directed by Terry Gilliam

written by Michael Palin and Terry Gilliam

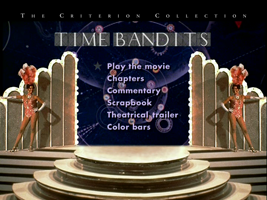

Criterion #37.

In E.T. (1982):

Elliott: You can’t tell. Not even Mom.

Gertie: Why not?

Elliott: Because, uh… grown-ups can’t see him. Only little kids can see him.

Gertie: Give me a break!

This would seem to be an early example of kid culture having knowingness and eating it too. But it — and E.T. as a whole — plays well because it feels what it preaches. E.T. is a classic because it does not condescend to the idea that the emotional life of a child is glorious; it simply plays it straight, makes a movie of it.

Elliott is trying on adult shoes here. He is constantly fed this kind of crap, and now with that dangerous principle of emotional logic (“do unto others as was done unto you” – this principle needs a name) is playing the adult role as he understands it. Garbage in, garbage out. But he’s still young enough that when she rolls her eyes he instinctively bows before the force of truth and changes tack. A real adult would angrily redouble the bullshit in the face of such purity. Adults feel subconscious shame that they are spewing garbage, which is why it’s so easy for kids to see through them.

The scene is rich because the very movie to which it belongs is feeding us something superficially quite similar (although it is essential to the emotional meaning of E.T. that adults can see and feel him, that he is simply there and real), but unlike Elliott’s lie, the movie earns our trust and belief, in no small part through exactly what this scene exhibits: unflinching ease with the fact that part of being a kid is knowing shit from Shinola. Gertie’s dismissal is not a cynical counterbalance to her innocence; it is an essential piece of it.

Yes, the emotional life of a child is glorious, and an important part of that emotional life is the sniffing out of pandering bullshit. In fact, I’m finding that open disdain for the absurdly obvious gap between feeling and pseudo-feeling is proving to be my surest Proustian hook back into that life. Right, that’s what childhood felt like! “Stop telling me lies about magic, because you’re distracting me from magic.”

And yet, like I said, here’s Elliott trying out bullshit, seeing what it’s worth. Another reason E.T. doesn’t feel like pandering is because it does not exempt the children from simultaneously being adults-in-training, with all the bluster and pettiness that entails. Even E.T. himself, the “thou” to Elliott’s “I,” is not exempt from playing at ugly adulthood, drinking all the beer he finds in the fridge and then watching John Wayne on TV, the patron saint of self-satisfied pig-in-a-poke grown-up-ness.

I bring this all up because E.T. seems to me the ideal archetype of the “kids know what adults don’t” movie. It has its head on straight, including about this potentially touchy issue, the fact that being a movie makes it a very adult artifact. It seems to me that the exchange above is not a lampshade; it’s artistic self-acceptance, the very opposite of self-consciousness. The E.T. screenplay alludes to Peter Pan but it is not Peter Pan; it does not dangle “never growing up” over our heads as a magic possibility to make us cry wussy grown-up tears of shame. Or rather it does, briefly, but in the end it does not endorse them: the part of E.T. that makes me cry is when Michael, feeling old, curls up to sleep in the toy closet as E.T. dies; he can’t figure out what to do other than make a futile, merely ceremonial gesture of love for his lost childhood. My tears, I am realizing now, were never for childhood/E.T./innocence — which are indeed resurrectable as per the movie — but for the feeling of impotence that has reduced Michael to nostalgia. Nostalgia exactly because he’s distorting the thing he’s nostalgic for; it is indeed something “only little kids can see.” What is there to do but cry in the closet? I know those feelings well, and feel for him, and I don’t resent the movie for making me tear up in this way, but the important thing is to recognize that to this the movie has already wisely said: Gimme a break!

Anyway, this is all my roundabout way of saying that the “kids know what adults don’t” trope is really about emotional honesty. The magic things that only kids encounter — be they aliens or talking animals or magic portals or mythical whatevers — represent things that are simply true and real and obvious. Such as feelings. Or details. Or the intensity of sensory impressions. Or the strange and mysterious mental phenomena that tangle the three together.

And, as in E.T., part of getting that childlike emotional honesty right is remembering what it’s like to know — immediately, tactlessly, comfortably — when adults get it wrong.

Time Bandits is Terry Gilliam “doing” childhood. Like Spielberg he is doing it uncynically (or at least like Spielberg prior to his 1989 divorce, which, quickie psychoanalysis, in recapitulating his parents’ divorce tarnished his sense of immunity to adult bullshit and opened the door to making the anti-E.T.: the rampantly self-pitying, calculated, impotent Hook. I suspect/project that the reason Hook sucked was because he was secretly distracted by self-fulfilling anxiety that he had suddenly grown up after all, and was faking his “eternal child” thing.)

Sorry, so, Time Bandits is adult Terry Gilliam’s take on what adults can’t see. They can’t see imagination, silliness, fantasy, play, cleverness, faraway lands, the joy of a big anarchic mess o’ stuff. Of everything. All the stuff on the floor in a boy’s bedroom, or in an illustration in a history book, or in a weird dream; why don’t parents care more about all that great stuff? This is to him the essential childhood question. Looking at his work it isn’t hard for me to imagine him as a child for whom this would be the essential question. And that truth comes through; this is very clearly a movie made from within this attitude and in the belief that the attitude is a pure and important one and in itself justification enough for a movie.

And yet my Gertie-meter went off a bit. But in the opposite direction from usual. Rather than playing the sad-wise adult who knows that childhood is a fairy’s tear that falls but once, boo-hoo, he plays the stubborn-angry teenager who knows all too well that adulthood is a big smarmy scam. In the middle of a celebration of the power of the unbridled imagination, satirical cynicism strikes a wrong note, one that a child knows only belongs to the curdled posturing of grown-ups. Imagination is great, so why are we hating on modern society? Or grown-ups? Who would waste their time hating grown-ups? Only a kind of grown-up.

At the end, rather shockingly, he has the protagonist boy’s house burn down and his inattentive, hopelessly materialistic parents actually explode when they encounter the dangerous vitality of the fantasy evil with which their son has been contending. The final beat is presented as a slyly melancholy one; uh-oh, now he’s got no home or family and has to contend with… life! Is that going to be the good kind of life, with dwarfs and derring-do and complete freedom of action? Or the bad kind where you watch idiocy on TV and cover all your furniture in plastic? It’s up to him!

Well, that’s all well and good for middle-aged Terry Gilliam, but for actual kids there is something off-key about the way that ending disturbs — specifically that it clearly knows it’s doing something wrong, something kids don’t deserve to have to see. Why? “Unto others as was done to you.” Yes, it’s human, but it’s not a good policy for art-making.

So that’s the problem; it’s a movie that doesn’t waste its time trying to “work” in any humdrum traditional way — it puts all its money on innocence and magic — and yet it hasn’t entirely washed out its soul. That said, there’s lots of fun stuff here. Gilliam stands almost alone in his willingness to bring a spirit of play to every aspect of movie-making, rather than reserving a few dimensions for ego (or anxious timidity). Imagery that seems to plug directly into the giddy freedom of making imagery is oddly rare in cinema. Even when his movies don’t work, I can’t help but feel that I am in the company of a vital creative attitude, and thus that I am somewhere worth being. Unlike most movies, his movies feel healthy, like you can breathe the air, feel aware of your body while you watch them. On the other hand there is that nugget of spite in all of them. Why didn’t they love me more, dammit?

A lot of it is on the table in this interview. Gilliam actually mentions E.T. He says he thinks the movie would have been better if the creature had been uglier, with narrow eyes, so that the kid had to learn to love it. “It should have been difficult to love E.T.” This is Gilliam’s prescription for everyone else, for all the Americans who lapped up the movie without reforming their hateful ways. He understood the movie fine, because he already loves his inner child — but to everyone else he’s apparently ugly. They could use a primer on loving him!

Time Bandits has a loving father figure in it — Sean Connery as Agamemnon! — but he is betrayed and left behind. At the end he reappears for a split second as a winking fireman, driving away from the rubble of the boy’s former home. Is all love and comfort a tease? Terry hasn’t worked that out yet, quite.

This is a pretty well stuffed homemade toy chest of a movie, but a scary one, and a lonely one. The former issue would have been a bigger deal for me as a child, but that’s because I was a well-adjusted child and could afford to be terrorized by ghouls. The latter is a more significant artistic failing.

I’m very glad to have seen it. There are several really wonderful moments in this movie, things completely pure of any resentment. When, in the middle of a desert, an invisible wall shatters and reveals a vast looming fantasy castle of evil, it is absolutely thrilling. There is, haphazardly, real imaginative joy on the screen. And then there’s other stuff too.

Score is by Mike Moran, the fantasy synths you might imagine for 1981. Main Title.

I watched this on Netflix, where it can be streamed in high quality. But of course the compulsion here is to watch the CRITERION version, and that meant waiting nearly a month for the single copy in the New York Public Library system to pass through three holds and finally reach me. By which point I had already written all of the above. And even this paragraph, because I got that impatient. So, do I have anything extra to say having heard the commentary track? (and the behind-the-scenes galleries??) :

Eh. It’s a pleasant, personable commentary, with an emphasis on how things were achieved on the cheap. But after all this wait it was bound to be underwhelming. I really just wanted permission to post. Permission granted.

Here’s what I do want to add, now that I’ve been forced to wait, and thus given the opportunity to read all the above through new eyes: art is a very personal business, for the makers and the viewers alike. I don’t think any of us have a choice about that. So let’s please try not to pretend that there’s any way of doing this that isn’t very personal. I don’t know if what I said was right; all I can do is swear that I meant it.

My concerns now (i.e. loneliness being a greater problem than scariness) are just my concerns now. My goal is to be a person to whom any attitude seems artistically viable because I am already fine, because I have other ways of getting what I really need from my fellow man. I want to get back in the mood for games.