directed by John Brahm

teleplay by Rod Serling

based on a short story by Lynn Venable

starring Burgess Meredith

with Vaughn Taylor, Ja[c]queline deWit, and Lela Bliss

music by Leith Stevens

Friday, November 20, 1959, 10 PM EST on CBS.

This is the first episode to credit a writer other than Serling. The source story comes from the January 1953 issue of If: Worlds of Science Fiction. In this case, Serling gives credit, because he bought the story outright (for $500) and adapted it faithfully — but all his “original” scripts were just as much indebted to that world of magazine writing, which was at its peak in the 40s and 50s. In coming up with his various storylines and conceits, Rod seems usually to have been operating in the twilight zone that lies between deliberate plagiarism and subconscious influence.

Of course, magazine writing was itself already thoroughly incestuous; sci-fi stories tended to share all sorts of recurring assumptions and preoccupations and tropes. So “plagiarism” isn’t really a fair word to use. And I certainly don’t hold “unoriginality” the least bit against Rod. All I mean to point out is that The Twilight Zone emerges directly from a particular creative culture in which a shared body of ideas had been stewing back and forth for years from writer to writer, a process that tends to mulch things down into their underlying subconscious archetypes. That’s why I think the show merits the kind of reading I’m doing here — because it’s not really one guy’s fantasies; it’s the potent commonalities distilled from among many people’s fantasies, over many years.

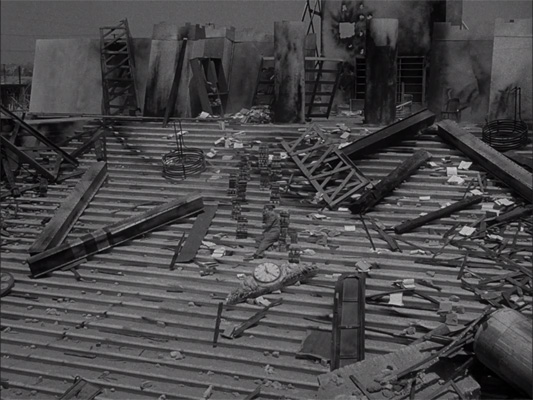

Witness Mr. Henry Bemis, a charter member in the fraternity of dreamers. A bookish little man whose passion is the printed page, but who is conspired against by a bank president and a wife and a world full of tongue-cluckers and the unrelenting hands of a clock. But in just a moment, Mr. Bemis will enter a world without bank presidents, or wives, or clocks, or anything else. He’ll have a world all to himself — without anyone.

We’re all afraid of being this guy: incapable of participating in the social order because of our emotions and enthusiasms.

The conflict between Bemis and society is exaggerated, to the point where we can’t conceive of any possible reconciliation. He is an irredeemably terrible bank clerk; his wife is impossibly unkind. A pitiable fool and a painfully hostile world. This sort of exaggeration is a more promising mode of comedy than any of the series’s previous efforts. It makes absurdity out of angst, rather than of complacency. We fear that there’s no place for us in the world, but this fear is already an exaggeration, so it’s ripe for further exaggeration. Much healthier than exaggerating something quite real and ordinary; to try to stir up shame about, say, the fear of death, as in Escape Clause.

So, thus taken to its extremest, most anxiously catastrophic form, the question being posed here is: if the rest of the world or you had to go, wouldn’t you pick the rest of the world?

Once you and Henry Bemis sheepishly admit that “yes, I think I might pick the rest of the world,” the teacher’s ruler comes down on your wrist, in the form of dramatic irony. How dare you! The whole rest of the world? You monster. Here’s what you and your glasses deserve.

Angst wins the day after all.

This twist ending is, in a way, completely unnecessary to the story itself. If Henry Bemis just sat there reading, out beyond the end of the world, in lonely thick-lensed happiness, that would be plenty eerie enough. In fact, imagining a slow pull-back from that last shot gives me the willies; that would be a much more provocative final image for this very same episode.

But the twist is necessary for completing the standard Twilight Zone two-step: first we dare, and then we pull back from the precipice. Here the thing we dare is subjective indifference — we dare admit the part of us that thinks that “everybody’s dead but me!” might be a relief, might be fun. So then of course we must spin back around and receive the censure we apparently think we deserve. Otherwise we would really disturb some of the audience, which could affect the sales of Sanka.

The idea that the last living human might still be able to experience meaning and pleasure in existence is much more radical and disruptive than the idea that he would surely have any such pleasure arbitrarily whisked away. I mean, Murphy’s Law, am I right? TGIF!

The episode does a good job seeding the glasses. From the start we understand them as being a conspicuous signifier, but entirely within the realm of wardrobe, a zone without words or names. We don’t generally expect such ineffable stuff to graduate to having a role in the story proper. So we feel good and truly “gotten” when the glasses, with which we have developed a strong subconscious relationship, turn out to have their own fate, in the conscious, conceptualized part of the action.

How chastening, for unspoken comfort to suddenly become spoken discomfort! The sting — the reason everyone remembers this episode — is because in some deep way it’s downright embarrassing. “That’s not fair!” Bemis cries along with the viewer. How harsh and humiliating, for both of us, to be reduced to such whimpering, to have all narrative sympathy suddenly yanked away. It’s like being beaten up by a bully who spent the day pretending to be your friend. You don’t forget experiences like that.

The pacing is sort of surprising. Working backward from the iconic ending, you might think that the way to tell this story would be to spend most of the episode demonstrating Bemis’s frustrated yearning to read, and then have the bomb descend near the end and have him go straight to a state of elation at his good fortune. But a subtler math is in play. If Bemis were unreservedly elated at the end of the world, the situation would be so grotesque that there’d be no punch in the final irony — the authorial coldness would already be too complete. That’s not the Rod Serling way. He wants pathos, if he can manage it; he wants this to really smack. So first Bemis’s fear of solitude needs to be established.

“I’m not at all sure that I want to be alive.” “The very worst part is being alone.” Which prompts the question: why did he love reading so much in the first place? What exactly were other people to him? The answer seems to be that he has always had both an individual and a social side, and is now forced to reckon with making a choice between them. The social side is ready to self-destruct, but, seeing the library and being reminded of the joys of being alive, he crawls out from under his vestigial social fear and chooses himself, the individual, who has a chance at happiness. That’s when Fate lashes out. Hell is other people, but “other people” includes Fate. It includes Rod. It can’t be gotten rid of just by getting rid of physical people.

There’s a psychological truth to this. Being physically alone doesn’t mean your mind stops subjecting you to social standards. If you want to sum up the message of The Twilight Zone — and pretty much all supernatural horror ever — you could do worse than: “other people are all in your head — so you can run, but you can’t hide.”

We dare enjoy the fantasy of hiding, but how boldly we dare it varies from person to person. “Time enough at last” means solitude enough at last. And this show is of (and for) an anxious mindset that believes we can never, ever, ever afford that much solitude. Not even after the end of time.

That all said, I feel like there’s a somewhat odd flavor to the moment when Bemis contemplates suicide. It’s a strangely dark note for this goofy character to sound (especially given that we can reasonably deduce that he will in fact follow through, immediately following the end of the episode). The gun makes sense to me mostly as a kind of misdirection, a tragic threat that forces the audience’s sympathies to rebalance. Bemis’s delight at the destruction of mankind would be untenable in itself; but as an alternative to self-murder, it becomes highly sympathetic. (All the better to eat you with, says the irony machine.)

“I’m sure I’ll be forgiven for this, the way things are,” he reasons of his imminent suicide. He’s right — by Twilight Zone logic, he would have been forgiven for suicide, “the way things are.” What he’s not forgiven for being happy the way things are.

“Just a fragment of what man has deeded to himself,” says Rod at the end. On the face of it this is standard cold war grim grandiloquence about The Bomb. But I prefer to hear it as something more basic: I, Rod Serling, hereby deed this nasty ironic twist to myself, and so too do you, the viewer. We do it every day.

Original music by Leith Stevens, an industry fixture who isn’t much remembered today (despite having at one time been so esteemed as to get this plum assignment). This, his one Twilight Zone score, is done in a sort of generic TV style that only points up Bernard Herrmann’s brilliance by counterexample. Stevens fails to stake out his own artistic position and generally just plays the existing action in an ordinary, redundant way. There’s a little fanfare figure that ties it all together, perhaps meant to be “Bemis’s motif,” but it doesn’t seem to have any psychological meaning; it’s just a compositional device.

Especially at the beginning, Stevens misses the opportunity to give us any particular handle on our sympathies, just offering noncommittal “isn’t narrative splendid” music. (I suppose his intention might have been “a day at the bank” music, which comes to about the same thing.) The long suite of devastation ambiance in the second half is, I think, the most successful passage. And I suppose I respect the way he plays the ultimate irony: neither as sick joke nor as grand tragedy, but as simple pity, clarinet solo over a timpani roll.

The way I misremembered this episode, and maybe the way it is thought of by those who consider it one of the memorable TZ episodes, is simply as the ultimate Alanis Morisettian twist: the guy just wanted, above anything else, to be left alone with a bunch of books, and when he gets his wish, HA! his glasses break and he’s screwed. I didn’t remember the circumstances of his sudden solitude–I really thought it was a supernatural “getting of one’s wish” switcheroo: serves you right for being greedy. But the way the episode really plays out, even though his pre-destruction circumstances are decidedly awful, he still manages to find his little slice of happiness by holing up in the vault for twenty minutes while he has his sandwich. He’s willing to make the best of a very bad lot, and I can’t feel anything but sympathy or even admiration for him. The most put-upon man in the world, he is, and yet he’s still willing to go to the Phillips’ to play cards with that she-devil. The man is a saint!

And despite what the Netflix synopsis says, I don’t think he “rejoices” at all at the destruction. He despairs and pleads, and then, long-suffering and patient creature that he is, tries to make the best of a new terrible situation. At least he’ll have his books, he thinks. It seems a reasonable thing for “the gods” to allow him this slight comfort. But no, once a schlimazel, always a schlimazel, it seems.