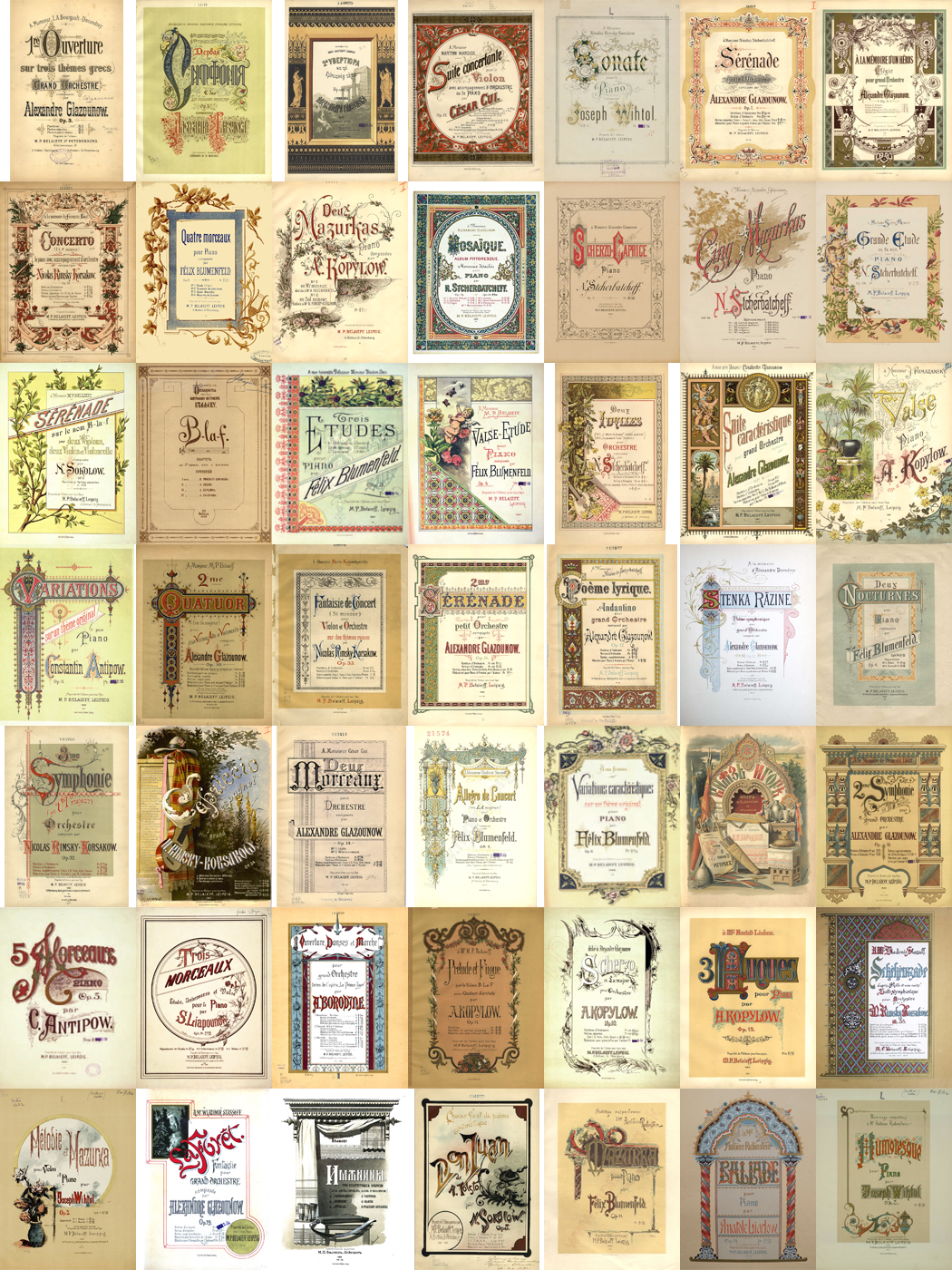

Here are the first 49 Belaieff-issued scores for which I’ve been able to obtain full-color images of the title pages. (Intermingled among these chronologically would be about 20 for which I have only black-and-white images, and 30 for which I haven’t found any images.) These are all from 1886–1890.

I was gathering these and then stacking them up as one of my OCD outlets and figured I’d post it.

Wanna see ’em closer up? Sorry, you can’t here. It’s just one big image. You can click to see it at its full scale, which is only a little bigger, and that’s it.

Wanna hear the pieces? Sorry, though I did consider mapping the image to link to Youtube audio for each piece. I guess I’m still considering it.

I think as many of 23 of these — i.e. about half — are not available on recording and never have been. There are 4 or 5 of them that it’s entirely possible have not been performed at all since the 19th century.

Whereas Capriccio Espagnol (3rd row from bottom, 2nd from left), Prince Igor (3rd row from bottom, 2nd from right), and above all Scheherazade (2nd row from bottom, far right) have gone on to perennial fame and fortune.

It’s 125 years later, and almost every day, Scheherazade is being performed for a paying audience somewhere in the world. That’s serious artistic success! (And note that the dances from Prince Igor are being played at one of those concerts, too. Capriccio espagnol isn’t being played today but it will be in two days. Also not too shabby.)

Meanwhile, say, Kopylov’s Two Mazurkas Op. 3 (2nd row down, 3rd from the left) have never been recorded — not even by Youtubers! — and I can find no indication that they have ever been performed publicly at all. They’re quite nice.

This feeds into a familiar thought for me and for my loyal readers: how much perfectly good culture is inevitably left by the side of the road as the caravan of history trudges wearily ever onward. (Something something Donner Party.) Actually I picture the Cretaceous trail of tears from Fantasia, where that hadrosaur slumps down to die in the dust. Belaieff didn’t publish Rite of Spring so this isn’t quite a perfect loop, but close.

But that old feeling of mine — pity the poor cobwebbed unknowns — has recently given way to a new one: the attic is just another room in the house. Sheet music isn’t a hadrosaur: when it’s left behind, it doesn’t actually die. Things that gather dust are only gathering dust, nothing worse. Shake off the dust and they’re ready to run the race again. Wins and losses aren’t permanent, just passing. Yeah, even the big ones.

Think of Pachelbel’s Canon, written for unknown occasional use (or possibly purely as an exercise) in Erfurt, Germany in the 1680s and promptly forgotten like everything else that happened in Erfurt, Germany in the 1680s. In 1919 the score was published in a German scholarly article on Pachelbel, the manuscript having been dug out of the cobwebs and looked at for the first time in 200 years, at a moment in history when nationalist antiquarianism was booming. Then 20 years later, Arthur Fiedler apparently came across it while trawling through academic sources to collect material for concerts of Baroque music — as well as for concerts of contemporary neoclassical music that could use a little taster of ye olde original. He recorded it in 1940, treating it as exactly what it looks like on the page: a quick crisp bit of old-fashionedness that doesn’t go anywhere. Then after another 28 years of obscurity, one Jean-François Paillard, who surely came to be aware of the piece from the Fiedler performance, made a very 60s-ified arrangement for his ensemble, which got included on a not-very-prominent Musical Heritage Society LP. Over the next couple years, this recording, which as you can hear is absolutely and perfectly suited to its 1968 moment, began to pick up some popularity within the classical market. Then in 1972 RCA Victor included the recording on a cross-marketed compilation LP (called, ahem, “Go For Baroque“) which sold very well… as a result of which, Marvin Hamlisch made the piece the centerpiece of his score for Ordinary People in 1980, thus cementing Pachelbel’s Canon as “a very famous piece of classical music that everyone knows.”

(Yes, it’s true, the immortal Pachelbel’s Canon apparently owes its fame to this album.)

(Is it good or bad that I got through a very long paragraph about Pachelbel’s Canon and its place in “the canon,” and didn’t even touch it? I’d like to see that as a sign of my sophistication and restraint.)

In brief: it took Pachelbel’s Canon 5 steps to go from the dust of centuries to permanent megafame: 1. Antiquarian “hem hem” glasses-pushing dissemination to university libraries; 2. One-off “just something off ye olde heap” obscurity-tourism, tossed at the general market without expectation of interest; 3. Shameless liberty-taking “oh man it speaks to us!” reimagining; 4. Deliberate “now this we can sell!” remarketing as already being famous; 5. Ahistorical “hey, let’s use that piece which is apparently very famous!” by unwitting people who happen to be at the center of the popular culture.

Probably we can imagine a version that skips step 2 and combines steps 3 and 4. And with all the resources of the internet, it’s possible that we can fold step 1 in with the others; nobody needs a little old professor to go through the dusty manuscripts at the library with a notebook and a fountain pen anymore, since the library has already scanned its entire holdings and put them online. So it seems to me that there are really three essential steps to catapulting forgotten works to fame: 1. Finding them and putting the genuine breath of life in them — easier said than done, but doable all the same; 2. Recasting them as already famous; 3. Having them get used in a prominent way by people who have fallen for phase 2.

I suppose the essence of viral internet memes is that phases 2 and 3 are a runaway chain reaction and really just need to be sparked.

So if I wanted to make one of Kopylov’s Mazurkas Op. 3 into an all-time classic, all I’d need to do, basically, is get it used in a TV commercial (or a viral video, same thing), which would immediately signify to everyone that it must always have been an all-time classic, which would thereby become retroactively true.

I don’t intend to try to do that. But it is heartening to look at the covers above and realize that they are not dead, just sleeping, and that any one of them could absolutely be roused if we put our minds to it.

Belaieff had very good taste, I think, and the lavishness of the title pages accords well with the lavishness of the music. Maybe I just have more of an appetite for this sort of thing than most.

Here’s a link to music: a collaborative quartet in honor of rich Mr. Belaieff (based on a motif that spells out his name, “B-La-F” (B = B-flat; La = A)), which is almost never played, but has at least been recorded. First movement is by Rimsky-Korsakov, second movement by Lyadov, third movement by Borodin, fourth movement by Glazunov. Third row down, second from the left.

(And here it is on Spotify. Depending on your situation, pick whichever source is less likely to insert a horrible ad between movements!)

Listen closely during this unremarkable but pleasant piece and see if you can hear the Flump! of a hadrosaur biting the dust. I used to think I could hear such things clearly — “nice try, boys” — but now I think that was always an illusion. There is no Flump! other than the one we fear for ourselves and project. The scent of failure is always imagined.

A better use of my imagination would be to aim it toward the completely reinvigorated, living 2015 embodiment of this piece. Where are the Ordinary People whose lives have to sound exactly like this? Maybe not so far away. I can close my eyes and see a movie to this music without having to force it in the least. And the longer I stick with it, the more recent and full-blooded the movie. If the performance is good enough, I can get up to the present moment. If it’s not, my present moment defines the terms of a better performance, and thus hands me the key.

That’s one way that art stimulates further creativity: in opening myself up to it, I either find that it knows me, or else I find that there are things it doesn’t know, and that in this process of hoping to make a connection, those very things that have failed to connect have ended up perfectly in hand and ready to put to paper.

Perhaps the post-Romantic obsession with artistic “originality” is a mutation of something more primal and more valuable: the urge to express artistically whatever one is carrying that has not yet had the experience of recognizing itself in existing art. In this way, the full emotional holdings of a community end up being shared and shareable. But to do this honestly, an artist has to always be open to the possibility that he/she might in fact be totally accounted for, that he/she might have no “unaddressed” stuff that wants to be expressed. I suspect that this is never actually the case for anyone, that everyone always has something unsaid left to say. But a lot of artists seem to be driven by anxiety that it might be the case, that if they just created from the gut, there might actually be nothing new there, so they don’t dare test those waters. Instead they calculate a surefire newness and give it a sharp defensive edge. Whereas actual artistic originality ought always to register like a sigh of familiarity: all that was lacking was the art itself.

Pencils down.

Yes.

Part A – delightful. Wonderful thoughts.

I’ve now played the Mazurkas. Lovely, playable, listenable. Grieg without the Norway. Borodin without the orient. Szymanowski without the extremes.

No hadrosaurs. Just napping.

Part B – wisdom.