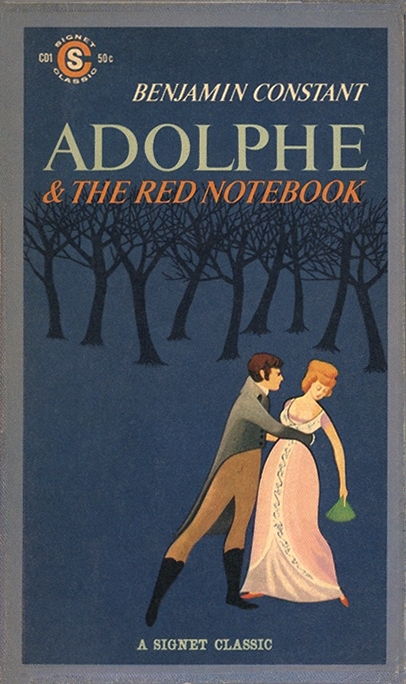

CD1, 50¢, August 1959. Cover artist unknown. 160 pp.

Back cover:

In these two remarkable works, a brilliant, vain, long-suffering Frenchman describes the first twenty years of his life and their culmination in a tortured love affair with an older, possessive woman of the world. Benjamin Constant attempted to conceal the fact that these two books were autobiographical. But to his familiars, it was clear that he himself was Adolphe. And in the intimate account of his strange liaison with Ellénore, he may well have been protesting against his inexorable bondage to his fiery, demanding mistress, Madame de Staël. Constant was an able parliamentarian, a champion of liberalism and the author of the History of Religion. But posterity remembers him as the man who bared the anatomy of a destructive passion in the story of Adolphe.

With an Introduction by Harold Nicolson

I was at The Strand and found a used copy (requiescat in pace Eve Auchincloss) of not the Signet itself but the 1948 edition which the Signet reprints in its entirety. Unlike nearly ever other title in the Signet Classics catalog, this one was never reissued as such, though it seems to have appeared briefly in 1986 as a “Meridian Classic” from the same publisher. (No cover available online.)

I like a little book that grabs one’s attention between its teeth, shakes it roughly a bit, very soon loses interest, puts it down and trots off. A book like an animal wrote it. Benjamin Constant is much too raw and needy to concern himself with any aspirational tedium that would waste my time. He’s got axes to grind; he’s writing as therapy, not for art. He can’t be bothered to pad this thing out. Good, say I.

This is a fine example of a familiar but unheralded genre: real-life confessional self-absorption shamelessly passed off as literary fiction. Examples are submitted daily as “my novel” to uneasy writing teachers the world over. I guess officially we’re supposed to shake our heads at such stuff, but maybe let’s all admit something: when you’re not stuck in a writing class with the author, and don’t have to give reader feedback — or even reader tact — navel-gazing myopia can actually be quite compelling. (“So, yeah, Marcel, I really liked it! Some of the dialogue was really funny! I just… I guess… I would have maybe liked to get a little more information about… the, um, narrator character?”)

Benjamin Constant isn’t really asking for affection, just attention. Fair. And it’s not a marathon, just a novella; it can afford to be one-note. It’s a very peculiar note, so it feels natural that it should get a whole volume to itself — a nicely slim volume. His anti-heroic self-obsession has its own distinctive flavor; it felt new to me, though I guess Knausgaard had a similar quality: he plumbs self-disgust with an ease and confidence that seem quietly to contradict it.

Lord Byron: “it leaves an unpleasant impression.” Indeed it does. In an engaging way. It’s like a piece of sour candy. My genuine thrills of “my god! Adolphe, c’est moi” alternated throughout with “oh for crying out loud.” That kind of alternation is queasy; the line it crosses is a sensitive one for anyone. And so it felt obscurely edifying, even if I have to admit that in retrospect I come away fairly unedified.

People out there will summarize Adolphe by saying that unlike the many books about being in love, this is one of the very few books about being not in love. That’s okay as far as it goes but it sort of misses the point: the book catalogs a series of emotional states in a way that is too agonizingly fine-grained to allow for comfortable application of the concept of “love,” one way or the other. It charts the psychological territory differently.

I’d be interested to read psychoanalyses of Constant. Seems like he would have been interested too. The book is more or less begging for it. And his vaguely Proustian psychological comments seem to me strikingly ahead of their time.

Reading Adolphe I honestly did think I had found something strangely c’est moi more than others. Then “The Red Notebook” — essentially an abandoned memoir draft — recasts the same foibles as a different kind of cringe comedy: an avalanche of absurd profligacy, which made me chuckle and squirm more confusedly. Is this in any way moi? Can I recognize myself in this mirror? Not as readily. God I hope not. “The Red Notebook” seems to be much less often reprinted than Adolphe — it’s really just a fragment — but I found it equally compelling.

Excerpt will be the one I’ve already typed up for several people. But now I type it up for me:

In my father’s house I had adopted, in regard to women, a rather immoral attitude. Although my father strictly observed the proprieties, he frequently indulged in frivolous remarks concerning affairs of the heart: he looked on them as excusable if not permissible amusements, and considered nothing in a serious light, save marriage. His one principle was that a young man must studiously avoid what is called an act of folly, that is to say, contracting a lasting engagement with a person who is not absolutely his equal in regard to fortune, birth and outward advantages; he saw no objection — provided there was no question of marriage — to taking any woman and then leaving her; and I have seen him smile with a sort of approbation at this parody of a well-known saying: It hurts them so little and gives us so much pleasure!

It is not sufficiently realized how deep an impression can be made in early youth by sayings of this sort, and to what extent, at an age when every opinion appears dubious and unsettled, children are amazed at finding the clear rules they have been taught contradicted by jokes which win general applause. In their eyes those rules cease to be anything but banal precepts which they parents have agreed upon and which they repeat to children out of a mere sense of duty, whilst the jokes appear to hold the real key to life.

I also want to bank this splendid phrase: “With the furious courage of a coward in revolt.”

Thumbs up.

PS. Laying this out now for future reference:

In 1948, the American office of Penguin Books separated from its British parent company and became an independent publisher called New American Library. They called their fiction imprint “Signet,” their non-fiction “Mentor” (corresponding to Penguin’s division between “Penguin” and “Pelican”).

The Signet Classics series wasn’t launched until 1959. It received an independent numbering system, beginning here with “CD1.” The C is of course for “Classics” — they’re all gonna start with that — and the “1” is the number of this issue within the Classics series.

The “D” refers to the pricing scheme: back when Signet started out, standard Signets were 25¢ and a few special double-width editions were twice that. Seems like the “D” for “Double” stuck around meaning 50¢ even after inflation had eliminated the 25¢ base price. We’ll also see T for 75¢ and Q for 95¢, which follow similar logic. But then over the years there will eventually also be P for 60¢, Y for $1.25, W for $1.50, J for $1.95, and finally E for all other prices. If anyone has good guesses for what those might stand for, bring ’em.