’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

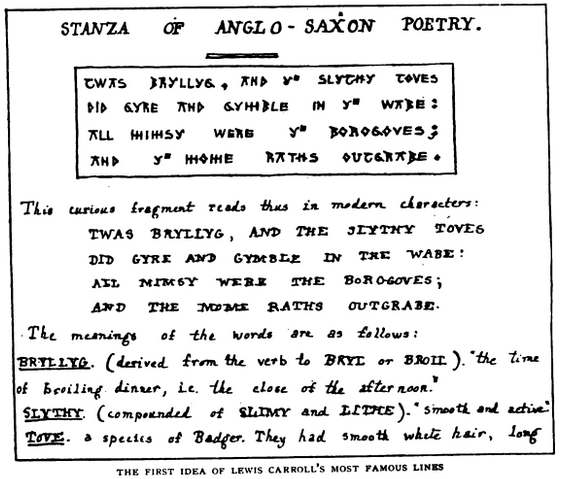

The first stanza of Jabberwocky stands apart from the rest of the poem. It’s distinctly more opaque — it contains eleven invented words where the other stanzas have no more than four or five — and it has a separate history from the rest: Lewis Carroll originally wrote it as a standalone bit of whimsy, years before the Alice books, and “published” it in a homemade magazine that he produced for the amusement of his family. In this form it was already accompanied by absurdist glosses of the made-up words, which he elaborated and updated in Through the Looking-Glass years later.

It seems like whenever anyone raises the question of what these words actually mean, no matter how academic and serious-minded the context, Carroll’s tongue-in-cheek glosses — which are very clearly intended to be ridiculous — are generally offered deadpan (in the manner of nerds who take pleasure in repeating “funny” things they’ve memorized because they think it constitutes participation in the comedy). I’ve never seen a source that attempts to correctly parse the stanza. But I have long believed this to be possible, and after many years I find myself in the mood to put this here for posterity.

My thesis, of which I have become fairly convinced, is that the stanza is meant to be recognizable as conventional scene-painting of efflorescent springtime, mentioning successively fauna, flora, and birdsong. The conceit is that this is archaic Middle English, so a modernized respelling should be possible. Consider, say:

‘Twas Maytide, and the lissome roe

Did graze and gambol in the mead

All rosy were the hellebore

And the song thrush gave call.

This at least is what I find jotted in my iPhone notes from a few months ago. I’ve toyed at making a translation-in-kind like this for a long time, and this was my most recent pass at it; it’ll do for posterity purposes.

“Maytide” is the worst of it: “brillig” actually probably means “sunny” (re: “bright” and “brilliant”), but there’s no suitably antique two-syllable word. (“Blazy” could work but only very poorly.)

The relation of “gimble” to “gambol” is the linchpin; it is particularly and specifically convincing to me. From this, the rest falls into place. “Wabe” must be a field and “tove” must be some sort of creature capable of gamboling; if we take “slithy” to be, indeed, related to “lithe” (and perhaps “slender”) then deer seems likeliest. “Gyre” as paired counterpart to “gimble” must be either synonym (i.e. “prance and gambol”) or contrast, as I have it here.

“Outgrabe” is clearly the past participle of a verb indicating vocalization; in this context it must be birdcall. “Song thrush” above is just a rough approximation (though “thrush” does satisfactorily preserve most of the phonemes of “raths”). It is unclear to me whether “mome” is part of a two-word name (as in “the song thrush”) or is a separable adjective (i.e. “the red robin.”)

By process of elimination within the overall cliché, the remaining clause, “all mimsy were the borogoves,” must refer to the plant kingdom, and this fits nicely, since the adverbial use of “all” in this construction is generally associated with expressions of sweet abundance or flowering. “Hellebore” is fun because it preserves “bor,” but I doubt it’s specifically what’s intended. “Groves” might also be relevant.

The possibility that “mimsy” and “mome” are deliberately linked in make-believe etymology, and perhaps refer to pink and red respectively, does appeal to me.

I do wonder why “toves” and “raths” are given as plural; it seems to me that the characteristically archaic construction for this sort of scene-setting would speak of, say, “the stag” and “the hare” etc., in the singular. It may just be that Carroll decided the singular was too confusing when the words are all made-up, and that the resulting ambiguity was unhelpful to the effect. (Then again maybe it didn’t occur to him at all. Or maybe I’m wrong about all of it.)

I did some very light searching to see if I could perhaps find a specific model for any of these phrases, or even for the stanza as a whole. I didn’t find any smoking guns, but I was rather struck by the following. Though I have no idea whether this text was known to Carroll — nor do I have the patience to do the real research necessary to investigate such matters — it at least feels apropos. Try reading this and then immediately reading Carroll’s stanza. The sense of parodic reference is strong and, I think, clarifying.

This comes from a fairly well known work that might well have held interest for Carroll, The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian by Robert Henryson (fl. c. 1460-1500). The language is Middle Scots.

In middis of June, that joly sweit seasoun,

Quhen that fair Phebus with his bemis bricht

Had dryit up the dew fra daill and doun,

And all the land maid with his bemis licht,

In ane mornyng betuix mid day and nicht

I rais and put all sleuth and sleip asyde,

And to ane wod I went allone but gyde.Sweit wes the smell off flouris quhyte and reid,

The noyes off birdis richt delitious,

The bewis braid blomit abone my heid,

The ground growand with gers gratious;

Off all plesance that place wes plenteous,

With sweit odouris and birdis harmony;

The morning myld, my mirth wes mair for thy.The rosis reid arrayit rone and ryce,

The prymeros and the purpour viola;

To heir it wes ane poynt off paradice,

Sic mirth the mavis and the merle couth ma;

The blossummis blythe brak up on bank and bra;

The smell off herbis and the fowlis cry,

Contending quha suld have the victory.

The fairly shallow reasons why these particular stanzas happened to catch my eye: the mention of “bemis bricht” reminds me of “brillig,” and “gyde” superficially resembles “gyre.” The phrase that first snagged my attention was “Sic mirth the mavis and the merle couth ma,” which has a very similar cadence to “all mimsy were the borogoves and the mome raths outgrabe.” (Though if correctly parsed, the syntax is actually entirely different; the Henryson is equivalent to “Such mirth the thrush and the blackbird could make.”)

So, yes, there’s really very little in common here. All the same, I’m pasting it into this scrapbook of my thought process.

In its original homegrown publication, Carroll’s mock exegesis ends by calling the stanza “an obscure, but yet deeply-affecting, relic of ancient Poetry.” This phrase, “relic of ancient poetry,” would seem to refer to a well-known and influential collection, “Reliques of Ancient Poetry” by Thomas Percy, which is a compendium of exactly the sort of stuff Carroll is parodying, and probably is in fact the book Alice finds in the looking-glass house, in which she reads “Jabberwocky.”

I browsed through the online edition looking for a model for the “’twas brillig” stanza, but didn’t find anything obvious. (There’s some Henryson in the collection, but not the passage above.)

However I did find some stuff that seems likely to have influenced the monster-hunting narrative that forms the bulk of Jabberwocky:

Than was he glad without fayle,

And rested a whyle for his avayle;

And dranke of that water his fyll;

And then he lepte out, with good wyll,

And with Morglay his brande

He assayled the dragon, I understande:

On the dragon he smote so faste,

Where that he hit the scales braste:

The dragon then faynted sore,

And cast a galon and more

Out of his mouthe of venim strong,

And on syr Bevis he it flong:

It was venymous y-wis.

This “rested a whyle” rings the bell of “stood awhile in thought” from Carroll, and falls at exactly the same place dramatically, in the calm before the storm of dragon-battle. These lines come from ballad of Bevis of Hampton, which seems as likely as anything to have been a model for Jabberwocky. Yet in all of google books I find nobody even mentioning them both in the same text. Indeed, I only find one person who even identifies the link to “Percy’s Reliques” — and it’s someone writing on the Reliques who mentions Carroll in passing, rather than the other way around.

Most authorities just seem to say that Jabberwocky is a parody of Beowulf, I assume because they’ve heard of Beowulf. Come on, people! Haven’t academics and obsessives been picking over this territory obsessively for 150 years? What have they been up to, if not this?

And my goodness, look at this! For $300 Lewis Carroll’s own personal copy of the Reliques can be yours???!!!???!!! Gosh, I wonder if there are any telling pencil marks in there!!

Seriously, where is everybody???

One more thing. Ever since I was a kid I’ve wanted to know: why give a poem about a creature called “the Jabberwock” the title “JabberwockY,” with a Y appended? This must be in imitation of some specific linguistic model, but I am unable to identify it. “Jabberwockiad” I would at least recognize. Unfortunately the Jabberwocky academic establishment has once again thoroughly failed me.

Thoroughly convincing research. Well done.

I’m sold.

The “Y” making “Jabberwocky” does remind me of something else in that format…I’ll keep thinking.

I thought of it:

amphigory

(the basis for “Amphigorey,” but a real word first used in 1809)