directed by Mitchell Leisen

written by Rod Serling

starring David Wayne

with Thomas Gomez and Virginia Christine

Friday, November 6, 1959, 10 PM EST on CBS.

So far on The Twilight Zone, psychosomatic ailments have been presented as weird and terrifying. But in this episode suddenly it’s all vaudevillian. Mr. Bedeker is a clownishly contemptible “type” with “nothing wrong with him” — mental problems being nothing.

Bedeker is served up to the audience as “other people,” who have no interior worthy of sympathy. But the degree of humanity we grant to other people is a consideration that we always eventually turn on ourselves. And vice versa. Here we see the same distrust directed outward that in other more ominous episodes is directed inward. When it’s directed outward it takes on a smug “wry” tone.

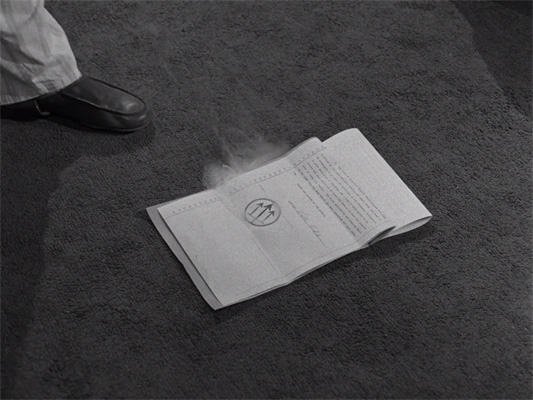

Naturally, Mr. Bedeker gets what’s coming to him; the script trips him with a banana peel and down he goes. Ironic justice — which is to say contemptuous justice — is served, ho ho ho. But it’s just this sort of satisfaction in our outward contempt that keeps the private, inward terrors alive.

The Twilight Zone has two quite distinct varieties of “twists” that we ought to keep differentiated. Bedeker here falls victim to an ironic twist, which really has very little in common with the existential twist of something like Where Is Everybody? or Eye of the Beholder. I am, naturally, far more sympathetic to the latter. Ironic twists, it seems to me, are the residue of cruelty and bad faith.

The classic ironic twist ending is, for the audience, always an uneasy mix of “us”-ness and “them”-ness. Of course “deliciously nasty fates” are things that only befall papier-mâché people, who very decidedly aren’t us, and it’s satisfying to watch them go tumbling. But why do we feel this satisfaction at all? I think it’s because the sardonic, deliberate universe that seizes the poor saps in its pincers is something we tacitly believe in. Dramatic irony is a nervous negotiation with phobia, a whistling in the graveyard. There but for the grace of Rod!

(Setting aside its various infelicities, isn’t this the real meaning of Alanis Morissette’s song? It’s not supposed to be just a catalog of Twilight Zone ironies, but an attempt to evoke the brittle bravado that we assume in the face of such stories — the smirk that tries to mask lonely terror. This is what she means by “a little too ironic,” I think. Yeah I really do think.)

Fear of death is the most natural thing in the world. It’s our biological obligation. Avoiding death is what fear is for. But modern-day culture has placed a tremendous stigma on fear in any form, which means we spend a lot of time concocting ways of convincing ourselves that fear of death is somehow actually childish, or absurd, or too infinite to afford — that it is a mistake.

Serling’s script laboriously tries to demonstrate that too much fear of death makes you a scoundrelly bastard. “You might think you want to live forever,” he proposes, “but that’s just one of those insatiable sociopathic impulses that you must forever suppress. Otherwise look what you’d be like!” None of what happens in the episode makes much sense — what is Bedeker’s internal motivation, at any point? — but we know exactly how to roll along with it because our anxieties are already invested in seeing it reconfirmed that death is better than any alternative.

We’re all well accustomed to stories where eternal life is a booby prize, and quite practiced at being audience to them. In fact the idea that that immortality ain’t what it’s cracked up to be is so completely de rigueur that it’s hard for us to even imagine things working out any other way. If an immortal protagonist lived happily ever after (ever after), that would be a real twist. It never happens.

Once given ultimate assurance of his safety, Bedeker becomes a complete antisocial amoral wild man obsessed with self-harm. It’s an interesting proposition, that the secret desire of a hypochondriac is to court self-destruction; that hypochondria is, perhaps, a fear of one’s own perversity. But we’re not inclined to feel the psychology too deeply, since the conventional anti-fear, anti-immortality imperative explains everything on screen — far better, in fact, than trying to read it at face value.

Because let’s face it, the twist here doesn’t work. Surely our anti-hero would feel that simply sitting back and outliving the society that jailed him — or, for that matter, recklessly attempting a crazy, murderous escape every day — is obviously preferable to conceding ultimate defeat after 30 seconds behind bars. The idea that a “life sentence” is a diamond-hard absolute, impervious even to the powers of hell, is absurd… to anyone, that is, who isn’t already hard on the lookout for something, anything, to serve as the ironic comeuppance demanded by the story logic. But of course everyone in the audience is, and they jump at the chance when they see it: “Sure, that’ll do. Good enough.”

The overt moral is something to do with the insatiability of discontent – “whiners gonna whine,” basically – but it’s a straw moral. The real moral is “don’t rock the boat.” This episode isn’t daring anything or exploring the unknown for even a minute; it’s just smarmily playing along with our anxieties.

It is striking that in a series that aspires to be eerie and unsettling, the two episodes dealing directly with the prospect of death itself (this one and One for the Angels) have been uncharacteristically winking and jocular, with hokey old pantomime versions of “Mr. Death” and “Mr. Devil.” You could see it as a mercenary calculation: “if this isn’t played as an exaggerated clown show it’ll be too grim to watch with the necessary equanimity.” But I don’t buy that. People always take comfort in being leveled with.

There is one moment here that I like. Of his soul, Bedeker asks not whether it will harm him to lose it, but whether he’ll miss it. The devil, pleased at his own wording, reassures him: “You’ll never know it’s gone.” This is how the mind operates. One can’t remember what one isn’t to some degree experiencing. People lose track of their souls this way all the time. No devil necessary.

The acting isn’t bad, given what they have to work with.

The music in the episode corresponds to the contempt: not only is it stock music but stock cartoon music, pieced together out of tiny meaningless snippets. It gives an impression of cagey insincerity, especially taken in immediate contrast to the bewildered earnestness of something like Walking Distance. The music sproings around desperately to convince us that this is all exclamation-point hilarious. That’s a mode that would become particularly prevalent in the 60s — “ha ha we’re zany and wacky and having such a blast aren’t we?” You bet your sweet bippy we are.