The all-Shcherbachov edition. A couple paragraphs on Nikolai Shcherbachov (/ Shcherbachev / Shcherbachyov / Stcherbatcheff) (1853–1922) before we begin.

Apparently Shcherbachov was seen by the other composers in the Belaieff group as something of a dilettante, a talent with undeniable flair but not enough discipline to develop himself. Seems like maybe he was more interested in the musical salon scene than the art itself. He had been introduced to that scene by the critic Vladimir Stasov, who played a major role in shaping all the social/artistic relationships in St. Petersburg. Stasov championed him enthusiastically, apparently going so far as to claim that the top three Russian composers were Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Shcherbachov, and furthermore that nobody since Schumann had composed anything as good as Shcherbachov’s piano suite Zigzags — a claim which unfortunately can’t be evaluated because the piece isn’t yet available anywhere online.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s wife wrote that she couldn’t stand Shcherbachov and didn’t want him at her parties. One of his nicknames was “flagon of perfume” — hard to know whether that refers to literal or figurative perfume.

Belaieff published 28 opuses by Shcherbachov between 1886 and 1893. Then he abruptly disappears from music history. The Grove article on Shcherbachov ends: “Family legend has it that Shcherbachov died in Monte Carlo after gambling away all his money and working for a time as a croupier.”

All the present works were published in 1886 when Shcherbachov was 32 or 33, but since so many of them appear simultaneously, I assume they had been written earlier, over the previous decade, and had remained unpublished. I’m also guessing that the opus numbers only count his published works and tell us nothing about the date or order of composition. (I can’t find indication of a full 14 published opuses prior to the “Op. 15” that marked his Belaieff debut (covered last time), but they probably were put out by lower-profile St. Petersburg publishers and would be unlikely to show up in western libraries — if in fact they’ve survived at all.)

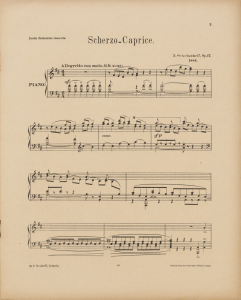

16] Shcherbachov: Scherzo-Caprice, op. 17

Н. В. Щербачев : Скерцо-каприз : для фортепиано : соч. 17.

Scherzo-Caprice : pour Piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 17.

[Scherzo-Caprice : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 17.]

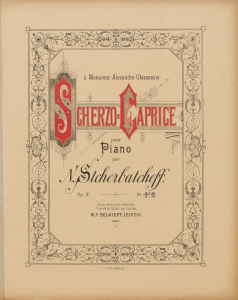

à Monsieur Alexandre Glazounow

• 36 Scherzo-Caprice, op. 17 (1886)

Scanned in color by Harvard (as linked above), and converted into a black-and-white PDF at IMSLP. (There’s also a second copy out there, I think originating from Pianophilia, without any title page.)

This earlier title page comes from a copy currently being offered for sale by Lubrano Music. It has the pre-1898 prices and, obviously, one more printed color than the other; I imagine this is the original form of the design. (It also seems to have been printed on less acidic, probably more expensive paper.)

This is my favorite of today’s pieces, full of genuine surprises and rhythmic wit, and generally bright-eyed and engaging. The affable stop-and-start of the first theme is particularly exciting to me, and I wish he’d gone further with it — but the overall journey of the piece, through various angles of comic sunniness, is still quite satisfying. I think this piece is entirely recital-worthy.

A few sparkling arpeggios definitely put this up in the higher intermediate range — I’m personally not very good at that kind of thing — but there’s nothing actually too difficult here.

To reiterate: nothing by Shcherbachov has ever been recorded. All of the audio in this post is from me and my Casio.

I’ve figured out how to avoid the sound of the keys thudding: I play it into the keyboard’s internal memory and then record its playback (the click at the very beginning is me pressing “play” on the keyboard). This has the added benefit of allowing me to do any tempo tweaking in advance. Most of these pieces were played somewhat slower than you hear them — sometimes MUCH slower — in the interest of playing fewer wrong notes without having to practice.

Note: There are still plenty of wrong notes. Second note: I am just reading my way through these pieces without analyzing or interpreting them or aspiring to any aesthetic value. The service being provided here is purely mechanical: this is the sound of notes that are printed in this score.

That in itself can have aesthetic value, as a spur to the imagination. But you need to bring the right kind of expectations.

17] Shcherbachov: Five Mazurkas, op. 16

Н. В. Щербачев : 5 Мазурок : для фортепиано : соч. 16.

Cinq Mazurkas : pour Piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 16.

[Five Mazurkas : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 16.]

No.1. La bémol majeur

No.2. La bémol mineur

No.3. Si majeur

No.4. Re majeur

No.5. Mi majeur

à Monsieur Alexandre Glazounow

• 37 Cinq mazurkas, op. 16 (1886)

• 357–261 (= the individual pieces from within 37, made available separately around 1891)

Again: scanned in color by Harvard; converted into a smaller pdf version at IMSLP (and again there’s another copy going around out there without the title page). Based on the ads and the prices, it seems to be a printing from right around 1898.

Yes, Op.16 comes after Op.17, because I’m going by the plate numbers and for whatever reason, that’s how it is.

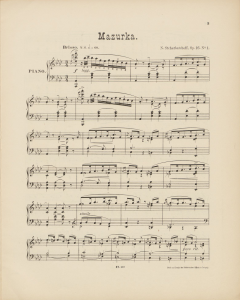

Mazurka No.1. La bémol majeur

In this I can hear exactly the man sketched in the biographical details at the top of the page: flamboyant and a bit frivolous, and a natural talent at it. Some people are talents at flirting, promoting themselves, getting attention. There’s a kind of one-on-one flirtatious charm in these pieces. I can easily imagine a man at the piano who is playing this and winking and smells like a flagon of perfume.

Mazurka No.2. La bémol mineur

As a dilettante composer myself, I find this piece very relatable. A few short phrases are rolled over and over, letting their expressive underlayer gradually sift to the fore. I know how pleasant it can be to meditate on a piece like this as you work it out, and then hope that the same meditation is available to the listener. In this case it is, at least to me. Quiet, gentle choices are the entire drama, but if one’s eyes adjust all the way to the dim light, there’s actually something worthwhile happening from beginning to end.

I like that the standard post-Chopin “melancholy” tone is here complicated — or decomplicated — into something milder and perhaps emotionally subtler.

Mazurka No.3. Si majeur

Obviously these are all in the manner of Chopin, as was so much Russian piano music, but this one in particular just feels like imitation, and rather uncompelling. Actually, this just barely qualifies as an art/recital mazurka — it just seems like a tune for actual dancing. As such it’s not a bad tune. Melody was decidedly a strong suit for these guys.

Mazurka No.4. Re majeur

A more poetic construction, alternating a slow pastoral figure with the demure main theme, which has an appealingly human quality. I especially like the way the theme gains strength as it opens out into the square-yet-graceful refrain, but then rather than reaching a cadence in triumph, floats gently back to where it had been.

I admire pieces that have traditional, symmetrical phrase structures but still manage to give the impression of an underlying flexibility.

Mazurka No.5. Mi majeur

Here I feel like his ideas and intentions outstrip his compositional skill. That’s true of all the pieces to one degree or another, but in the more introspective ones it’s easier for me to find poetic interest in the half-inflated quality (like sleeping on an air mattress through which occasionally you can feel the hard floor). Whereas here in an extrovert piece with a “big introduction,” I can’t help wishing it were fully inflated. The seams feel like seams and I’m not convinced that this adds up to a piece. Nonetheless I do like some of the bits, like the bridge in minor, which knows it wants to flip back to major but isn’t quite sure when to do it.

Op. 16: all in all, this is a pleasant and personable set, if a bit thin and occasionally gawky. The lyrical ones, 2 and 4, seem to me more successful than the others.

18] Shcherbachov: Echos du passé, op. 18

[Н. В. Щербачев : Отголоски : две пьесы : для фортепиано : соч. 18.]

[Echos du passé : deux morceaux : pour piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 18.]

[Echoes of the past : two pieces : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 18.]

No.1. Souvenance

No.2. Rondo joyeux

à Monsieur le Baron Edmond de Beurnonville

• 38 Echos du passé, op. 18 (1886)

• 362–363 (= the individual pieces from within 38, made available separately around 1891)

Harvard owns this one too, but they haven’t scanned it. All we have is a Pianophilia copy (probably scanned from the extensive collection of Pianophilia administrator Malcolm Henbury-Ballan) which lacks the title page.

Le Baron Edmond de Beurnonville, the dedicatee, seems to have been what he sounds like, a rich patron (or at least potential patron).

1. Souvenance. Feuillet d’ Album

[Recollection (Album Leaf)]

I suspect that the title of this opus, “Echoes of the Past,” is meant to indicate that the two pieces share a neoclassical intention (“neoclassicism” wasn’t yet a school in itself, but it was certainly already a popular artistic mode). This is a very pale, candlelit, make-believe classicism, coughing itself to sleep in some 18th-century bedchamber. I don’t want to begrudge this sort of thing its make-believe; the effect may be obvious, but it works. Would be fine as theatrical underscore. I’m not sure I need to listen attentively to it for this whole duration, but maybe I’m not expected to.

If it weren’t for some very minor embellishments in the written-out repeats, this could very easily be laid out on a single sheet of paper, so I believe him when he says it was originally a feuillet d’album. Just the sort of thing to flatter the image of some self-romanticizing salon princesse.

2. Rondo joyeux

[Joyful Rondo]

This is certainly “classical” in a Mendelssohnian sense, but the style seems much more direct, less affected, than the preceding piece. Maybe I’m wrong about “Echoes of the Past” referring to the style. Maybe it’s just a generic 19th-century title. After all, what piece of art couldn’t be called “Echoes of the Past,” in a pinch?

As I said above, the more energetic the music, the harder it is for me to embrace its imbalances and soft spots. The material here is very appealing, but it never gets off the ground the way one wants, and then at the end, after having not quite gone anywhere, an unmerited and disproportionate coda is tacked on. At the top of the coda, a single programmatic indication appears in the score: “Hallali.” This is an old term for a huntsman’s bugle call, suggesting that the whole piece is meant to be a galloping hunt with a glorious conclusion.

Maybe someone else can figure out how to make a case for this piece in performance. All I’ve got to go on is my mechanical sight-reading.

Op. 18: As an opus, this feels a little like two pieces of paper picked up off the composer’s floor at random and stapled together, but that’s fine — a lot of music publishing has always been opportunistic that way. These particular two pieces also both happen to be a tad undercooked. But they do have their charm.

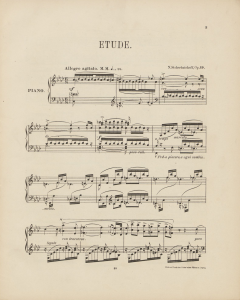

19] Shcherbachov: Grande Etude, op. 19

[Н. В. Щербачев : Отголоски : две пьесы : для фортепиано : соч. 19.]

[Grande Etude : en fa min. : pour piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 19.]

[Grand Etude : in F minor : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 19.]

à Madame Sophie Menter

• 39 Grande etude, op. 19 (1886)

Color scan from Harvard; PDF at IMSLP; an alternate Pianophilia copy is also out there.

This one is a post-1902 printing that’s still in very nice full color, though it’s possible that the earlier printings were even better done.

This seems to be Shcherbachov in a Lisztian mode, aspiring to something a tiny bit more substantial. It’s certainly requires more pianistic technique than anything above (and had to be played very slowly!).

His strengths and weaknesses are both evident. He absolutely has a gift for twists and turns of inspiration, for fantasy — again the word “flirtatious” occurs to me — and an ear for melody. But the implication of all that harmonic drama is that something is being accomplished, and yet in the end I don’t get the impression that anything has been.

The voice of his musical personality is fundamentally extemporaneous; the effort to pass it off as deliberated, well-structured oratory does not flatter it. That just means that a lot of preparation is needed; a performer would need to internalize the piece and be able to act it out as though it were being improvised on the spot — not so different from Chopin. Not having done that kind of work, I don’t really know what’s possible with this piece. I guess I have to reserve judgment. Maybe Sophie Menter knew how to sell it. Certainly it has a surface sweep and glamour, and the structure seems sensible enough, at least on paper.

(That said — Chopin often makes immediate emotional sense to me straight off the page, and feels genuine, in a way that this doesn’t, so I can’t help but be a little skeptical.)

That title page is as attractive as any of the others, in the abstract, but in this case I don’t feel like it resembles the music at all. This is a dark-hued, windswept sort of etude; I can’t hear cherubs and robins no matter how hard I try.

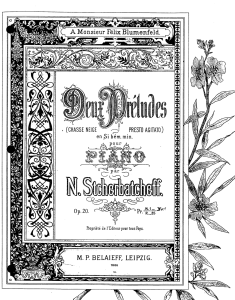

20] Shcherbachov: Two Preludes, op. 20

[Н. В. Щербачев : Две прелюдии : для фортепиано : соч. 20.]

[N. Stcherbatcheff : Zwei Praeludien : für Pianoforte : op. 20]

Deux Préludes : en Si bém. min. : pour Piano : par N. Stcherbatcheff. : Op. 20.

[Two Preludes : in B-flat minor : for piano : by N. Shcherbachov. : Op. 20.]

1. Chasse neige

2. Presto agitato

A Monsieur Félix Blumenfeld.

• 40 Deux préludes, op. 20 (1886)

• 364–365 (= the individual pieces from within 40, made available separately around 1891)

Harvard owns it and just hasn’t digitized it; all we have is a Pianophilia copy in black and white.

Here, apparently grabbing more scraps off his floor, Shcherbachov bizarrely has paired up two underdeveloped fragments that happen to be in the same key as a single opus. Again I’m torn between savoring the eccentricity of it… and calling it out as laziness. It’s as though these could have both been sketches toward the same piece, and then instead of following through on that piece, he just published them as-is, as a very strange set of two preludes.

I may be misinterpreting the title page design, but it looks to me like it’s supposed to depict a book in which flowers are being pressed — an inspired visual for this kind of musical scrapbooking. (The three-hole punches are not original, of course — those are actual holes in the photocopy that was scanned.)

1. Chasse neige. Prélude

[Snow drift(?)]

The title is apparently borrowed from Liszt, but the image is quite different — I think! This is a strangely spiky idea of snow. I see that chasse-neige also means “snow plow,” which I suppose in that era would involve a horse with bells, but that doesn’t seem likely either. I think what we have here is just a very brief little idea, just barely worked out to a just-barely completion, and then given a whimsical and not entirely appropriate title.

A cute idea though. Too bad he couldn’t make a more inspired miniature of it. The first two phrases, which are neither identical nor sufficiently distinct, reveal the erratic craftsmanship at the very outset. This is a piece that clearly indicates the charming piece it intends to be, but fails to actually be it. Then again, maybe it’s just operating on a level of miniaturality below what even I’m accustomed to. Maybe there are bonbon pieces and then there are pieces like this that are only about two M&Ms. It would probably be good for me to be able to eat and enjoy only two M&Ms, without needing more.

(Later: I see that literally, chasse is “chase” or “hunt.” Is it possible that this is in fact a snowy hunt? I could believe it as a rabbit running across a white field.)

2. Presto agitato. Prélude

This seems to me particularly skeletal and sketchy. Does it have a melody? Is the melody absent? Was this actually the accompaniment to a song? Maybe he just forgot.

Then again, why not this? Like the Moonlight Sonata: who needs melody? The more I listen, the more I like its bareness. Three more M&Ms.

Op. 20: Two tiny pressed wildflowers.

In trying to write a few words about these pieces, I have found myself settling into critiquing them as though it’s a problem, for me, that they lack order and discipline. But that’s not how I feel it. I’m actually entirely susceptible to the dynamic of being musically flirted with to no end. There is something very forward and communicative about all these pieces, regardless of their “balance” or lack thereof. He always goes straight for the good stuff. When he runs out of good stuff, he tries to make up a little more, or repeats what he’s got with some twists, and then very soon he recognizes that it’s time to stop, so he does. I appreciate the intentions and inspirations behind all of that; it can all be meaningful to me.

The scope is very small and indoors, but the sounds are attractive, and generally the spirit is too. There’s worthwhile music in here.