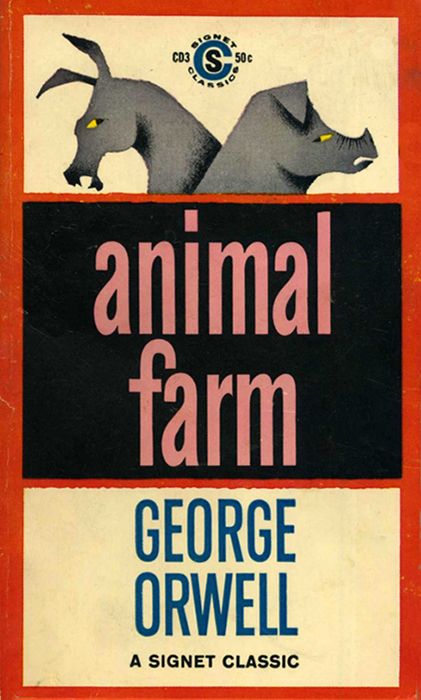

CD3, 50¢, August 1959. Cover artist unknown. 128 pp.

This remarkable book has been described in many ways — as a masterpiece… a fairy story… a brilliant satire… a frightening view of the future. A devastating attack on the pig-headed, gluttonous and avaricious rulers in an imaginary totalitarian state, it illuminates the range of human experience from love to hate, from comedy to tragedy. “A wise, compassionate and illuminating fable for our time… The steadiness and lucidity of Orwell’s wit are reminiscent of Anatole France and even of Swift.” — NEW YORK TIMES

With an Introduction by C.M. Woodhouse

Yeah! A classic that you can read in two hours! In and out!

This is a brilliant conception, cleanly executed. But it’s not half as timeless as people want to believe. The fabulist trappings seem to imply that a universal truth is being illustrated, but really it’s just a big political cartoon: the pigs could be wearing block-letter captions that say “Marx,” “Trotsky,” “Stalin.” So now that Stalin is long dead, what’s really the message for a modern reader? Does the book make the case that such pigs will always arise? Or just that one did, in that instance? We find in it what we want to find. One so wants it to be about the inevitable decay of revolution into tyranny… despite the fact that the way it’s constructed, it’s not about inevitabilities; it’s about personalities.

And even that only superficially. Why is Napoleon the Stalin-pig such a thoroughgoing tyrant? Why all the self-serving lies, the paranoia? What drives him? And what could have been done about it? The book doesn’t go there. Orwell’s intentions are more political than philosophical; he’s too furious about the state of affairs to really investigate the questions of porcine nature that ought to drive the thing. His purpose is just to call something out. “Hey, pay attention, everybody: this can happen, and in fact has happened.” Bigger claims aren’t made because it’s not at all clear that he would have wanted to make them. Everyone remembers that the book is anti-Stalinist but I think people tend to forget that it’s also more or less pro-socialist — as Orwell was. The whole thing hinges on a fundamentally Marxist metaphor, after all: that the working classes are to the bourgeoisie as farm animals are to farmers. Once you’ve nodded at that you’re already pinko.

I was very much with it, thrilling to the slow creep of tragedy, right up until the moment when Napoleon/Stalin emerged from the shadows, seized power and violently drove out Snowball/Trotsky. Suddenly the tragedy was no longer inevitable or cautionary: there was a shameless villain on the scene, on whom all future degradations could be blamed. I wanted to see ideals get eroded from within; I wanted to be shown that revolutions are psychologically insufficient, that the injustices of the social order cannot simply be opposed and conquered, because they continue to live deep inside the minds and expectations of the people. Instead I just got to see what happens when a bad guy takes over. I already knew what happens.

Not to say it wasn’t scary reading, at this particular historical moment. Oh, it’s scary, all right. I know I’m pretty resolutely anti-political on this blog, but let it not be thought that I’m so oblivious as to be able to read Animal Farm now without certain stuff coming to mind. People have been talking about 1984 seeming eerie and prescient and apropos, but this book seems to me even closer to what we’re watching on the news. The ruling monsters aren’t a massive techno-conspiracy; they’re sloppy and stupid and paranoid and shortsighted, a bunch of pigs driven by the pettiest vanities, playing with things they don’t understand, covering their asses in only the most absurd, infantile ways. And it seems to be working out for them.

I read this as a kid because the premise appealed so strongly. As did the tone of unrelenting deadpan. Charlotte’s Web as Lord of the Flies — of course I wanted to read that. But I remember the actual experience being frustrating. The book starts and ends as it should, I felt, but the stuff in between left me cold. Now I see that it’s because I didn’t know Russian history. I would have been incredibly dismayed to learn that it was a prerequisite. I guess I still find it disappointing. Couldn’t he have aimed higher and wider?

The book I imagined, the one I was hoping for — the one I think most people forcibly extract from this one and remember this one to be — is a better book. That book doesn’t quite exist. I can’t imagine that American public schools would be nearly so quick to assign this if they really thought it through and recognized it for what it is: a tract by and for Western socialists. But of course since it only takes two hours to read, it’s not too hard to hold on to the imaginary book you want it to be, as the real one zips by. Before you know it you’re alone with your imagined book again, undisturbed by Mr. Orwell. He mostly plays along, after all.

Excerpt:

Suddenly, early in the spring, an alarming thing was discovered. Snowball was secretly frequenting the farm by night! The animals were so disturbed that they could hardly sleep in their stalls. Every night, it was said, he came creeping in under cover of darkness and performed all kinds of mischief. He stole the corn, he upset the milk-pails, he broke the eggs, he trampled the seedbeds, he gnawed the bark off the fruit trees. Whenever anything went wrong it became usual to attribute it to Snowball. If a window was broken or a drain was blocked up, someone was certain to say that Snowball had come in the night and done it, and when the key of the store-shed was lost, the whole farm was convinced that Snowball had thrown it down the well. Curiously enough, they went on believing this even after the mislaid key was found under a sack of meal. The cows declared unanimously that Snowball crept into their stalls and milked them in their sleep. The rats, which had been troublesome that winter, were also said to be in league with Snowball.

Napoleon decreed that there should be a full investigation into Snowball’s activities. With his dogs in attendance he set out and made a careful tour of inspection of the farm buildings, the other animals following at a respectful distance. At every few steps Napoleon stopped and snuffed the ground for traces of Snowball’s footsteps, which, he said, he could detect by the smell. He snuffed in every corner, in the barn, in the cow-shed, in the henhouses, in the vegetable garden, and found traces of Snowball almost everywhere. He would put his snout to the ground, give several deep sniffs, and exclaim in a terrible voice, “Snowball! He has been here! I can smell him distinctly!” and at the word “Snowball” all the dogs let out blood-curdling growls and showed their side teeth.

The animals were thoroughly frightened. It seemed to them as though Snowball were some kind of invisible influence, pervading the air about them and menacing them with all kinds of dangers.

Yup!

Progression of the Signet edition. Note that this section is particularly long because this baby, along with 1984, was Signet’s bread and butter for decades. The book isn’t in the public domain, and the Signet edition is more or less the preferred edition, certainly for schools. Selling this thing in quantity was undoubtedly a vital part of the New American Library business model. Hence the careful attention to its pricing over the years, evidenced by these many many incrementally inflated new editions:

CP121, 60¢, 1962.

CT304, 75¢, 1965.

First a couple more prices still with the cover design as above.

CQ605, 95¢, 1972.

CY749, $1.25, 1974.

CW1028, $1.50, 1977.

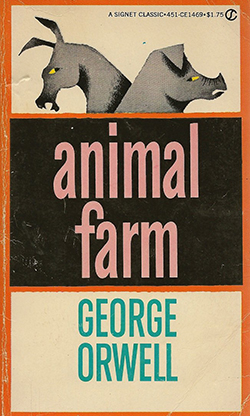

CE1469, $1.75, 1980.

CJ1679, $1.95, 1982?

The same design with minor adjustments for the new branding.

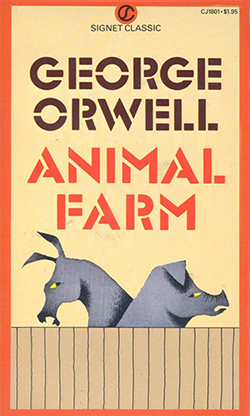

CJ1801, $1.95, 1982?

In the early 80s all the covers get overhauls; this is one of the only instances where the new cover retains the illustration from the old cover. Good call! That illustration is iconic and, I think, pretty much unimprovable. And the new stencil type is inspired. This is what a tasteful update looks like.

CJ1801, $1.95, 1983?

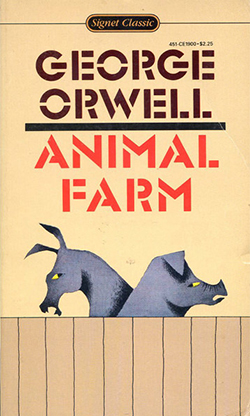

CE1900, $2.25, 1983?

CE2087, $2.50, 1986?

CE2156, $2.95, 1988?

CE2230, $3.50, 1989?

CE2466, $4.95, 1990?

CE2536, price unknown. 1991?

Then soon afterward the series branding is redone, so the design is rejiggered into this version. This lasts most of the 80s and 90s and is probably the most abundant at used bookstores. The copy I read was a CE2156 that looked like this. I approve. This was and remains an excellent book cover, and it well deserves its ubiquity. (The fence looks better with wider boards, don’t you think?)

2634, $5.95, 1996.

Uh-oh, it’s the 90s, mom, and as usual that’s bad news for book covers. The venerable 1959 illustration is being given a none-too-subtle hint that it’s kind of starting to feel “in the way,” if you know what I mean, no offense, and maybe might want to think about looking into one of those nice retirement homes, just a thought. But isn’t it so great that it’s still with us. Yes. Lifetime achievement awards all around.

Meanwhile it’s time to spice things up with a new piece of prefatory material (added to the old), this time by Russell Baker. It’s well done, though it dates itself by asserting as fact that the extreme pessimism of 40s-era literary prognostications about totalitarianism, like 1984, turned out to be “ludicrously wrong” — which he attributes to the authors having far overestimated the efficiency and intelligence of the regimes. How very 1996 of him! I mean, I’d still like to agree with “wrong,” but in this future year 2017, “ludicrously” is starting to sound a little overly brash. We’re still waiting and seeing, I think.

2634, $6.95, ~2000?

50th Anniversary has come and gone.

2634, $7.95, 2004.

Well, they had a nice run, but good old donkey and pig have finally been let go. Because it’s the 21st century and you know what that means: time to take the “classic” out of “Classics.” Now you’re waking up strapped to an operating table after a rough night at Fight Club, you can’t quite remember what happened, and a serial killer is holding a toy in your face. It’s millenial; it’s edgy; it’s raw. It’s Animal Farm, baby.

2634, $9.99, recent.

Okay, we made your book a little taller, because that’s the style these days. That’ll be 2 dollars, ma’am.