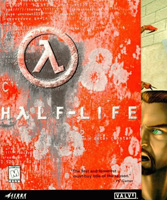

Half-Life

developed by Valve Software (Kirkland, WA)

first published November 19, 1998 by Sierra Studios for Windows 95/98/NT, $49.95 [original site]

~500 MB (~40 MB program, ~460 MB resources.)

Played to completion in 17.5 hours, between 12/18/14 and 12/29/14.

[Here’s video of a complete 6-hour playthrough in two parts. I played with the “HD” upgrade from 2001, this guy does not, so his characters and weapons look a little clunkier than what I saw, but otherwise the game is identical.]

I bought this exactly 4 years ago today, on 1/1/11. It was in a bundle with three other games for $3.74, so that’s $0.94 I paid for it. Approximately $0.05 per hour of play. Good deal.

I am here going slightly out of order of purchase: on 11/28/10 I bought “The Orange Box” on sale because I wanted to check out Portal (which I did immediately and thus have no need to revisit for my current purposes). The bundle included the much-praised Half-Life 2 and its two episodic follow-ups; I figured I’d eventually play those. Then on 1/1/11 Steam put “Half-Life 1 Anthology” on sale, so I bought it because of course I’d want to have the option of playing the equally much-praised “1” before “2.” And so that’s what I’ve done now, even though I bought them in reverse order. Even my OCD approves.

Nice thing about writing up games is that they take so long to play and are so readily paused that taking notes during the process is quite natural. Not like having to steal glances down at your notepad in the dark during a movie. So I have a bunch of notes here already, and I think once typed up, my entry can be done. I hope this can be my basic procedure with these game entries. i.e. LET’S KEEP THIS EASY, BROOM.

It’s bullet time.

• In the game, what are you doing is what’s happening to you, what’s happening to you is what you’re doing. Your actions both determine and are determined by the show you’re watching. They are it and it is them. Half-Life gives us free will as an on-rails experience, agency as a dark ride. Freedom to go anywhere, look at anything, shoot anybody, is subject to, and dependent on, continuous chaperoning by the universe. Every situation cues you to act freely in a predetermined way. Every ventilation shaft into which you must sneak contains your free choice to sneak into it. Active is passive; they are identical.

This is healthy. Videogame theorists and designers talk about the ideal of freedom, pure and unfettered freedom, but the experience of freedom in the real world is indistinguishable from the experience of fate. Games that attempt programmatic freedom run up against a philosophical point that is highly nuanced in the real world but like a brick wall in games: subjective freedom is not determined by objective freedom.

“Non-linearity” does not exist; life experience is linear. We tread a single path, in a single direction. The celebrated tram ride intro encapsulates this central grace of the game; this is why it is so celebrated. You are trapped in a tram and free; free to be trapped in a tram. Being able to move and look around during a staged dramatic sequence “in-engine” is more than just technical showmanship: it is the crux of the experience games have to offer. Just as with Pirates of the Carribean: you determine your own experience as long as it takes place within this boat, whose path is fixed. The special pleasure of Disneyland, as of Half-Life, arises from that equation of opposites, of agency with fate, of acting with being acted upon. This is the existential condition. Merrily merrily merrily merrily.

• First and foremost what is successful here is the writing. Not because the writing is remarkable as story or dialogue — it’s all quite gleefully, cheekily cliché — but because it is a singularly apt scenario for the underlying m.o. of all first-person shooters. This is good writing defined as good congruence with form, writing that lives in (lives the essence of) its medium. The scenario allows us to feel more wholly what we would already have been feeling below the surface.

• That is to say, this game is a thing of beauty because what it is IS what it is. Its realization of its own poetics, its Bachelardian underpinnings, is so sure and pure. The rest is window dressing. I was thoroughly entranced by it despite caring generally not at all for its constituent elements. Gross aliens, gore, weaponry, gunplay, military action. It didn’t matter that none of that is for me. I don’t like Pirates of the Caribbean because I like pirates. Rather the reverse, I’d say.

• Despite the considerable element of horror, revulsion, and tension, I found to my surprise that long sessions of play tended to clear rather than rattle my head. Fantasy, I think, is distinctly healthy for the mind. I used to think only gentle or mottled fantasy was wholesome, and extreme and pure fantasy was dangerous or embarrassing, but that was only a measure of my personal anxiety, which is to say my ideology of what kinds of repression were good and right and important.

Fantasy is healthy because it is inevitable. Repression doesn’t actually alienate us from our imagination, it just presses and molds it until its fantasies resemble reality as best we can manage it. But for all that they are still fantasies, governed by the same laws of irrationality. Occupation with overt fantasy, computer games and whatnot, is healthy because your mind is going to indulge in fantasies whether you like it or not, so better to have them freely and know them for what they are, rather than confuse them with real life, where they can actually do damage. Games and movies are useful to me because they absorb all my obsessive image-making power, vacuuming all those ectoplasmic images from out of the tangles of my life where they have lodged. At least temporarily.

“Escapism” as a pejorative is a destructive misnomer. I knew this as a child and now I know it again. The mind is always half-occupied with images that stand apart from the senses. Constantly forcing them into pseudo-compliance is far more destructive a form of denial than is clear-eyed interest in their natural dream content.

• First-person games are deeply dreamlike, which is to say psychologically apt. I have had many dreams in which I floatwalk through architecture that streams outward into my peripheral vision like toilet paper spinning wildly off the roll.

• Games in three-dimensional space are always principally the experience of that space, architectural experience. This experience can be very deep even when something shallow is happening in the game proper. All fantasy games have mysterious sanctums, rooms with candles, low lights, meditative, incensed spaces. This space is there to provide exactly the same fantastic welcome to the imagination that real people seek when they set up real candles. In fantasy, the values of imagined space and real space overlap, because all space is to some degree imagined. Game spaces do the very thing that real spaces do, serve the same human function.

• Of course, one must also have faith in the real world, faith that it can be just as gratifying, that candles and warmth also have a sensory reality. Otherwise one is a nerd, which is to say a fatalist about the possibility of ever living out the irrational in the world of the senses. There is such a thing as the lived irrational, not just the imagined irrational. It is a thing worth striving for.

• Half-Life is “The greatest FPS of all time” etc., and, for all I know, I concur, as above. But it is only what happens to exist, not an ideal realized. The dreams of spooling scenery are my good ones, but I also have dreams of constantly renewed skirmishes with hostility that comes skittering out of corners, of an existence that is an unending thread of necessary strategy: where to go next, how to defend next, what to fight next, what to avoid next. And dreams where the world mutates, where things are not attached right, where disgust creeps out through the walls and faces and bodies. The game is these dreams too.

• Close to the heart of the game is the alienation of all institutional lobbies, loading bays, steam tunnels, etc., etc. Why do movies always have shootouts in parking garages? This is not an arbitrary location! The production designer in my dreams agrees. Here is a hospital hallway that links to another hospital hallway that links to another: fight for your freedom. There’s a cultural/societal critique of the psychological role of institutions to be made here but I’m not tempted to go any further than this.

• At the end of all those laboratory hallways full of Giger creatures, in the inevitable inner sanctum, the final boss is a enormous mournful horror fetus floating serenely as a god in a horror womb in a dream dimension. This is apt to the logic of dream but I personally didn’t ask for it, just like I didn’t ask for all the preceding grossness. Becoming acclimated to nightmares-as-nightmares is impossible because they cease to be nightmares; then again neither is full unacclimated horror an option for entertainment. One must lose either the function or the ease, and thus the satisfaction in either case. The satisfaction on offer is the satisfaction of repression, which the game enacts ballistically. Hurl all the explosives you’ve got at the horror. The greater your facility at repression, the less frantic and more levelheaded your hurling, the greater your success on the game terms. This is not healthy. So there is a very rough price for me built into this particular fantasy.

However, for me, who is not personally at odds with any flesh or fetus, the real enemy is this price itself. So I win my personal game by playing exactly and only as it interests me, and not being bound by the implicit shaming of Easy vs. Hard mode (I played on Easy), flailing vs. skill (I quicksaved and reloaded every few seconds when there were enemies), fear vs. machismo (I was constantly scared by a game not generally considered to be in the horror genre).

• This game is so incredibly beloved that it was completely reconstructed and touched up by fans in a more sophisticated 3D engine, to meet lavish modern graphical standards. Black Mesa, i.e. Half-Life as rebuilt in 2012, would seem then just to be a technological fleshing out of the same game. But it’s not at all. The dream-meaning of all those spaces is bound up in their limitations, their being built with wit and showmanship out of a fixed vocabulary of primitive planes and nodes. The mind-clearing quality of the 1998 game is not available to me from the 2012 game. The new space is so much less forthright, claims to know so much more than it does.

An elaborate “skin” is an anxious thing, a bigger kind of lie than the old puppet show. When the buttons are just blurry allusions to buttons, I know very well what they are and why they don’t work. A richly detailed texture on the other hand is more of a conspiratorial deceit, more of a Truman Show. The new claustrophobia preens and leers needily, where the old one was composed, sphinxlike. A sphinx is scarier company than a con-man but less anxiety-inducing. I know well which I prefer, but I’m at odds with the culture.

• Here are two interesting articles and one video from behind the scenes. Humanizing computer games is as strange and fascinating as humanizing animated films. The experience is so completely a product of the imagination; even the technical side is its own kind of grand fantasy. The experience of this game has less than nothing to do with Kirkland, WA.

The opening credits are simply an alphabetical list of 30 names with no roles specified; the end credits are “Valve is”… and then the same list of 30 names. This is honest to a point: a computer game is a profoundly collaborative vision. But it’s also a sort of principled evasion. I poked around and determined that the principal real credits ought to be something like:

Produced by Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington

Designed by Ken Birdwell (animation system), Mark Laidlaw (writing), Jay Stelly (3D engine), John Guthrie (level design), Kelly Bailey (sound and music), Ted Backman (art). With about 15 others, but I suspect that this is the “original cabal” mentioned in Birdwell’s article linked above.