2000:  (OOP 9/2005)

(OOP 9/2005)

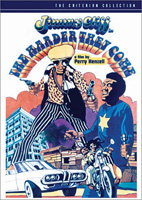

directed by Perry Henzell

written by Perry Henzell and Trevor D. Rhone

Criterion #83.

(This trailer has been transferred 5% too fast. The same song is posted below at its proper pitch.)

On Criterion’s site, one of the user comments about The Harder They Come says that it “feels more like folklore than film.” That’s aptly put, and the phrase lingered in my mind during my time with the movie. The distinction it makes is real, but it’s also relative; you can feel the shift by degrees as you walk through an art museum from, say, the “19th century European” galleries to the “medieval European” to the “ancient Egyptian” to the “Pacific Islander” galleries. Things start to seem more essentially sociological than aesthetic, “more folklore than film,” as they become more culturally distant from you.

Art is made by and for communities, and I only belong to a few communities. That puts limits on how much art is accessible to me. When I’m at the museum looking at ancient Chinese sculpture or Greek pottery or Polynesian idols, I understand very well that I’m only a tourist, peering in on someone else’s business from far, far away. I can speculate about what it was to them, or I can let it be whatever it happens to be to me. But I can’t “just get it,” which is the truest form of artistic experience. That’s a privilege exclusive to those for whom it was made.

The Harder They Come is a movie for Jamaicans of 1972. It is for me about as much as Seinfeld is for them.

1. I can speculate about what it was to them.

There had never been an indigenous Jamaican movie before. Suddenly they got to see themselves. They got to see that the inherent glamour of cinematic space and time was accessible to them, was applicable to their lives, their language, their world. I’m generally pretty cynical about “identity politics,” but there’s no denying that at its core is something real and important: everyone sees themselves in a cultural mirror, and everyone’s sense of self-worth is affected by what they see there. Film is intrinsically a mirror of glory: I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me. It’s one of the greatest affirmations a community can give itself.

From the commentary track, here’s director Perry Henzell (a white Jamaican, born into and then disowned from an old plantation-owning family) talking about the movie’s premiere. He’s referring to the very first shots of the movie, in which a bus — see the title screen above — travels down a narrow seaside road and gets blocked by oncoming traffic:

The audience came to the theater and then at this point, where the bus [has to brake], they went mad. … Right at the start, this whole thing is so familiar to Jamaicans. This business of two trucks coming together and one won’t move, you know. The opening night was in Kingston at this big old theater that we had there, 1500 seats, called the Carib Theater. It was just, you know, crowd as far as you could see. And they beat the doors in and rushed the theater. And invited guests… I mean, the prime minister’s wife was sharing a seat with the prime minister’s mother, that kind of thing — she’s in the film, actually — three people to every seat. And they just started screaming. And I never — tell you the truth — never heard another word of dialogue that night.

There is no thrill in moviedom like people seeing themselves on the screen for the first time. Jamaicans had never ever seen themselves on the screen, their lives represented on the screen. The first time that it happens it produces this unbelievable audience reaction, like nothing else ever could.

This is not to imply that The Harder They Come is a simplistic film catering solely to the most primitive needs; taken as a societal self-portrait it’s actually pretty worldly and layered.

Based roughly on the career of a real-life celebrity criminal, it’s a film that follows the standard “antihero” formula: letting the audience vent their resentments and “know better” at the same time.

Jimmy Cliff’s “Ivan” is a ne’er-do-well wannabe singer whose ambitions are so frustrated by the exploitative music industry and the everyday realities of Jamaican poverty that he eventually drifts into becoming a murderous outlaw, vaguely entangled in the “ganja” trade. His infamy turns him into a folk hero and his song becomes a hit. He embarrasses all the petty authorities by the swagger with which he outruns and outguns them; the harder they come, the harder they fall — at least in the fantasy he’s trying to live out. The mass audience within the film, as outside it, roots for his rebellious violence against the whole corrupt system, roots for his single-minded commitment to the poor man’s dream of being someone who counts, a celebrity, a big shot. Then he gets inevitably gunned down, like Butch Cassidy or Bonnie and Clyde; this, too, is what he and the audience expect and want.

The final shootout is actually intercut with shots of raucous, delighted Jamaican moviegoers. In one sense, these are the admirers in Ivan’s head, the imaginary audience for whom his whole spree has been a performance. In another sense they are the actual society within the movie, living vicariously through his criminal exuberance. And at another level they are a nod to the actual audience actually watching this actual movie: the mirror of art brought to an absolute head, a depiction of the viewer in the moment of viewing. It’s like the movie ends by cheering for itself; the whole thing has been a cheer, simultaneously cynical and heartfelt.

But I, here in the USA in 2016, am way, way on the outside of that cheer. Trying to imagine that I am on the inside is just an exercise. It will never be an aesthetic immediacy, for me.

2. I can let it be whatever it happens to be to me.

Unfortunately that’s not very much. I can appreciate that the Jamaican accent and speech patterns and attitude are warm and melodious, but the whole manner makes me disengage; it feels somehow like nobody thinks anything they’re saying or doing really matters. I know that’s not the case, but I can’t deny that it’s how my American ears process it.

It’s not a film by or for primitive minds, but it is a primitive film by any normal technical standards, performed by unskilled non-actors and with all the hallmarks of a very low budget. These kinds of factors are significant not because expensive sets and lights and performers have cachet in themselves, but because the more advanced the execution, the more universal the product. Just as money is a universal standard for value, the things money can buy tend to enable communication in more universal terms. A cheap little third-world movie like this has to rely fundamentally on the existing human value-exchange systems of its particular culture. That’s not at all a bad thing, but it is a boundary.

Both literally and figuratively, I have a hard time understanding these people, and the movie isn’t speaking in any voice other than the voice of these people. It can’t afford to and it doesn’t want to anyway.

In the commentary, Henzell talks about his interest in capturing real things on film as they are, and not constructing sets or hiring trained actors. He says proudly that a scene in a Kingston arcade was shot simply by walking in and filming whatever was really going on there that night. That kind of access is of value to me, and it’s true that this film is built out of such footage; it lets me experience places and people that I would never otherwise experience. When I saw the arcade scene the second time, while listening to the commentary, I thought, “yeah, he’s right, it’s fascinating to get to take a virtual stroll into this place and check out what’s going on.” And yet in the course of watching the movie I hadn’t been able to appreciate that, because it had told me it was a story, and I was trying to watch it that way.

Had the same footage been presented as a documentary I would have been able to get so much more out of it. Every film is, in an esoteric sense, a documentary about what was really going on in certain places at certain moments. The question is whether the film indicates, by its body language, that this way of watching is intended, is desired. Black Orpheus, which has a lot in common with The Harder They Come, made very clear to the audience that it was offering a poetic form of virtual tourism at least as much as it was offering fiction. The Harder They Come seems in retrospect to have had some of the same intentions, but it didn’t make the gestures. Or if it did I didn’t pick up on them.

I found this movie extraordinarily difficult to get through. It took four or five false starts over the course of a full year before I finally managed to see it through to the end, and even then I was in something of a stupor. There’s something stupefying about it, exactly as there is something stupefying to me about the anthropological rooms at the art museum; I can only look at Polynesian idols and Greek pottery for so long before I exhaust the spontaneous artistic response they provoke in me and become aware of myself standing in a room alone with some “interesting” objects. They are not mine and I am not theirs; that’s okay. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. We can’t all be one another’s.

I have borne this “interesting” film with me for a year and have now finally fulfilled it.

I wrote everything above before finishing the commentary. Here’s something Perry Henzell says at the very end:

It’s two movies, Harder They Come, two totally different movies. In Europe and America and Japan, it’s a movie for college audiences who are sophisticated enough to want a glimpse into another world. In the other world that they’re glimpsing into, like Brazil, Africa, Caribbean, and so on, it plays to people who, you know, are poor people living in slums, living in the conditions that the movie represents, and it plays like Kung Fu.

I guess I will try to hold it as a point of pride (?) that despite falling squarely in the first demographic, I nonetheless instinctively tried to watch the second movie. And failed.

In America, the most lasting mark left by this movie is that its soundtrack was decisive in introducing reggae to the masses, much like what the soundtrack of Black Orpheus had done for bossa nova.

There’s no instrumental underscore, just songs. The obvious choice for our selection is the title song, which we get to watch sung live in the studio, in its entirety. From the commentary we learn that this was the first time the song had ever been performed.