Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Screenplay by Kouhan (Yasunori) Kawauchi

Criterion #39.

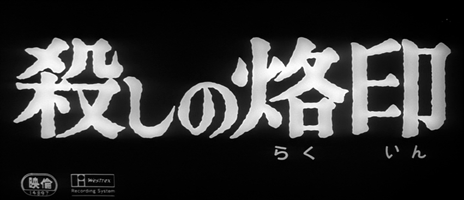

Tōkyō nagaremono. The English title is Tokyo Drifter.

東京 = Tokyo

流れ者 = nagaremono = stranger, wanderer, tramp

So “Tokyo Drifter” is literal enough, though in English it sounds like someone who drifts around Tokyo. In fact it refers to a man from Tokyo who drifts elsewhere. I’m not sure how to solve that one.

I’ll start with the essay – Criterion always commissions an essay, and the lively one from the 2011 release, by Howard Hampton, is pretentious and insightful and overwritten and satisfying. It’s how I would have them all be — a definite something rather than a nothing. In his flashy, Lester Bangs-y way, Hampton makes the case that this is a valuable and exciting movie, both thrillingly inside and thrillingly outside of the essence of 60s-ness. It’s a fun thing to claim and it’s a fun essay because the claim comes to life before your eyes.

But this is the thing about that sort of cultural writing: the magic act is all Hampton’s, and it depends on his materials seeming banal at first. Luckily for him the materials ARE banal. Which is why his claims aren’t really justified after all. The movie just is what it is: a genial, wacky, flamboyant piece of confusing, confused junk. The rest, the value and the excitement, is just stuff that we can say about it. And that’s fine! I want culture to operate that way. It just is, and then we go out for dessert and drinks, and burn it as fuel for our enthusiastic talk. The enthusiastic talk is the thing. “Can you believe??” Hampton’s essay was just that, for me, and so I was glad to have seen the movie, because then it was converted into fuel for that kind of play. But the notion that the movie, inert, is itself great, is silly. No it’s not.

Also, who cares if it is?

Taste is a racket. I’ve been saying this for a while and it’s useful to me to repeat it. Taste is not how we operate. Thumbs up vs. thumbs down has nothing to do with aesthetic experience. Experience has no thumbs. Experiences that we value do not generally conform to our own ideas of what constitutes “good,” or “worthy,” or “quality.” We just don’t usually feel comfortable admitting it.

In an enlightened enough frame of mind, we might value all experiences that come our way. At my best, I do, in fact, like all these movies. And on the flip side of that, in a bad mood, I don’t like any movies. I don’t want to watch a movie. I’m especially mad at stupid jump ropes! I need a nap.

“Good” and “bad” really have nothing to do with this kind of experience, and this is the only kind there really is. “Good” and “bad” are a racket.

Which is why it’s so needless to say that a movie is “good” when it’s not, it’s actually just fuel. Fuel is what counts!

Well, I just looked back over Hampton’s essay and I see that he never quite claims that it’s good. He just gets very enthused about what he’s saying. So I guess I approve after all. He showed me some tricks for how to burn the fuel. Prior to reading the essay it felt kind of soggy and unburnable to me, but it turned out there was a little heat in it.

Here’s what I got out of the movie: splashy visual flair of the slickest, most commercial sort the 60s had to offer, combined with a surreal disregard for many other things, including, especially, narrative cohesion. Hampton counters by saying that Suzuki’s “insubordination is perfectly coherent as such” but I’m not so sure I detect anything intentionally provocative. As I said last time, I feel pretty comfortable attributing the gonzo detachment to something behind and beyond the auteur. He’s not thumbing his nose at anything as far as I can tell; he’s just genuinely detached.

The movie is intent on playing it cool, and it certainly does that. It’s also not wearing any pants. But it doesn’t seem to know. You murmur uncertainly to the person next to you “do you see what I’m seeing?” It’s the dissonance between the absurdity and the conviction of coolness that draws you in.

Quentin Tarantino has undoubtedly spent some time here. I think I saw some scenes from Kill Bill in there.

To dorks like Quentin I think this kind of movie can be very exciting, because it shows that “cool” is just an act, and it’s an act that doesn’t lose its power even if you are pantsless. In fact it might have more power. The fight scenes here are ridiculous, with a lot of flopping around and falling down and backing toward each other and spinning around. But does that mean they’re not “cool”? How could they not be “cool”? Look at how completely stylish and confident everything about this movie is asserting itself to be! To Tarantino and possibly to Hampton, this kind of “cool” is if anything more cool than the better-coordinated American kind. What could be cooler than wearing your “cool” shades and smoking a “cool” cigarette with a “cool” attitude while sauntering “coolly” through the fake studio snow singing your very own “cool” theme song?

I guess nothing?

The Emperor might as well pop on some shades to go with those new clothes! Ohhhhh yeahhhh!

This movie would be great to play in your hip restaurant where for some reason you feel the need to show a goddamn movie on the wall while people are eating. It looks like great style, it looks like retro, and it’s not really worth watching attentively. And of course it just oozes cultural cred. Cred cred cred! So go ahead, asshole, loop it in your hip hip restaurant, see if I care. I guess I’ll have the farm-to-table portobello-wasabi sliders for $17.50. Fuck you.

Music by Hajime Kaburagi. As Suzuki says in one of the bonus interviews, this is “a pop song movie.” Tetsuya Watari, the lead, sings verses of the theme song at the opening, the close, in the middle, and in character. I was on the verge of simply biting the bullet and putting a song in my mix, but no. A song is a different animal, and doesn’t belong in my zoo. You can hear the entire song here (this is an album version that doesn’t appear in the movie; compare the main titles). For our compilation album I’m offering the actual first cue in the movie, a short instrumental version of the tune. Track 39.