2000:  2015:

2015:

directed by Masaki Kobayashi

original stories by Yakumo Koizumi [= Lafcadio Hearn]

screenplay by Yoko Mizuki

Criterion #90, Kwaidan.

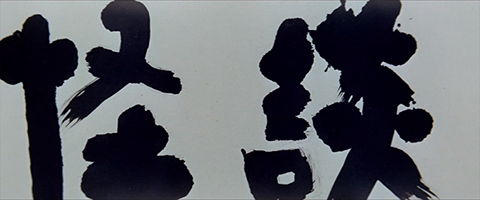

怪談 = kaidan = weird tales.

Kwaidan with the W is today considered an “archaic transliteration” but continues to be the standard title of this movie. Please be advised that the W is not to be pronounced. (But try telling that to the guy who does the commentary.)

怪 = kai = mystery/strangeness/apparition/the supernatural/the uncanny

談 = dan = (as suffix:) story, talk, conversation

If you type “怪談” into Google Translate it gives you “Ghost stories.”

If you type “怪 談” it gives you “Strange stories.”

If you type “怪” and “談” on successive lines it gives you “Monster Consultation” which would be a great name for something, albeit not for this movie. More likely a Sesame Street skit.

If you trace each stroke of those two characters in the title screen above, you’ll get a sense of just how rough and ugly the brushwork is. We’re all used to the “lettering of the beast” effect in English-language horror typography, but we don’t necessarily know how it looks in other alphabets. This is the Japanese version: whoever or whatever it was that put that brush to that paper, it was something other than a master craftsman — what could be more disturbing? Something primal and scary is coming.

The credits that follow are exquisitely printed and laid out with letterpress fussiness, but they’re intercut with the unearthly billowing of ink falling through water. The civilized world cannot stand against the world of the senses. That which is wet, that which seeps under doors, devours all, silent. These gentle bells are going to keep ringing whenever they will, no matter what you try to do, no matter what order your credit sequence tries to impose. That’s the essence of horror.

Even if this isn’t a horror movie as such, it delivers the aesthetic spirit of horror. You may want to draw neat, rigid lines and “know” the world… but something with its own nature, something rough and unpretty, something from before, is coming.

(Namely: feelings.)

This is a fine movie to sit back and have a drink to. It trickles rather than pours. It’s steady, and if you’re sufficiently passive, it caresses you into being steady, seemingly for the sake of respecting the folklore, the careful Japanese tradition of it all. Then once your heartbeat is nice and slow, it uses that space to make you uneasy.

I got actual goosebumps at one point — not common for me as a moviegoer — and it made me think about how my goosebump response is down a slightly different path from direct horror. It’s the path of “suspense,” in the literal sense: the feeling that some unpleasant outcome is suspended, has begun but is nowhere near finished. It’s clear where it’s going; it just hasn’t gotten there yet.

Kwaidan absolutely refuses to speed up. If something eerie or ominous begins to happen, you’re stuck with it for as long as it takes. If a ghost-woman is going to swoop down toward you, that swoop is going to take several seconds. Here she comes: watch. That’s where the goosebumps come in. Your mind might know where things are headed but your body has to live with the present moment, and the present moment may be distressingly long.

The trance effect of the serene. I said something similar about Andrei Rublev. Some emotions can only be touched from within a trance. Both movies share an interest in evoking the national myth, the old world, the world from which the folklore arises. The lullaby quality helps get at primordial feelings. In Tarkovsky’s case the feelings were somewhere behind religious awe; here they’re somewhere behind superstitious fear. Fear in a trance is a whole other emotional territory from anxious, quick, jumpy fear. Rather than your life being at stake it’s your sense of life. Will things go on seeming like themselves?

Kwaidan is like a great-grandfather to modern “J-Horror,” though aside from the standard thematic elements — women’s hair, vengeful spirits, the sea — the connection is mostly in the underlying sense of the gradual and the inescapable. Stasis that exerts pressure, or very deliberate motion that becomes intensely pregnant. I imagine those are aesthetic techniques that extend back into the traditional Japanese theater arts. In cinematic terms it means a lot of crane and tracking shots, smooth, measured. The attention glides forward toward a mysterious figure with its back to the camera. It’s probably going to turn around and show its face now. That’s probably the next thing that’s going to happen. It’s certainly going to happen now.

At the same time Kwaidan is much quieter, more meditative and less purposeful, than a horror movie. It’s painterly, more concerned with the integrity of its own mise-en-scène than with the effect on the audience. It’s compelling because that kind of integrity has force, but the force is in the direction of no particular genre. It’s sui generis; for all its big-budget accessibility, it’s really an art movie.

There are four tales here, running about 40, 40, 80, and 20 minutes respectively. I found the first two the most effective; the long third segment gets the lion’s share of the attention in discussions of this movie but I found it somewhat more demanding on my conscious attention and thus less rewarding to my trance, which wants to remain pure and passive. The lightweight fourth segment has plenty of charm — M.R. James came to mind — but in this company, it doesn’t feel like it’s really given enough time to register.

Recurring theme: the past can’t be denied. The past is not to be trifled with; it’s no joke. In the climax of the first story this erupts beautifully right into the makeup of the protagonist. Existentially unnerving.

Japanese period movies have the fantastically awful tradition of tooth blackening to work with. They get this repugnant visual for free because it’s historically accurate! Hollywood can only envy such a gift. Yeah, sure, in a western, the old prospector can grin and be missing most of his teeth, but seriously, who cares? So what? That’s nothing next to the impact of a wealthy noblewoman coyly parting her lips to reveal a sickening horror.

The problem of “what to do with folk” is one of the major recurring themes in 19th and 20th-century art. Kwaidan is a difficult movie to categorize by genre in great part because it answers that question with such distinction. This is a genuinely original cinematic approach to the challenge posed by folklore and it results in a unique artistic product. The idiosyncrasy arises, in part, from Japan’s particularly acute sense of modernity fighting it out with tradition — note how the trailer assumes that it will be crowd-pleasing to brag that the movie is “the essence of the Japanese, revived here as a protest to modern society.” Hard to imagine an American movie ever playing that angle. Not overtly, anyway.

That said, the overall aesthetic vision here, of a traditional tale treated as raw material to be cranked through the mechanism of an archly stylized production, all shot on entrancingly artificial sets, reminded me of the Jim Henson Storyteller. And those color-saturated “exteriors” against huge surreal painted backgrounds, under studio ceilings unseen but felt, suggested the weird interior/exterior spaces of Hollywood dance or dream sequences. Those giant eyes in the sky are right out of Dalí’s work on Spellbound.

The whole lavish production is just a pleasure to take in. And Kobayashi’s fluid camera technique is consistently engaging. I’ll admit that there were moments when the deliberate pace left me without any real drama to savor, but I was never without something to see. And hear — see below.

But first the bonus stuff. I watched on FilmStruck, which offers all the supplements from the 2015 disc. Thanks, FilmStruck!

• New 2K digital restoration of director Masaki Kobayashi’s original cut, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

The restored image looks spectacular; the balance of the 60s palette is wonderful. Apparently the Criterion edition that was available up until 2015 was a cut version of the movie and didn’t look very good. Just another reason to be glad I’m moving so slowly through this project.

• New audio commentary by film historian Stephen Prince

It’s okay for a one of those, but it’s definitely a one of those. Did Kobayashi have political allegories in mind when he put those eyes in the sky? Who knows. All I know is, Stephen Prince didn’t convince me that he did; he just convinced me that a film scholar type might try to say that he did. A lot of compositions are described as we’re looking at them (“The vertical tree bisects the image”). He talks a fair bit about “the Z-axis,” which just FYI is “the axis orthogonal to the picture plane.” Etc. And three hours is a lot, for that sort of thing. (Though I appreciate that Professor Prince also affords himself room to make sincere doofus comments, like pointing out that if the priests had shown “a little more hands-on attitude and follow-through” they could probably have saved Hoichi from his fate. It’s true!)

• Interview with Kobayashi from 1993, conducted by filmmaker Masahiro Shinoda

This is pretty good. Kobayashi is wearing his regulation “old man” hat and sunglasses, and you can really hear every smack and grumble in his throaty old man voice. He smokes a cigarette as he mutters in shop-talk mode about the production’s financial problems. We watch such interviews for a sense of the human encounter and I got that.

• New interview with assistant director Kiyoshi Ogasawara

Nothing particularly interesting to say, but he was there, and he was involved in the restoration process, so sure.

• New piece about author Lafcadio Hearn, on whose versions of Japanese folktales Kwaidan is based

This is the strongest bonus feature. The interviewee is Christopher Benfey, who has a very good enthusiastic professor manner and gives a nice miniature talk that actually feels relevant to appreciation of the movie. Recommended.

• Trailers • New English subtitle translation

GREAT STUFF

• PLUS: An essay by critic Geoffrey O’Brien

Not bad, actually.

Toru Takemitsu is a very big name as both a film and a “serious” composer, so I was looking forward to seeing what he’d do, but I had no idea just how much this movie was going to be The Toru Takemitsu Show. What he’s done here is highly conspicuous, and truly brilliant; I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anything quite like it and indeed I wonder if there’s anything else out there that can compare.

“Music and sound effects by,” it says, and the brilliance lies in the fact that the two are made absolutely equivalent. The soundtrack is treated as a single continuous texture. Sometimes we hear the snapping of wood when we’re watching wood break on screen; elsewhere we hear the same sound simply as expressive percussion. The slight unreality of bad Foley work, subconsciously familiar to every moviegoer, the subtle gap between a sound effect and its purported source, is here pried open like a coffin out of which ghouls escape. At the end of the first episode, when the samurai is beset by horror and escapes over crumbling floorboards, we hear the expressionist musical equivalent of all his shrieks and stumbles, in electronically manipulated quasi-musical sounds, but we do not hear anything directly from his world. The effect is intense and terrific. Takemitsu tries variations on it throughout. A horse’s hooves remain onscreen but their reality is gradually submerged into dream-juxtaposition as their sound, already artificially rhythmic, is gradually replaced by the clack of a loom — or is it just the avant-garde thunking of the prepared piano? Or what’s the difference, really?

Part of what’s so wonderful about this approach is that it primes us to perceive an unearthly musicality even in scenes with no “musical” content. In the fourth episode when our protagonist waits by a ticking clock, the rhythmic ticking of the clock can’t help but take on a distinctly musical intensity. Or the girls playing paddleball outside the writer’s house. Clack. Clack. By that point the film has taught us that things are not merely themselves; they resonate in the spirit world, which may not always be visible but is always audible. All sound, in this film, is less diegetic than it might be.

As is the silence. This is the most carefully silent movie I’ve ever seen. I’ve always enjoyed the unexpected transcendence of the moment in Duck Soup when suddenly the audio drops to absolute silence for the mirror sequence. A true silence is a powerful effect, and Takemitsu and Kobayashi do more with it here than I’ve ever seen done. Just watch the opening shots of a spooky abandoned house, scored by a few clicks and a lot of pure silence, and immediately experience something special.

Takemitsu was an experimentalist in the broadest sense, which is to say that for him, avant-gardism like this was itself just an experiment. Some of his music is extremely conventional. The rest of it falls freely in the expanse between. He wrote some 100 film scores but I gather that he considered this one his proudest achievement in the medium. In a way this movie makes the best possible case for the aesthetic world of John Cage and musique concrète; the skeptical viewer immediately has intuitive access to ideas that would otherwise seem esoteric.

Our selection is the Main Titles. “Theme from Kwaidan” you can call this. (Yes, it’s playing. Give it at least 16 seconds!)

Given how vital silence is to this film, the comings and goings of the ever-present hiss — which are surely the byproduct of some kind of computerized attempt at noise reduction — are unfortunate. When I first listened I really believed that the title music consisted of bells and sounds of the ocean. But the soundtrack as released on record — the whole score tastefully condensed by Takemitsu into a 27-minute suite — makes clear that this is not the case. It’s just meant to be bells and silence.

So, hey, “new 2K digital restoration” restorators: that’s not really what I’d call top-quality silence. It’s not the kind of premium silence I’ve come to expect from Criterion.