directed by Robert Florey

written by Rod Serling

starring Everett Sloane and Vivi Janiss

Friday, January 29, 1960, 10 PM EST on CBS.

Oh my god! The stern anti-gambling moralist turns out to be a latent addict!

Of course, we all see it coming from a hundred miles away. Everyone has an intuitive grasp of the principle: the scold is always the one most in thrall to the thing he scolds. And that’s not just for TV shows; it’s how projection actually works. The difference between a negative fixation and a positive fixation is just words, and words can be ignored; the essential emotion being expressed is only fixation itself. The rule of thumb for the TV audience is that any character who says “If there’s one thing I know, Flora, it’s morality” is going to be exposed as a creep. Even if we can’t articulate it consciously, drama has taught us well that all disapproval is projection; all moralizing is hypocrisy. It’s just that being hypocrites ourselves, we’re generally not ready to admit that we know it.

Everett Sloane’s performance is quite good in this respect; he shows us physically that the severity of the scold is identical to the severity of the addict. The domineering husband whose wife doesn’t dare contradict him is transformed into: the domineering husband whose wife doesn’t dare contradict him.

All very straightforward stuff. So straightforward, in fact, that one may wonder why The Twilight Zone, which is to say Rod Serling, took up this subject at all. Reportedly the idea came to him while — get this! — playing the slots in Las Vegas. He observed his own sensation of compulsion, and thought “there’s an episode in that!” But the episode feels thin, or at least simplistic, because you don’t get the impression he was actually worried about being a gambling addict. It was just a hypothetical fear, with no real sting in it.

As with “Escape Clause,” our hapless protagonist is more of a cautionary nudnik than he is a real audience surrogate. That’s why the wife is there: to scoop up all of the leftover sympathy that we aren’t inclined to grant to the grimacing Mr. Gibbs. We might have once or twice entertained a worry about becoming an addict, on a whim, but really let’s be honest: that’s the kind of thing that happens to other people. And Franklin Gibbs is far, far older than 36.

Addiction is an interesting subject for the Twilight Zone treatment, but this isn’t a particularly insightful portrayal of addiction generally or gambling addiction specifically; Gibbs’s motivations are too vague. In the second half when he’s agitated because he’s got to win back his losses, that makes a certain sense: the shame of having begun to gamble is the same blot as the shame of being susceptible to temptation in the first place, and he’s willing to expend any amount of energy to wipe the blot away. But his actual seduction is left awfully sketchy. All we get is the creepy voice of the coins calling to him, after his hand is initially forced by a highly unlikely chain of events.

By keeping the thought process of the addict in shadow until he’s good and crazy, the episode lets the viewer off the hook. If he has no actual reason to become an addict other than a bunch of TV nonsense, then neither do we. Of course, we know that even a stock sourpuss character must have some inner wound. What is it that Mr. Gibbs wants, deep down, that makes him such a scold at the outset? That would be the real source of his being haunted, and Rod doesn’t dare touch it. We have to fill in the blanks ourselves. He’s lonely, probably? His parents were cruel to him? Oh who cares.

The hallucination that generates the climax is obviously contrived and silly, but for the blog’s sake I’ll still briefly address the principle of the thing: he projects this monster, and it’s with him. It knows him. As always, that means it’s a part of him that he hasn’t accepted. “A monster with a will all its own,” he calls it.

Franklin, like Rod, has a subconscious impulse to use the slot machine, and because it’s subconscious, it seems somehow external to him. He isn’t quite able to identify with it, because he fears his own subconscious — which is to say he fears other people’s responses to it. Why else would he lie to his wife, when he claims he’s only going to dump the coins back in the machine to rid himself of their sin? He makes excuses because he doesn’t trust her with the truth of what he feels, and the rationalization he invents to deceive her is soon adopted to deceive himself, too. The thing gargling his name at the end is just his own private inner experience, which he has tried to deny.

The obligatory Twilight Zone bet-hedging is to show us the machine lurking nearby even after there’s nobody left to perceive it; “maybe it was real after all!” But under the circumstances it just feels like going through the motions. Of course it wasn’t real! There hasn’t been any ambiguity about what we’ve been watching here. The wife couldn’t see it; it wasn’t there. The “literal” version, where an objective haunted slot machine objectively menaced this guy, doesn’t even hang together as pulp. (Why would it go hang out near his corpse?)

If you’re less jaded than I am and are able to grant the final shot its intrinsic meaning, it’s this: even the catastrophe that the anxious mind foresees for itself will not stop the subconscious, which lives ever on in its eerie otherness.

A more psychologically realistic ending would be for us to see Gibbs dead on the pavement, see the slot machine looming in the shadows… and then see Gibbs the next day, back at it again in the casino. The notion of being driven to some ultimate disaster is itself just part of his hallucinatory pathology. This is Gibbs’s bad dream, and every bad dreamer lives to bad dream again.

We have here a particularly absurd instance of the trope wherein suicidal madness can drive a man “out the window” at any moment. Mrs. Gibbs stands by in helpless horror because she understands all too well that walking very very slowly toward a window is an unstoppable act of absolute doom. Franklin has to back out of the window accidentally so that we don’t have to broach the subject of actual suicide, since under the flimsy circumstances it would seem distasteful. But we all know it’s code for suicide, or at least for self-induced psychic cataclysm. Rather than being what it is literally: a man getting a little upset in a hotel room.

Sadly, Everett Sloane really did commit suicide, six years later, possibly because he feared he was going blind. I didn’t know that before, and it’s going to make my viewings of Citizen Kane a little sadder in the future. We’re only 17 episodes in and we’ve already had Gig Young and Inger Stevens, too. The Twilight Zone isn’t shaping up to have a very good track record on this count.

In a sense, this is the most forthright Twilight Zone episode yet; it gets at the same old themes, but in what is essentially a realistic context. Barring the couple of hallucinations set to film, there’s nothing supernatural here. The issue is, as always, whether we can bear to live with our own fear, and what we do to rationalize it and push back against it when it overwhelms us. Here Rod gestures toward what are, indeed, familiar real-world answers to those questions. But he does it sloppily and with no great insight. Just enough to get the episode out the door.

Second one directed by Robert Florey, after the artsy “Perchance to Dream.” This assignment is pretty ordinary by comparison but he still brings some panache to it. Gibbs’s death sprawl is nicely laid out.

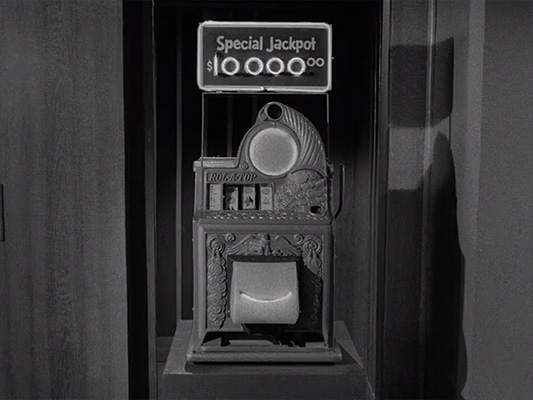

The monster in action. Bet you didn’t imagine it was yellow.

This episode uses library music, but in a limited and cohesive way. After a few loose establishing cues, it’s essentially just a score by Jerry Goldsmith borrowed whole from a Studio One in Hollywood episode of the previous year:

“The Fair-Haired Boy,” aired Sunday March 3, 1958 at 7:30 PM on CBS. Written by Herman Raucher. Starring:

Darren McGavin as Tom Kendall

Jackie Cooper as Dave Tuttle

Bonita Granville as Ann

Robert H. Harris as Pogani

Patricia Smith as Clare

Lyle Talbot as Trent

Ainslie Pryor as Dalsky

I find the action of “The Fair-Haired Boy” described variously as

“Partners in film company clash over ethics of public relations.”

“Although favorable results are soon realized with the art director and a young promising public relations man working as a team in a concerted effort to promote the company’s films, an animosity develops when the older man is suspected of claiming his partner’s ideas.”

“A murder takes place in the public relations department of a motion picture company.”

Which feels like a pretty good plot summary right there.

“The Fair-Haired Boy” doesn’t seem to be in the Paley Center collection, so for all I know it hasn’t survived, and nobody will ever again get to see Jackie Cooper kill Darren McGavin, or possibly the other way around. But we can still hear what it sounded like! Cool, is what it sounded like.

Plus Goldsmith’s music is supplemented by a perfectly matched piece of library music by René Garriguenc, called “Street Moods in Jazz.”

This atmosphere of forbidding angular hepness was a standard palette color in those days. “Crime jazz” had been on the rise for a while in TV and movies. That said, I suspect that the particular angles heard here are deliberately taking a page from West Side Story (1957).

I like the philosophical ambiguity in this kind of music: is it comic or serious? Is it threatening or charming? The less certain you are about how to name the mood it evokes, the richer the art, I think. These scores are richer than they might seem at first glance. Goldsmith and Garriguenc are responsible for imparting to this shallow episode a few faint suggestions of depth.