Half-Life: Blue Shift

developed by Gearbox Software (Plano, TX)

first published June 12, 2001 by Sierra Studios, for Windows 95/98/Me/2000/NT, $29.95 [original site]

~290 MB (+ 40 MB of Half-Life)

Played to completion in 4 hours, 1/2/15—1/3/15

[Here’s a video of a complete 2-hour playthrough]

[And here’s the 2-minute official trailer]

Yes, here we are back in Half-Life yet again. And there’s quite a bit more Half-Life to come, because I bought it all at the same time.

Here are the notations I made:

It’s a fine line between doing the same old stuff over and over (Take the tram! Turn on the power at the generator! Teleport to the alien world!) because it has become generic (in the sense of forming a genre unto itself), a rewarding ritual like fairy tales with three wishes etc., and doing the same stuff over and over because we are making believe to be surprised each time, like grownups playing peekaboo: “Oh no, where’d you go? Oh, there you are!” I’m not sure which motivation is intended here. Am I supposed to feign not noticing that this is all old hat by now, or am I supposed to be taking my weekly communion at the altar of old hats? (I feel this same uncertainty at musicals all the time.) My experience in Blue Shift was that it was neither fish nor fowl: not a bedtime incantation, and not a novelty either. It was just something happening again.

The design was a tasteful, inoffensive monotony. Even fanfic can run out of enthusiasm eventually.

The original Half-Life has a music to it, like the best Disney rides do. Imagineering is actually a very old art, out of aristocratic entertainments: ballets and tableaux vivants and stuff like that. Not to mention paintings in series, altarpieces and so forth. The arts of theater transposed. Half-Life has that: hall gives way to elevator shaft to control room to fan vent to garage to desert canyon with a confident, inescapably theatrical rhythm. Opposing Force is a little scrappier but still applies itself to that art. Blue Shift has all the same elements in a limp, danceless arrangement.

Or have I just gotten used to the state of the art, in that respect, and become impatient for more and better? I say no. That’s a dangerous supposition, in fact, because it’s what makes designers get off track and fix what ain’t broke. No, the original game still works, isn’t dated. It bears replaying. (If you don’t believe me, just ask Youtube!) Like I said, its writerly attention to dramaturgy was its greatest asset.

The almost purely architectural version of audience manipulation found in computer games is something that even Disneyland doesn’t take to this level. Could you build one in real life, a dramatic experience to be walked through? Haunted houses purport to be that, but the walking itself doesn’t generally have any discovery in it. Over Christmas I was taken to see Longwood Gardens outside Philadelphia, and our walk through the fantastical conservatory structure there, strictly prescribed at high-traffic times by cordons and so forth, was about as computer-game-y an architectural experience as any. All they’d have to do to really bring it to the level of first-person drama (besides adding a story and all that) would be add places where you had to look around until you realized you had to crawl through the ventilation shaft. It’s feasible.

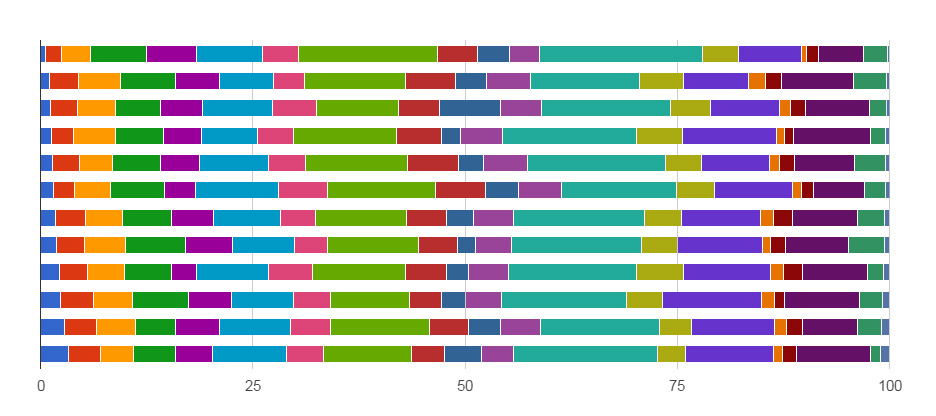

The question of dramaturgy in any interactive medium is interesting; in particular, how do you deliver good pacing when the user’s personality and skill level are going to determine the rate of progress? My gut tells me that drama mostly scales — a good story arc over 10 minutes will also be a good story arc over 10 hours as long as the proportions remain the same. And in games that call on a consistent skill set (or just a consistent user stance toward the material), this tends to work out — a part of the game that takes a fast player 10% of his/her total time will probably take a slow player 10% of his/her total time too. I made a graph to convince myself:

Thanks for the nice colors, Google Docs. The successive regions in each row are the 19 chapters of Half-Life (the game is continuous but every now and then a chapter title appears briefly onscreen) as percentage of playtime for me (top row) and 11 playthroughs I found on youtube, arranged from slow to fast. The very first and last chapters are fixed at 6 and 2 minutes respectively for everyone, so you can imagine the scaling from that.

My takeaway is: yeah, mostly the proportions are the same, so you can see how the dramaturgy could basically hold up. But it also shows the extent of variation, which is not insignificant. And apart from me, these are all self-selected “hey watch me play” Youtube fellows. Other personality types might have different issues and show more drastic variation; you may notice that my row is an outlier here in several respects. In retrospect I think the drama would have been even more satisfying had I been closer to the average pacing seen here. But of course that’s not something a first-time player can aspire to. Most of these other guys are playing through an old favorite for the Nth time. (Though not all of them.)

I’d be interested to see charts like this of, say, the scenes in multiple productions of the same play. Or times for chapters in multiple readers’ experiences of the same novel. I bet you’d see slightly better consistency.

Regarding first-time playing, I do have a criticism of this genre generally: by making ammunition a limited resource that is tracked onscreen and must be replenished after use, the game insists that management of ammo is a satisfying activity for the player to make a part of the fantasy. But while doing this on a second-time playthrough can be based on strategy (e.g. “I know that I won’t get any new grenades for a long time, so I’ll make sure to save this one for use on that sniper who’s coming up two rooms from now”), on the first-time playthrough it can only be based on hunches about the level design (“Well, the game seems to keep giving me plenty of shotgun shells and this area doesn’t seem to be really too focussed on combat, so I probably won’t regret using as many as I need on the two aliens that just showed up.”) This kind of speculation, besides forcing the first-time player to keep guessing about completely boring facts that second-time players will just know (i.e. when’s the next time I’ll be given ammo?), is also bad because it can only be thought about by stepping out of character, since the character would have no grounds for imagining that he’d ever get any more ammo, even after it had miraculously happened 10 times. Even on the game story’s terms, it’s miraculous. In a real scenario, even a comic-book one, there would not be ammunition lying around on shelves in every single storage closet in this lab. It’s absurd. And yet all this ammunition is necessary for the format of the gameplay, which I accept. I understand there’s a problem here. I’m saying it’s not satisfactorily solved, or at least hadn’t been by 1998/2001. And I’m not aware of any new progress on this front. Is there any?

Computer games have always clearly been systemic, rule-based/model-based games with only some thin veneer of story applied to the surface. Half-Life‘s strength was the grace and sensitivity of its handling of that veneer, to the point where it felt like the balance tipped: maybe the story actually comes first! (Behind the scenes, it didn’t. But they disguised that fact better than anyone had before.) But that new illusion was still very precarious. Further artistic exploration was needed to build a really sturdy mode of expression here. As far as I know that exploration is still underway. Blue Shift is so unambitious on that front that it actually backslides a bit. Yes, there are scenes and surprises, but they’re not arranged with much flair. I’m in this for the flair!

In the original game, the scenario was meant to be witty, tongue slightly in cheek. The whole vast sprawling underground government laboratory bunker fantasy was deliberately exaggerated, starting from a comic-book norm and then multiplying it by X. Like the enormousness of the Star Destroyer that goes overhead in the first shot of Star Wars. In 1977 that offered the grinning thrill of overkill. But you know how things always go: along come the sequels, tasked with expanding respectfully on what was once lighthearted, so they have to stop being lighthearted. By the time Mel Brooks did a parody of the same shot 10 years later by making it even longer, he and George Lucas and everyone else had forgotten that that had already been the idea! Nothing like a follow-up to drain the humor out of light fantasy. Just ask Bilbo.

So that’s what happens here. The Black Mesa Incident is now something serious. Even the scientist’s voice is no longer Dr. Frink-ish “funny scientist voice.” It’s just some guy spouting too much sci-fi blahblah like it’s supposed to be really interesting. The charm had been that we easily got the whole scenario without anyone having to say a word, or too many words anyway: well of course they discovered teleportation to another world and well of course they had been experimenting recklessly with it. But in later installments, without any new ideas, all that’s left is to belabor what had once been breezy. Just ask Harry Potter.

Key staff at Gearbox seems to have been essentially the same as last time: Randy Pitchford, Brian Martel, Stephen Bahl, Rob Heironomous, David Mertz. But the scope of the project was different — these levels had been initially designed not as an add-on, but as bonus content for the Sega Dreamcast port of the game. Then when that was canceled, they were repurposed as this product, marketed as though it were something parallel to Opposing Force, even though it’s significantly less than that, and the design team must surely have recognized as much.

The publisher knew to lower the price $10, but $29.95 still seems like a lot. It only took me 4 hours, and I’m slow. It’s never terrible, but it doesn’t really feel like a whole game and it has more infelicities than what came before, places where I got stuck because things weren’t quite as elegant as the standard I had come to expect. Still not bad for the $0.94 I paid.

The fourth item in the “Half Life 1 Anthology” that I bought on 1/1/11 was Team Fortress Classic. This is a pure multiplayer game and I’m scared to play such a thing. In theory I like the idea of multiplayer 3D running-around-and-shooting-each-other games, but I am a shy sort and scared of putting myself out there to be shot at by kids who have been playing these games every day for their whole lives. In my very limited experience playing such games, I am not a natural and tend to make lots of silly mistakes. I would really only enjoy myself paired with similarly unskilled and similarly meek people, and my social anxieties tell me that that will not be easily arranged on a public server. Especially not one for a 16-year-old game that at this point is only played by diehards. So I’m skipping it for now, not out of disinterest but out of fear, to which I am here owning up. I will address future multiplayer games on my list as they arise.

By the way, each of these three Half-Life games so far also had multiplayer options. I didn’t even touch them. I’m okay with that.

If you want to count Team Fortress Classic as a completely wasted purchase, a non-purchase, then I guess each of the THREE games I got in the “Half-Life 1 Anthology” actually cost me $1.24, not $0.94. I’m comfortable with that price, too. So far this has all been basically good stuff.