written and directed by Abbas Kiarostami

Criterion #45. Moving this along because it’s good to watch movies.

Iranian! Foreign language, foreign script! It’s been a while. Let’s dig into this.

First off, what is the name of this language? I thought it was correct to call it “Farsi,” but some investigation leads me to understand that for an English speaker like myself that would be needlessly affected, like calling German “Deutsch,” and that I should just call it “Persian,” which is all that “Farsi” means.

(And, for good measure: “Farsi” is actually only an Arabic modification of the original Persian word for Persian, “Parsi.” The political history is apparently such that nowadays Iranians generally call their language by its Arabic name, “Farsi,” with a kind of footnote “but the correct word is Parsi.” Anyway, the point is, that needn’t concern us in English.)

(P.S. And in case any of you dreadfully ignorant Americans need reminding, as I very very obviously do not and did not, Arabic (spoken in Iraq and westward) and Persian (spoken in Iran and eastward), are completely unrelated language groups, but after the Arab conquest of Persia in the 600s, Persian speakers adopted Arabic script, and thus modern Persian is written using a close variant of the Arabic alphabet. I pity your Western ignorance for needing to be spoonfed this very basic information about the world around you. For shame. I for one clearly had this all well, well in hand prior to googling it and reading Wikipedia.)

(P.P.S. But seriously: I think I would have basically gotten it right if asked nicely. But now that I’ve looked it up we’ll never know.)

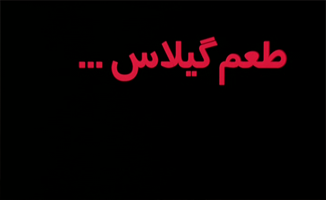

So here is our title: طعم گيلاس …. If you copy and paste those letters and fiddle around with them you’ll see what fancy stuff your computer is ready to do with Arabic/Persian script. The letters automatically jump into right-to-left order when you link them up, and switch shapes on context (with different forms depending on whether a letter appears at the beginning, middle, end, or isolated). They feel a little sticky and alive and unpredictable. We Latin alphabet users don’t get to see that kind of magic in our ordinary typing. Savor it! And apparently the computer also knows something (though not everything) about what order to put the words in, because once it picked up on the Persian I had a heck of a time getting “(1997)” to show up to the RIGHT of the title. The cursor jumps around in weird ways when it thinks you want to go right-to-left for a while. Even just selecting the text is weird. Try it, it’s fun.

Obviously this font size is inappropriately small for Persian. Luckily, none of is are actually reading what it says.

Okay, okay, let’s get to it.

طعم = ta'm (the ' is a glottal stop, the first sound in “uh-oh”) = Taste

گيلاس = gīlās (the macrons just indicate long vowels) = Cherry

The romanization on Wikipedia is Ta'm-e gīlās…. The romanization on IMDB, which seems to have been distributed at the time of the film’s release, is Tam e guilass. (I speculate that the “gui” may be an artifact of its appearance at Cannes, where French speakers would have needed the “u” to make clear that this was a hard rather than a soft “g.” Yes?) As far as I can tell the “e” particle is just contextually implied.

So word for word this would be “Taste of Cherry” and this is indeed the English-distribution name of the movie. But as far as I can tell from google translate, written Persian doesn’t generally use articles or distinguish plurals, so “The Taste of Cherries” might be equally valid. It’s certainly more the implied title of the movie. (Subtitle for the relevant line of dialogue is actually “the taste of the cherries” — though I’m not sure the spoken phrase is identical to the title; I can pick out “gīlās” but not “ta'm”.) “Taste of Cherry” seems to me a bit needlessly gnomic and foreign-film-ish.

And this all ignores the ellipsis, which seems a rather significant feature of the title. “Taste of Cherry…” doesn’t really make any sense, since the phrase is semantically too abstract to sustain any sense of time. But “The Taste of Cherries…” is sensible enough. If a little cheesy. I don’t know what to google to find out whether ellipses indicating lapses into reverie are equally cheesy in all languages. But cheese isn’t my problem, it’s Kiarostami’s. I put it to you that the name of this movie is: The Taste of Cherries…

Now that’s overwith, we can finally get to the part where I say something about the part of the movie that isn’t the title.

First I will let Mr. Kiarostami say a few words on his tastes, taken from the disc’s sole bonus feature, an interview:

I don’t like to engage in telling stories. I don’t like to arouse the viewer emotionally or give him advice. I don’t like to belittle him or burden him with a sense of guilt. Those are the things I don’t like in the movies. I think a good film is one that has a lasting power. And you start to reconstruct it right after you leave the theater. There are a lot of films that seem to be boring, but they are decent films. On the other hand, there are films that nail you to your seat and overwhelm you to the point that you forget everything, but you feel cheated later. These are the films that take you hostage. I absolutely don’t like the films in which the filmmakers take their viewers hostage and provoke them. I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theater. I think those films that are kind enough to allow you a nice nap and not leave you disturbed when you leave the theater… Some films have made me doze off in the theater. But the same films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks. Those are the kind of films I like.

I include this because it is a sort of manifesto for a certain kind of moviemaking, stated bluntly, and in a way, everything I have to say in response to this movie can be said in response to this, its rationale. (This allows the reader who has not seen the movie to engage more directly. You see? Very considerate of me.)

Though I guess such readers will need me to say outright: I thought Taste of Cherry (yeah, whatever) was indeed the sort of film he likes, the sort of film he wanted it to be. It is unapologetically slow and quiet and subdued. It introduces a situation revolving around isolation and the contemplation of suicide, and then lets the mood and meaning of that situation seep into the lyrical but simple imagery of a man driving around in a mostly barren Iranian landscape of grassless dirt. One is lulled, if not to sleep, at least to a peaceably bored calm. The muted grinding of tires on gravelly roads is as soothing and meaningless in a movie as in real life. It only took a few minutes for me to understand why it was going to be okay for a full-length movie just to consist of slowly driving around: for the same reasons that people enjoy actually slowly driving around.

And what are those reasons? I can’t help but return to the subject that has preoccupied me (to say the least) for the past year or two: the condition of being a brain, and the care and feeding of brains. (Or “minds,” if you prefer.) What kinds of things do minds like? One point of view would be that there are two distinct sorts of things, and Kiarostami lays out them out side by side in his quote above: one is to be stimulated, and one is to be unstimulated.

Another point of view takes a step back and says there is really only one thing that brains like: to be stimulated and unstimulated in equal measure. Balance. One can imagine some ideal median degree of stimulation, but in practice this is an impossibility and what one really aspires to is something like a well-modulated steady wave of stimulation alternating with unstimulation. My sense, in fact, is that the alternation is part of what brains like, just the way people enjoy swinging on a swingset more than they enjoy sitting at rest on a stationary swing.

When I was younger, my patience for “art movies” like this one was quite a bit shorter than it is now. I definitely had a good open mind about such things: I wasn’t particularly prejudiced, culturally, and I was certainly very much game to be transported into a meditative state if that was what a movie had to offer. But whenever it became apparent to me that a movie (or any sort of art) wasn’t going to prescribe anything in particular for me to do with my mind while watching — that I was under only very lax supervision by some kind of Montessori hippie movie — I would spontaneously feel that I had better things to do and think about. Encouraged to let my mind wander as I liked, I would accordingly do exactly that, and it would eagerly wander away from this lazy movie, toward things I cared about.

As I got older and more defensive, more intrinsically interested in picking apart the mysterious fallacies and hypocrisies of human society, the peculiarity of such movies would hold my attention even when the movie didn’t, and my wandering attention would drift outward, to think about the movie as an artifact, about the people who made it and were showing it, and about the dubious “artsy” attitude that had thought there was some virtue in confusing watching-a-movie with not-necessarily-watching-a-movie. I grew cynical: such films didn’t really want me to freely have my own thoughts; they wanted me to have the thoughts they intended, but they also wanted to congratulate themselves, and wanted me to congratulate myself, for my arriving at those thoughts freely, without coercion. Or rather, pretending in bad faith to arrive at them freely, while actually secretly following the filmmakers’ breadcrumb trails of high-intellectual clues, which generally led nowhere all that great: just to a big crumbling piece of stale bread. High art wanted to have its cake and eat it too: no prescribed experiences, but exceptional experiences nonetheless.

It seemed to me impossible for such art to justify its existence in preference to such superior unprescribed experiences as, say, looking at a tree, or looking at a kaleidoscope. Or looking at nothing and letting the mind wander. I can have all the rewarding thoughts I want with my eyes closed. So who needs authors if they’re not going to author an experience? Only god can make a tree so give me a freaking break, am I right? The Empire Strikes Back made more sense to me than the likes of Le grande illusion not because my mind was so dulled and stunted that I could only find enjoyment being strapped into a rollercoaster, but rather because my imagination was so free and strong that I could only recognize a rollercoaster as genuinely having determined or even demarcated my experience in any way worth naming.

And I still stand by the legitimacy of this point of view. When Kiarostami speaks derisively of movies that “take you hostage,” I find that unsympathetic and wrong. Being manipulated is one of the great pleasures in life; being stimulated is one of the two great pleasures of the mind.

But nowadays I also understand the sense behind movies that cater to the other great pleasure. I finally see the real purpose of all that Montessori art. They were not for people with unfettered imaginations. They are for people whose minds are already full, who have made a habit of overthinking, and for whom the “unstimulation” offered by a tree or a kaleidoscope is something — crazy as it sounds to a child — that has come to seem rare and precious to them. Since they can’t always see the world through their thoughts anymore, they desperately want to be offered the world directly, by other people, by artists. The target audience for a Taste of Cherry is people who go “ah!” when there is quiet because they have come to expect no quiet.

This is generally called “being an adult” but I resent that. People can use their minds however they choose at any age and the number of available trees to look at is the same for adults as for children.

I understand a “down-time” movie now much as I understand a “guided meditation,” which also would have baffled me as a child, as it should. There is something quite sad about having gotten to the point where one feels comfortable being oneself only when being guided to it by someone else. And this is what art films are. But the state of mind in which one is desperate to be granted the right to inattention by the thing you are compulsively paying attention to is very real. It is for this state of mind that such movies are designed to work, and having unfortunately attained that state of mind, I can attest that they do work, and are moving as such. At least this one was.

It also begins to make sense to me that such movies are often associated not just with the ambitions of high intellectuals but also with the political cinema of poor or oppressed populations. The mind that is constantly enmeshed in a struggle against overwhelming problems is a mind that will by force of habit not be able to help but fill in blanks, and thus will seek an art of as many blanks as possible, in the hope that at least some will manage to remain blessedly blank even after the mind gets a stab at it. I have come by my anxieties wholly apolitically, of course, but the principle is the same.

It’s tempting to say that I hope for the day when I will find these movies pointless again, when I’m no longer anxious enough to need to be fed boredom. But actually, in having come this far down the path of overstimulation and gotten to personally comprehend the value of naptime cinema, see what its deal is, I have divested myself of my old cynicism that art-house calm is affectation, or that what’s being asked of me is to fake freedom but actually follow the leader. And the cynicism was the only reason I didn’t like such movies. Without that cynicism they may well be no better than looking at a tree, but also no worse. And I like letting my mind wander. I am actually perfectly content to let my own imagination be the form and substance of my experience, and why shouldn’t that be part of the public culture of going to the movies? Or any other part of society?

In retrospect I do wonder now if my skepticism about Montessori attitudes was exactly the damage done to me by public school, was exactly the stunted Americanized attitude that it’s said to be. Undoing that sort of damage means realizing that I like being given free rein, in all things, including movies. Why not?

They are there for me to watch. When you put this disc in your DVD player you can see a golden-brown world of dirt. That sounds, like so many things, good. And even better: it is a world that wants to be seen, that was made to be seen. I don’t expect ever again to doubt the value of that. There will always be occasion for the gentle downswing of my mind’s stimulation cycle.

[In sum: there is nothing wrong with manipulative, hostage-taking, overstimulating movies. But there is something wrong with disdain for the opposite. The big cultural/socio-psychological problem is partisanship for one or the other. People like Kiarostami (as self-represented above) just contribute to polarization when we really need integration.]

Interestingly enough, when this movie first came out, Roger Ebert caused a stir by writing a one-star review, saying that he thought more or less what I gave as my childhood attitude, above. That the movie was an emperor with no clothes, pretending to profundity by being ostentatiously boring and empty and wasting the audience’s time. All points of view are subjective and thus legitimate and I’m sure in that moment it seemed that way to him. But I can’t imagine the post-surgery meaning-of-life waxing-blogosophical good-ol’ Unca’ Ebert of 10 years later being at all impatient or cynical about this film. He was all about letting his mind wander; he was all about the taste of cherries. Wake up and smell the taste of cherries. Life is just a bowl of the taste of cherries.

I enjoyed it, and I benefited from the time it gave me. I thought about what it was about, and about myself, and about the world. I was moved when it seemed to be moving more or less in synchrony with these thoughts, which was most of the time. It seemed in fact to be about… the issues above, the privations of thought and the relief of the unthought of the sensory world. (It is of course characteristic of the unstimulating art movie experience that whatever you are inclined to think about seems to be wahat it really is about. But in this case, y’know, I think it really was.) On the movie’s small, quiet scale, I felt a slow trickle of feelings of tension and apprehension, and nuances of real discomfort, comfort, hope, and hopelessness. Toward the end I realized that the steady trickle had accumulated a small but real quantity of feeling, and that the filmmaker might be playing a long game where he would end by suddenly flushing it, which might well make me well up or feel horror or joy or something. And after spending an hour-and-a-half in slow time, I was prepared for him to give me one meticulously prepared shove into bigger feelings.

Well, that’s not what he did. This movie ends with a high-concept coda, in which the possibility of cashing in the accumulated emotion is pointedly set aside, apparently on principle (again, see filmmaker statement above). Instead he shows us [spoiler redaction, if this is a spoiler, though maybe it shouldn’t be]. A lot of the discussion of this movie focuses on coming to terms with the anticlimactic jolt this gives the audience, and its possible significance. Certainly in the first few minutes after viewing that’s what was on my mind. But then I came to terms with it, and the terms are: it’s not really that important to the movie. If you’re suddenly startled by someone being near you because you were wrapped up in a book, it might take a while for your heart rate to come down, but hopefully it doesn’t take nearly as long for you to realize that what happened to you wasn’t actually very interesting. The ending isn’t really all that interesting.

There was no music at all (in one scene there was some very faint and scratchy music on a radio but completely under dialogue) and among my peaceful thought processes was “I wonder what I will do about the music selection; maybe I’ll just take some of the ambient driving sounds that make up so much of the soundtrack.” But then a-ha, at the very very end some music starts up and runs through the credits. It’s immediately recognizable as Louis Armstrong playing “St. James Infirmary Blues” (used without credit and, I wouldn’t be surprised, without paying for it), but something is odd. It seems to be two different performances being played simultaneously, or different parts of the same performance. The effect is a little eerie but, while watching the movie, pretty subtle. I’d say it was done to foil the copyright robots on Youtube except this was 10 years before anyone even considered being a tube.

At least some of it, I’ve determined, is from his 1959 studio recording on “Satchmo Plays King Oliver” (though from an “alternate take,” not released until 1979?), but it has been chopped up and shuffled around to skip the vocal. (Maybe the double-exposure effect is just done to help disguise all the splices?) And that 1959 recording ends on a high note, whereas this ends on a low note, so I can’t for the life of me figure out where the latter part of this track comes from. Nobody online has done this detective work and my patience ran out after a while.

Anyway, here you go, track 45. It starts under the last line of dialogue but it seemed better to get the beginning of the music than avoid the few seconds of talking. I faded in as a compromise.

Sometimes the faster I write the longer they get.