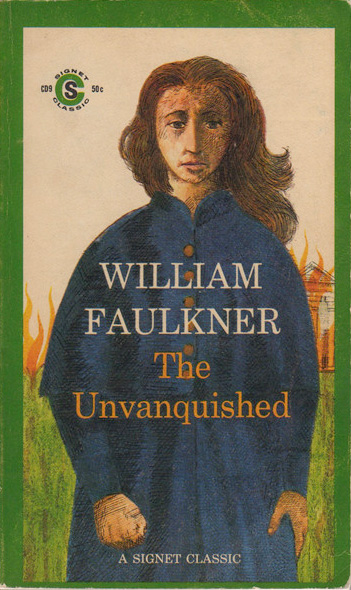

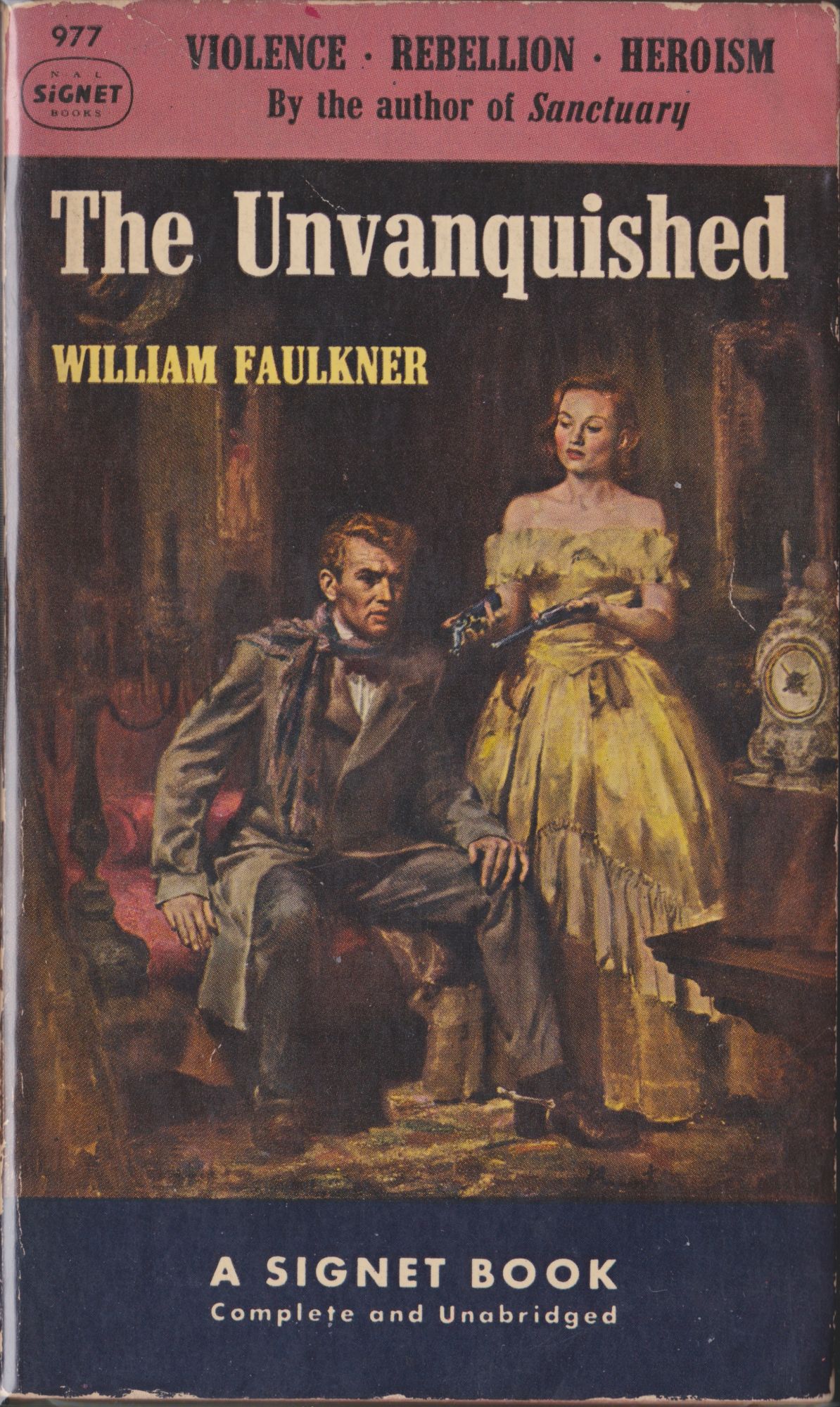

CD9, 50¢, August 1959. Cover artist unknown. 192 pp.

Set against the backdrop of the chaos of the Civil War, this is the magnificent story of the proud Sartoris family, who lived with violence in order to survive. But it is particularly the account of how young Bayard Sartoris, well tutored in killing, found the wisdom to decide that there had been enough bloodshed, and the courage to face the enemy alone — and unarmed.

This is one of the most powerful works of America’s Nobel Prize-winning author, one which lends insight into his other books and illuminates Faulkner’s credo: “Man is tough. Nothing — war, grief, hopelessness, despair — can last as long as man himself can last; man himself will prevail over all his anguishes, provided he will make the effort to stand erect on his own two feet by believing in hope and in his own toughness and endurance.”

With a Foreword by Carvel Collins

Vanquished, finally. Only took me a year.

One sees it said that this book makes a perfect introduction to Faulkner, because (to quote from this edition’s foreword) “the central idea of the novel is obvious, its style relatively simple.”

Thus encouraged, I began. To my dismay I found that the central idea of the novel was not obvious and the style was rather difficult.

No matter how carefully I parsed the ostentatiously roiling sentences (these, the ones I read, the only ones) which carried in defiant repose the stubborn insignia of that uncertainty which marks every sorrowful recoil of comprehension, every insistence that these, the sentences we are reading, are the ones, the ones of which we’ve heard old men speak but never read for ourselves, except that their voices (the voices of the old men) were only voices, echoes of some forgotten calumny no more real than General Lee, once as solid as the land over which he ranged, furious in retreat, is real (to us, to me), now just a whisper, an insinuation.

Ahem. I was saying: No matter how carefully I parsed the ostentatiously roiling sentences, the book as a whole remained mysterious, a sequence of peculiarly overwritten events of no clear import. I could tell that something insistently Southern was playing out behind a scrim of prose, but I couldn’t pick up any guiding scent of tone or plot. Uh-oh, sounds like a classic case of Faulkner after all.

Yet when I went opinion-gathering, it seemed like every Goodreads Moe and YouTube Larry was blithely reporting that this was a GOOD BOOK ABOUT A BOY WHO GRWOS UP, ITS EXCITING, I LIKED IT. The discrepancy made me uneasy.

I crawled all the way to the middle of the last chapter, and then life happened to break my rhythm and the book was set aside with about twenty pages remaining. When I picked it up a few months later, it was oddly clear and simple. Apparently I hadn’t really read any of it yet, because I hadn’t known how, whereas now I was ready to read it properly. So I started over, and found that it had become a whole other book, about a boy who grwos up, in which the central idea was obvious and the style was relatively straightforward. And I enjoyed and admired it. Somewhat.

I think the problem boiled (and, I daresay, boils) down to this:

There are seven chapters, of which the first six were originally written as middlebrow magazine stories: five for The Saturday Evening Post and one for Scribner’s. These stories were always intended to be serial and cumulative, but they don’t give the impression of having been planned to form a novelistic whole. Faulkner was fictionalizing episodes from his grandfather’s childhood, and he seems to have been following a biographical sequence rather than a literary one. Only in the fifth and sixth stories does a “central idea” start faintly to suggest itself.

In the final chapter, newly written for book publication, he does a remarkable job of retroactively crystallizing the preceding stories into a novel, by casting them all as prologue to the coming-of-age that plays out in the last few pages. That’s how bildungsroman works, and once you get there, he does seem, in retrospect, to have written one. I can’t deny that I closed the book feeling that I’d read something good after all, something of genuine literary power. But it’s this element of retroactive intent that, to me, made the book less rewarding to read than to have read. Only through the lens of the last few pages does the book seem coherent and purposeful and straightforward; until you get there, you’re swimming in crosscurrents. I think that may mean it’s a trick.

In addition to adding the last chapter, Faulkner tried to backdate his ambition by touching up the preceding stories, mostly by inserting new passages of conspicuously higher literary tone. This creates a strange effect. Intellectual heavy weather incongruously clouds your view of The Saturday Evening Post on some pages but not others.

Example. Here’s the opening paragraph as it appeared in The Post:

Behind the smokehouse we had a kind of map. Vicksburg was a handful of chips from the woodpile and the river was a trench we had scraped in the packed ground with a hoe, that drank water almost faster than we could fetch it from the well. This afternoon it looked like we would never get it filled, because it hadn’t rained in three weeks. But at last it was damp-colored enough at least, and we were just about to begin, when all of a sudden Loosh was standing there watching us. And then I saw Philadelphy over at the woodpile, watching Loosh.

“What’s that?” Loosh said.

And here it is in The Unvanquished, having been thoroughly sprayed with silly string:

Behind the smokehouse that summer, Ringo and I had a living map. Although Vicksburg was just a handful of chips from the woodpile and the River a trench scraped into the packed earth with the point of a hoe, it (river, city, and terrain) lived, possessing even in miniature that ponderable though passive recalcitrance of topography which outweighs artillery, against which the most brilliant of victories and the most tragic of defeats are but the loud noises of a moment. To Ringo and me it lived, if only because of the fact that the sunimpacted ground drank water faster than we could fetch it from the well, the very setting of the stage for conflict a prolonged and wellnigh hopeless ordeal in which we ran, panting and interminable, with the leaking bucket between wellhouse and battlefield, the two of us needing first to join forces and spend ourselves against a common enemy, time, before we could engender between us and hold intact the pattern of recapitulant mimic furious victory like a cloth, a shield between ourselves and reality, between us and fact and doom. This afternoon it seemed as if we would never get it filled, wet enough, since there had not even been dew in three weeks. But at last it was damp enough, damp-colored enough at least, and we could begin. We were just about to begin. Then suddenly Loosh was standing there, watching us. He was Joby’s son and Ringo’s uncle; he stood there (we did not know where he had come from; we had not seen him appear, emerge) in the fierce dull early afternoon sunlight, bareheaded, his head slanted a little, tilted a little yet firm and not askew, like a cannonball (which it resembled) bedded hurriedly and carelessly in concrete, his eyes a little red at the inner corners as Negroes’ eyes get when they have been drinking, looking down at what Ringo and I called Vicksburg. Then I saw Philadelphy, his wife, over at the woodpile, stooped, with an armful of wood already gathered into the crook of her elbow, watching Loosh’s back.

“What’s that?” Loosh said.

Clearly he’s trying to install an upgrade. No longer a mere Saturday evening story: now it’s a LITERARY NOVEL! Possessing even in miniature that ponderable though passive recalcitrance of prose which outweighs readers.

I’m of two minds about this sort of stuff. The thoughts themselves are generally worth something — I like the image of make-believe as “a cloth” that children deliberately hold up between themselves and frightening things (devised to foreshadow a literal hiding-behind-granny’s-skirts situation later in the chapter, but I appreciate it in its own right) — and Joyceanisms like “sunimpacted” have a clean rhythm that give the scene some feeling of dimension. But what are we to make of the other rhythm, the rhythm of excess? All the needless reiterations (“appear, emerge”) and parentheticals (“which it resembled”) and barrages (“recapitulant mimic furious”)?

What the extra verbiage conveyed to me, when it conveyed anything, was a sense of desperate paddling, the constant struggle to keep above the onrushing waters of truth and memory and experience and life and so on. “It’s all too much, it’s all so overwhelming and nameless, but I am trying, trying, trying to keep it in order, trying to at least name it, to know it, these, the things, comma, comma, gasp, comma, this, these.” And I can find that moving. In the end I did find the book moving in just that way.

But that frame, where being alive means being knocked back by a great wave of strange poetry, coexists very oddly with bits of Saturday Evening Post local color comedy a la Twain, about how Granny oh she was quite a character, let me tell you, get a load of this. Is life conventional and cozy, or esoteric and unknowable? Some combination, of course, and I like the idea that art embraces both at once. But I didn’t feel like Faulkner was truly managing that tension for me as an artist. He seemed to be simply operating in different modes as his moods and ambitions fluctuated.

Even having come this distance, I retain my initial impression of a peculiar vagueness in the dimensions of plot and tone. What would you say is the tone of the passage above? Thought has been lavished on a moment, this is clear, but what is the temper of that thought? Within what feeling does this work emerge? What is this guy into?

As I often say in these posts: art is a social encounter. There’s somebody there. This book was an encounter with someone who was talking a great deal yet never making eye contact. His speaking style was quite florid and intense, but his voice didn’t actually sound particularly emotional and he gave no indication of knowing that anyone was listening to him. It was, for me at least, not socially normal. Perhaps he was drunk. (And indeed perhaps he was, yes?)

Faulkner returns over and over to the device of having the characters fall asleep without realizing it, right in the middle of a paragraph. Time and reality become suddenly muddled and they have to sort it back out. This is indeed a defining experience of childhood and I understand its attraction to him, as a way of reinforcing the premise of his style: the twisty prose is all in that spirit of perceptual defamiliarization, of “who what and where am I, again?” That said, it did seem conspicuous to me that in every single chapter our narrator “must have fallen asleep because I was picturing trees and then Ringo was shaking me awake” etc. etc. The evocation of existential mystery ought not to be so conveniently repeatable.

Oh, the book? Eh, it’s sort of Gone With the Wind does A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and then when it finally finds its story footing in the last act, there are shades of The Godfather — about the grim family culture of vengeance, cavalleria rusticana, and the young man who may or may not manage to shake it off. The prose is sometimes brilliant and forceful, sometimes tangled and rhythmless and underedited. Sometimes both.

It had a distinctive aroma to it. Not a particularly fresh or appetizing one — some rot and barnyard notes — but a striking one all the same, and one I can still call up in memory. And despite my frustrations with the reading experience, I think that has to count as artistic success. What are we here for if not to expand our store of aromas?

And that’s all I have to say about that! I broke protocol and proceeded to the next book before finishing this post; it’s now been months since I read it and there other books piled up in the rear view, yet to be addressed. So this is plenty. Onward!

Onward, that is, after the dessert. IT’S COVER TIME!

Once again, the artwork apparently had to be re-photographed and recolored after the first few printings. (Points of issue: the right side of the burning house is cropped out of the first printing, visible on later printings; the divide between the flaps of the coat runs between the “L” and “A” of CLASSIC on the first printing, straight down through the “C” on later printings.)

This is the last of the shoddy anonymous illustrations that characterized the very first batch of Signet Classics. Next time we’ll have some properly skilled draftsmanship by an illustrator who actually signed his work.

For now… what exactly are we looking at here? There are only two female major characters in the book, Granny and Drusilla, so this must be one of them, and yet it is assuredly neither of them. Given the burning house in the background, I think it must be intended as Granny, but so poorly conceived and executed that she is unrecognizable in terms of appearance, age, costume, or demeanor. Even without reading the book, you’ll agree that the character “Granny” probably doesn’t look like this, right? And is that a fist clenched in unvanquished determination, or just a passing muffin? Are those eyes glowing fiercely with the will to survive, or are they just ants on an almond? Is that hair blowing in the wind or… okay you get it: it’s not a good drawing.

As for future redesigns, there are none: I find no evidence of any Signet Classic edition of The Unvanquished after the fifth printing of this edition in September 1962. That’s a longer survival than the single printing of Adolphe & The Red Notebook, but still a pretty poor showing. Why was it dismissed? What did it do wrong? I’m really not sure. You might guess that someone decided Faulkner was insufficiently “classic”, but this seems not to be the case: in 1964, after The Unvanquished had already been cancelled, a different Faulkner novel was added to the line, and in 1968 five more.

Perhaps there was some sensitivity to sales numbers (later relaxed on behalf of the long tail), and it just wasn’t performing as well as Animal Farm et al? Or perhaps it was set aside for reissue under another product line that never actually came to pass? (Adolphe did eventually reappear as a “Meridian Classic,” though not until years later.) For now these are my only guesses. Readers may submit additional, superior guesses below.

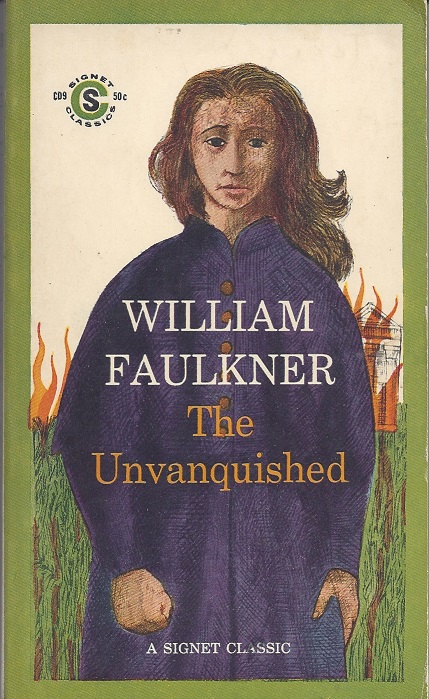

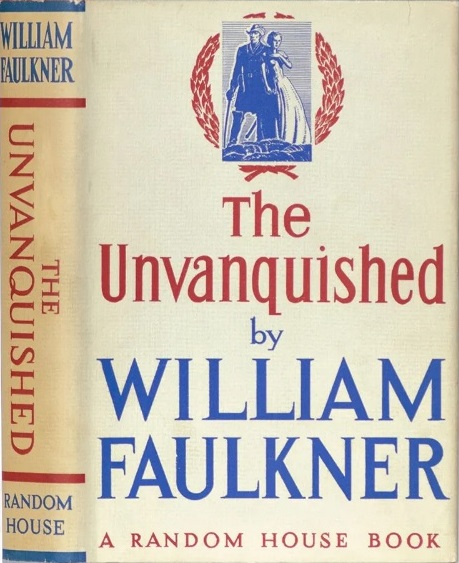

However, there is a PAST redesign! The Unvanquished had already been a Signet before it became a Signet Classic. Perhaps this will bring the marketing experiment of “Signet Classics” more into focus. Between 1952 and 1959, picture this on the paperback rack instead:

Is The Unvanquished an effete art-school stencil-colored line-drawing CLASSIC… or is it a red-blooded bare-shouldered gun-toting oil-painted pulp about VIOLENCE, REBELLION, HEROISM? Great question! We’ll leave it to the consumer to decide.

This time the woman is unambiguously not Granny; it’s Drusilla, in the final chapter, transformed into the seductive incarnation of The South itself, urging Bayard to embrace the way of the pistol. They didn’t look anything like this in my imagination (and probably didn’t in Faulkner’s either), but sure, I grant they could look this way in someone’s well-built fantasy. The painting is not a betrayal of the letter of the text. Aesthetically, though…

I have no problem with the supposed “cheapening” of the work — the pulp sensibility is as legitimate as any other if it can be made to fit the subject — but is this illustration actually inviting? Does it draw you in and make you want to read to find out what’s going on behind that fellow’s troubled stare? To my eye it’s muddy and static; it makes me dubious about the entertainment value of this book. Like so many covers of the 40s and 50s, it looks like something fundamentally dull and awkward has been quickly and carelessly dressed up by the department store studio photographer as something exciting, look over here, say cheese, great, next.

And yet real craft went into this forgotten thing. The more I look at it, the more it intrigues me as a painting, if not as a book. The uncanny cheesecake stasis has an eerie bite to it if you stare long enough. The artist is James Avati (1912-2005), a notable and prolific purveyor of exactly this. His valuation seems to be on the rise of late, as the old low transmutes into the new high. This particular painting doesn’t seem to have made any public appearances since 1952, but who knows, it may turn up at auction any minute.

Here’s a somewhat interesting album of images collected by the author of the book on Avati. I’m not sure whether Avati ever did any Signet Classics proper, but we’ll certainly get to consider more of his work as other pre-Classic Signets make their way into the series.

And finally, here’s the real cover of the real book:

A similar grouping of two figures, but baring decidedly less flesh, probably because of all those dangerously sharp serifs.

I think Edward Shenton’s illustrations in the first edition suit the novel nicely: stark-edged and boldly styled first, emotional second. Here’s how he pictured the exact moment painted by Avati. It too has nothing of the actual flavor of the prose, but it has an analogous spiritual architecture, as it were, and I could imagine it helping to ground the reading experience.

Shenton had also illustrated the original magazine publications, in a suitably lighter-lined style. And hey look, they could be yours to own! Act now!