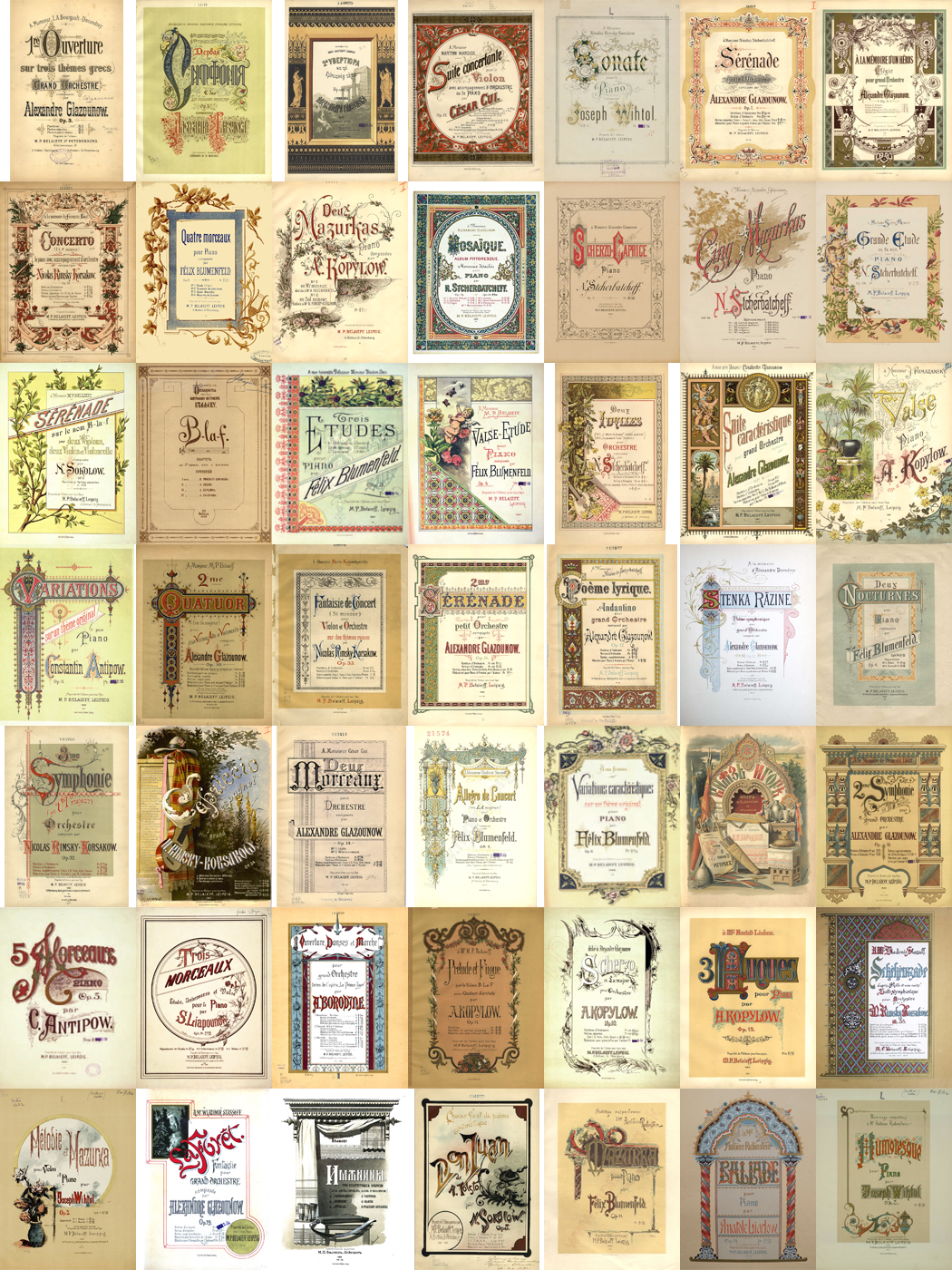

I continue to be keeping the antlike part of my mind arbitrarily busy with the Belaieff catalog while I relax, meditate, what-have-you, so here’s some more grist for the ol’ broomlet.

Obviously, going through them in order occurs to me. I guess I’ll do 10.

Having done 5, I say: 5 turns out to be a lot! Let’s just do 5 for now.

Hey readers: please click on the title of this entry above (“First 5 from Belaieff”) and go to the dedicated entry page. On the front page, the width is too narrow for the images etc., because of the sidebar. I’ll get that fixed one of these days.

1] Glazunov: Overture No. 1 (on Three Greek Themes), op. 3 (1882)

1ая Увертюра : на три греческия темы : для большого оркестра : сочинение Александра Глазунова. Op. 3.

1re Ouverture : sur trois thèmes grecs : pour grand orchestre : composée par Alexandre Glazounow. Op. 3.

[1st Overture : on three Greek themes : for large orchestra : composed by Aleksandr Glazunov. Op. 3.]

A Monsieur L.A. Bourgault-Ducoudray.

• 1 Partition (Full score)

• 2 Parties séparées (Orchestral parts)

• 3 Piano à quatre mains (Arrangement for piano four hands)

Only the full score, with plate number 1, is currently available, having been digitized in 2009 by the Sibley Music Library at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester, superstars in this game and henceforth to be referred to as “Sibley.” Orchestral parts tend not to be held by university libraries and are far less likely to have been scanned or even included in searchable catalogs. The 4-hand arrangement, plate number 3, is out there in Worldcat, just not online.

Here we see the outer cover, title page, and first page of the full score. Click any image for the big version.

According to a Belaieff pamphlet, this, their very first publication, appeared on July 11 (old June 29), 1885. The next many scores that follow are all marked as having been published in 1886, so it seems that this one stands alone and was followed by a full year’s delay before things really got rolling. The title page doesn’t yet mention Leipzig, and instead seems to have been produced in collaboration with the existing Rahter/Büttner firm. Arrangements had yet to be made.

The Overture Op. 3 was composed in 1882 when Glazunov was 16 or 17, premiered in January 1883 by Anton Rubinstein, and then possibly revised for publication. It was upon hearing this and the two pieces that follow (opp. 5 and 6) that Mr. Belyayev decided to spend the rest of his life pouring his enormous fortune into the performance and publication and cultivation of new Russian music. He and his father before him had made their money in the lumber business; Scheherazade was funded by many acres of wood. Somehow that feels right to me. Whereas if it turned out he was in the rifle business that would be dismaying. (Or the laxative business.)

I count at least 5 recordings:

– Minneapolis/Mitropoulos 1942

– USSR/Gauk 1950s?

– Hong Kong/Schermerhorn 1984

– USSR/Svetlanov 1990

– Moscow Symphony/Ziva 2000

I haven’t heard the Svetlanov, but I didn’t find any of the others particularly satisfying.

On paper and in my imagination, the piece seems potentially perfectly effective, as long as one finds the proper spirit of fun in indulging the faint, generic exoticism of its “Greek” materials. The three themes are taken straight from 30 Mélodies Populaires de Grèce et d’Orient, a collection assembled by Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray, the dedicatee, wherein they’d already been fairly de-ethnicized and squared up. See nos. 1, 20, and 25, in that order.

The trick to performing this kind of music — and “this kind of music” encompasses nearly everything that’s going to follow, too — is to take it seriously without taking it seriously. The crucial nuance is attitudinal rather than strictly musical. It tends to be a dimension of performance that conductors can’t control through any amount of pep-talking or careful rehearsal. Only by force of personality, if at all. What I’m talking about emanates from the social culture surrounding the music, not from the technique; it’s in the players’ subconscious.

At nearly 15 minutes with nothing particular to accomplish, this piece threatens to feel overlong, so I don’t understand why all the recordings insist on taking the slow theme so emptily slow and pseudo-ominous. Seems to me the exposition of all three themes should strive above all to be songlike, hummable, at whatever tempo that entails, and then the development that follows should strive to very explicitly spin out a series of miniature compositional clevernesses (rather than try to actually sell “stirring” or “angsty” in a boring Hollywood/operetta way). And keep it all breezy!

If the 4-hand version were available I’d slap down my own take along those lines. I just hummed my way through it and came out at 11:30. That’s more like it!

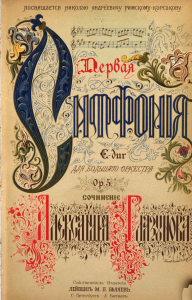

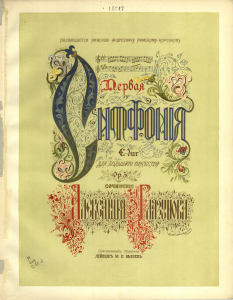

2] Glazunov: Symphony No. 1, op. 5 (1881)

Первая Симфония : (Е-дир) : для большого оркестра : Op. 5 : сочинение Александра Глазунова

Première Symphonie : (Mi majeur) : pour grand Orchestre : Op. 5 : composée par Alexandre Glazounow

[First Symphony : (E major) : for large orchestra : Op. 5 : composed by Aleksandr Glazunov]

посвящается николаю андреевичу римскому-корсакову.

[Dedicated to Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov.]

à Monsieur N. Rimsky-Korssakow : Hommage affectueux de son élève reconnaissant.

[to Mr. N. Rimsky-Korsakov: affectionate tribute of his grateful pupil.]

(A fuller dedication appears inside, reproduced from Glazunov’s handwriting. I think it says:)

Дорогому учителю моему Николаю Андреевичу Римскому-Корсакову в знак глубокого уважение и благодарности.

[To my dear teacher Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov as a token of my esteem and gratitude.]

• 4 Partition d’orchestre

• 5 Parties d’orchestre

• 6 Réduction pour Piano à quatre mains par Mme. Nadejda Rimsky-Korssakow

4, the full score, comes to us from the Harvard libraries, scanned by Google in 2007. 5, the orchestral parts, is currently unavailable. 6, the duet, is from Sibley, scanned in 2011.

These scores were first published in 1886, but the covers seen here indicate that these particular copies are from later: these type styles weren’t adopted for some years, and the Belaieff catalog listing on the inside and back covers (not seen above) makes clear that each of these was issued in 1902 or later. (Note also that the full score identifies itself as the Nouvelle edition revue et corrigée par l’Auteur. I’m not sure when that was added.)

The question then follows: are the title pages seen here in their fullest and most lavish forms? I ask because it seems that after about ten years — once it became clear that his publishing scheme was going to continue indefinitely — Belaieff started to scale back some of the opulence, and would do things like reprint old title pages with simpler color schemes, or previously multicolored title pages in monochrome.

But these are quite multicolored and come off as fairly luxurious, so I assume they’re the full-fledged originals. This is one of the very few of these illustrated title pages to be signed by the artist: “Рисов. Ольга Глазунова” = “Drawn by Olga Glazunov.” Is this the composer’s sister? Mother? Cousin? I can’t find a source to tell me anything about his family or their names. As far as I can tell, Glazunov has never received a book-length biography in English, nor have his memoirs been translated.

The two snippets of music included in the design are themes heard in the second and fourth movement, which reportedly are Polish folk tunes that Glazunov heard his family’s gardeners singing.

Added 6/1/15: I’ve just found that the Russian State Library has scanned a copy of the full score with the original 1886 cover, albeit only in black and white:

The work was composed in 1881–2 when Glazunov was 15 and 16, and premiered in March 1882 to considerable acclaim and prodigy-hype: “can you believe a kid wrote this?” It’s generally described as having made a splash that launched Glazunov’s long career. Basically, by so impressing Mr. Belaieff, it set Glazunov up for life.

It’s about 35 minutes long and I count at least 8 recordings:

– Moscow Radio/Fedoseyev 1981

– Bavarian Radio/Järvi 1983

– USSR Ministry/Rozhdestvensky 1983?

– USSR/Svetlanov 1989

– Moscow Symphony/Anissimov 1995

– BBC Wales/Otaka 1997

– Russian State/Polyansky 1999

– Royal Scottish/Serebrier 2009

(“By some estimates, Moscow has up to 40 orchestras,” each of which has had many different names over the years, and all of which have basically the same names as each other. Plus the conductors have bounced from one to another. Probably so have the players.)

None of what I heard was completely ideal, but to my ears the Fedoseyev recording was the standout for vigor and commitment. People online seem to really like the Serebrier but I thought it was trying much too hard, distorting things to try to “make a case for them,” which of course implicitly makes the opposite case. Who says this music needs help?

The piece is pretty good, earnest and straightforward and fully colored. The sturdy sonata-allegro movements, the first and last, seem to me the most successful. The Scherzo has rather lame material that would require extremely spicy treatment to work, but apart from a wah-wah-wah sad doggy joke toward the end, Glazunov just does standard peasant dance stuff, and the fun feels feigned. The Adagio doesn’t really ever sink its teeth into the emotion it’s going for. I have enough composerly experience to know that this sort of sustained, fluid elegiac expression is actually the hardest thing to craft. A convincing slow movement requires the greatest possible control and boldness, and that’s the movement where it’s easiest for me to imagine the composer as being only 16. But a very, very ambitious 16! The guts it takes to write a thing like this! The fact that the slow movement doesn’t completely land just accentuates how daring he was to risk it at all.

Of course, daring and ambition is different from having anything to say. My impression during the middle movements is just the kind of thing that has tarred Glazunov (and this whole generation of Russians) generally, which is that he seems more proud of his skill than interested in his feelings. That isn’t always necessarily a problem: after all, pride is a feeling too, and a good one. In the first and last movements here, I feel like that pride becomes contagious, to the music’s great credit. But it does become a problem when the ostensible subject of a piece is another feeling not compatible with pride: such as e.g. the urge to carouse (I don’t believe he’s feeling it) or a hovering melancholy (I don’t believe he’s feeling it).

Or rather, I do believe he’s feeling it, but I don’t believe this music has any direct line to the feeling.

Within the next 15 years Glazunov would get enormously fat and become a terrible alcoholic, both of which states would persist for the rest of his life. I have to assume his alcoholism was related to some kind of emotional repression, and I imagine I can hear the seeds of it in this very early work. Building fake emotions to speak on behalf of real ones is a dangerous practice.

Mrs. Rimsky-Korsakov’s duet arrangement is very smartly done. It’s a genuinely performable score, not an unpianistic mess as these things sometimes are. It even sounds pretty good. It could probably be pulled off for an audience — i.e. not just for the amusement of the players. That’s a lot to do with the nature of the piece, which is mostly rhythmic and strongly outlined and suited to being banged out on a piano; subtleties and slow movements never really come off very well in this form. Though I think you could even make something reasonably inoffensive of this slow movement on the keyboard if you sped it up a bit. In fact, lowering the stakes, so to speak, by transferring the music to the quieter, more intimate headspace of the piano, might actually help the movement.

3] Glazunov: Overture No. 2 (on Three Greek Themes), op. 6 (1883)

2я увертюра : на три греческия темы : для оркестра : сочинение александра глазунова. Op. 6.

2me ouverture : sur des thèmes grecs : pour grand orchestre : A. Glazounow : Op. 6

[2nd Overture : on (three) Greek themes : for (large) orchestra : by Aleksandr Glazunov. Op. 6.]

посвящается милию алексеевичу балакиреву.

[dedicated to Mily Alekseyevich Balakirev.]

• 7 Партитура / Partition d’orchestre

• 8 Оркестровые голоса / Parties d’orchestre

• 9 Переложение для форт. в 4 руки автора / Réduction pour Piano à quatre mains par l’auteur

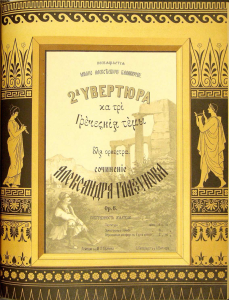

7, the full score, was scanned by Sibley in 2009; the parts, 8, are unavailable. 9, the duet, is also unavailable but its title page, as seen below, is included as a sample on the website for The Beauty of Belaieff, a coffee-table book representing the collection of Richard Beattie Davis. As you can see, it’s a crop and slight lateral stretching of the same illustration.

Actually, I get the impression that the illustrations were squished horizontally to fit the tall narrow layout of the orchestral scores, and that the wider piano editions are the ones that show them in their original proportions. But that’s just a hunch.

It’s not clear whether the front cover seen here (as a black-and-white scan) is original to 1886 or not. It has what I believe is the earliest type style.

The piece seems to have been composed in 1883 immediately after the previous Overture on Greek Themes, on exactly the same model, and premiered only a couple months later, in March 1883 (conducted by Balakirev, the dedicatee). Three themes have again been selected from that same collection, this time nos. 5, 7, and 24. Again he uses them in the order they appear in the book!

However, this is a markedly more nuanced and mature work than the first overture. In part it’s because the themes he chose are themselves subtler and more oblique, with rhythmical evasions that lend themselves to rhapsodic treatment — but he also handles the materials with a much greater license and willingness to create moods and events that are completely his own.

Contrary to the “everything Greek I can think of” title page illustration, the piece isn’t nearly as starkly exoticist as its predecessor; apart from a string of standard “rustic” effects in the second theme, its fantasy-nostalgia is mellower and more general. I think the handling of the opening idea in particular is excellent and affecting, and when it recurs toward the end, there’s the feeling of a real operatic drama coming to fruition. I said that the first overture had nothing much to get done during its 15 minutes; this one feels like 19 minutes worth of drama, though I couldn’t tell you quite what the drama is.

The unpredictable handling of form here is quite impressive, to me much moreso than anything in the rather square-headed Symphony. I wish the duet version were around so that I could play through it and discover its ins and outs for myself.

Well, I just followed it through with the full score, which will have to do. Turns out that despite seeming “unpredictable” to my ear, the piece actually has basically the same underlying form as the first overture. It’s just that the proportional emphasis on the development, and especially on the elaborate coda, has been so much increased as to make it feel like a whole different beast. That, to me, is how form should work — as a tool for the composer, not a prescription for the audience experience. Yes, the journey of this piece is in its broadest outlines a “sonata form” journey — i.e. exposition, conflict, denouement, conclusion — but such a heavily inflected version that, from my point of view as a listener, it may as well not be built on an actual sonata form. After all novels and dramas follow the same general structure and certainly aren’t “sonata forms.”

But it turns out on inspection that it is in fact a sonata form. Because that’s just how someone like Glazunov thinks and works.

A few years ago I stole a choice measure-and-a-half from the introductory section of this piece and put it in a piece I was writing. Nobody knows this piece. Of course, nobody knows my piece either. The perfect crime!

About 17 minutes long. I’m aware only of three recordings:

– USSR/Gauk 1950s?

– Hong Kong/Almeida 1986

– Moscow Symphony/Ziva 2000

I actually quite enjoy the slow lushness of the Ziva recording, though there are places where I find myself leaning to try to make it different.

4] Cui: Suite concertante, op. 25 (1884)

ц. кюи : концертная сюита : для скрипки : с сопровождением оркестра или фортепиано : соч. 25

Suite concertante : pour le Violon : avec accompagnement d’orchestre ou de piano : par César Cui. : Op. 25.

[Suite concertante : for violin : accompanied by orchestra or piano : by César Cui : op. 25.]

A Monsieur Martinn Marsick.

• 10 Partition d’Orchestre

• 11 Parties d’Orchestre

• 12 Pour Violon avec accompagnement de Piano (copy 1, copy 2, copy 3)

• 471–474 (= the individual movements from within 12, made available separately around 1892)

• 556 No. 3. Cavatina, arrangée pour Violoncelle et Piano (also issued around 1892)

• 4054 (= 10 as reissued in 1983)

10, the full score, is available courtesy of the Russian State Library (RSL); the 1983 reissue is available at IMSLP. The parts, 11, are unavailable.

12, the violin and piano version, is available in three copies: two from Sibley and one from RSL.

556, the cello arrangement of the “Cavatina,” is known only from the Belaieff 1902 catalog and does not appear in Worldcat, so it must be pretty rare. The arrangement does seem to have turned up in a few cello albums from other publishers over the years.

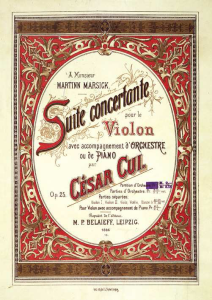

Title page x2 and first page of the full score. The first title page is a hi-res B&W scan from RSL; the second is a lo-res color scan from the Beauty of Belaieff site. (Note that the color copy is a later version; the reference to Büttner has been dropped and the plate number has been added.)

Title page and first page of the violin and piano score. This title page comes from the first Sibley copy, which has catalog text placing it between 1895 and 1902. (Note that the piano version cuts straight to the tune and doesn’t include the orchestral introduction seen in the full score above.)

Cover (B&W scan) and title page from even later copies of the violin and piano score. This title page comes from the second Sibley copy, which has catalog text placing it after 1902. Note the slightly different color contrast; the chromolithography technique seems to have gotten just a tad harsher, less luxe. Hasn’t it? I suppose that may be an artifact of the scanning but I don’t think it is; I think some money is being saved somewhere. I can’t blame them. It still looks pretty damn fancy.

The changes in the prices between the second title page and the third may be beyond my ability to interpret but here’s my attempt. I’m assuming the M above the line is Marks, and the R below is Rubles. This seems confirmed by the “Pf.” over “Cop.” for the cheapest items: “pfennig” and “copeck,” I take it. What we see here is that from 1886–1895, everything cost exactly twice as many marks as rubles, but after 1902 or thereabouts, a mark has dropped to be 7/20 of a ruble (from 10/20). Since the printing is all done in Leipzig, the German price of the full score stays fixed and the Russian price drops.

But at the same time, the prices of all the piano versions drop in both currencies, and not by a consistent percentage or amount. It seems they’ve just been repriced, I guess to accord with some new sense of the market. The price of a complete set of parts has also dropped. And yet the price of individual parts has not; it has stayed the same in terms of kopecks, and so has actually risen in terms of marks. I can’t come up with a theory to explain that. Try your hand at it.

Cui was of the older “mighty handful” generation and was 49 when he wrote this. I can’t confirm that it was premiered by Marsick, the dedicatee, but it seems likely. I found a reference to Marsick performing it in Moscow in December 1885; it seems possible he had been there to premiere it the previous year.

The piece is complete 100% crowd-pleasing “pops” material. Sounds good to me. In fact this piece lays out the terms of what I think ought to be the standard middlebrow contract with the audience: utter directness without pandering. I never get the sense of Cui writing “down” just as I never get the sense of him writing “up.” The piece achieves not just tunefulness but a being at home within tunefulness that is actually more valuable than the tunes themselves. The tunes themselves are perfectly fine (if not overly remarkable) exemplars of a high craft of melody-spinning that hardly even exists anymore. What puts me at my ease listening to a piece like this is the mere fact of dedication to that craft, far more than any particulars of what the craft has generated. It feels like the same thing as dedication to friendly conversation, or to ease, or to good cheer. A good party isn’t one where people necessarily say memorable things, it’s one where people all tacitly and mutually agree that it’s a good party, and share a sense of what that entails. That there is so much that is tacit and mutual about the culture of salon art — which is what the Belaieff catalogue ultimately is — to me can only ever be a positive thing. I just don’t see any value in marking it up with socio-political annotations. I may not be a rich 19th century St. Petersburger, but the music is treating me like I am, so what’s to complain about?

I’m aware of only one recording, of 21 minutes: Nishizaki, Hong Kong/Schermerhorn 1984. This is perfectly passable and listenable, especially in the middle two movements, which seem to be easier. The ensemble gets a little ragged in the first movement, and the last movement could stand a good deal more atmosphere and drama, not to mention flair. Nonetheless, I appreciate that in their unimaginative approach, these players have hit on basically the right attitude: “this music works, so we’re just going to play it.” They play it like a pit orchestra, which is to say like players who are relaxed because they know the attention is elsewhere. All musicians should be so relaxed!

I see no reason why this suite shouldn’t be programmed at minor pops concerts the world over, all the time. As far as I know, it’s not.

The piano version is playable enough and I’m sure one could sell it at a violin recital but I’m not sure I buy it as a fully equal alternative, as suggested on the title page (“accompanied by orchestra or piano”). In its slick suavity, this feels like a fundamentally orchestral piece.

5] Rimsky-Korsakov: Overture (on Three Russian Themes), op. 28 (1866, rev. 1879–80)

н. римский-корсаков : увертюра : на темы трех русских песен : для оркестра : соч. 28

Ouverture : sur des thèmes russes : (Re majeur) : pour Grand Orchestre : composée par : Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow. : Op. 28.

[Overture : on (three) Russian themes : (D major) : for (large) orchestra : composed by : Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. : op. 28.]

A Mr. Anatole Liadow.

• 10 Partition d’Orchestre

• 11 Parties d’Orchestre

• 12 Réduction pour Piano à 4 mains par l’auteur

10 was digitized at Harvard by Google in 2007. The complete parts, 11, are in fact available in this case, at least in the form of a Kalmus offset, which someone scanned for IMSLP in 2013. The duet arrangement, 12, is not currently available online in its original Belaieff edition, but I was also able to find a scan of a Soviet edition posted to the Pianophilia forums.

Often, as here, Google book scans have been subjected to a harsh auto-white-balancing that may have drained some of the legitimate color, and possibly even some detail. For now, this is all we’ve got. Once again, the catalog copy indicates that this particular printing is from after 1902.

Grove describes this overture as “a faithful copy of Balakirev’s work of the same name,” which dates from 1858. I appreciate the tip. They’re right!

The first version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s overture was composed in 1866 when he was 22 (and Balakirev was 29), but unpublished until the Soviet era. The present, second version was revised in 1879–80, when Rimsky-Korsakov was 34–5 and had worked his way to opus number 28. I don’t have access to the score or recording of the first version so I don’t know how different it is, but I’m curious. Interestingly, Balakirev seems to have then gone back and revised his Overture on Three Russian Themes the next year, in 1881.

Richard Taruskin calls the Rimsky-Korsakov overture “practically a plagiarism” of the Balakirev, but apart from a few strikingly similar passages (including the very opening) that’s not really fair — the two pieces are distinguishable not just in materials but in character. And I’m not sure the comparison flatters Rimsky-Korsakov, despite his being generally considered the far superior composer. Balakirev’s piece at least gives an engaging impression of wildness, where Rimsky-Korsakov tends to iron out even his most striking inventions by dutifully repeating them. Balakirev’s piece is about 8 minutes long and Rimsky-Korsakov’s is 12 or 13. My sense of it as a listener (and player of the 4-hand version) is that every compositional moment has been needlessly extended into a full musical sentence, purely for form’s sake, without consideration for the wants and needs of the material itself. The introductory section, for example, seems to me fully twice as long as it has any internal reason to be.

Of course, in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, this same kind of dutiful four-squaring of the musical sentences creates an impression of fantastical expansiveness, a timeless tapestry, not to be followed beat for beat but to be experienced as a landscape extending luxuriously in all directions. I suppose that goes for this piece too: when I let myself go and stop paying attention, I find a certain feeling of security in the unshakeably slow, tree-like quality of its thought processes. Ent music. Hmmmmm! Hmmmmm!

I tried several times to play the duet in a way that gave a genuine and unbroken excitement to the proceedings, especially to the development, but ultimately I don’t think that’s an option. The excitement is always necessarily grounded by being bound to an elaborate sense of propriety, and to enjoy the piece you need to meet it where it lives. Certainly all the tunes and sounds are quite appealing taken in 10-second chunks; it’s up to you to have a mindset that has appetite enough for a full 75 chunks, arranged rosette-style like a standard catering cheese plate.

Rimsky-Korsakov is generally better represented on recording than Glazunov, and certainly than Cui, so this piece has a slightly stronger showing than those above. Without much digging I count at least 10 recordings:

– Moscow Radio/Kovalev ~1954

– Lamoureux/Markevitch 1957

– Moscow Radio/M. Shostakovich 1960s?

– Bochum/Maga 1977

– USSR/Svetlanov 1985

– Berlin Radio/Jurowski 1996

– Moscow Symphony/Golovschin 1996

– Philharmonia/Butt 1998

– Malaysian/Bakels 2004

– Seattle/Schwarz 2010

Of what I heard, the Svetlanov is the most convinced and thus convincing. The recent Seattle recording definitely has the most color and kick, but sort of as an end unto itself; the question is whether that’s what you want.

See you next time.

2008:

2008: