2000:  (out of print 4/2010)

(out of print 4/2010)

Criterion #69: Testament of Orpheus.

= disc 3 of 3 in Criterion #66, “The Orphic Trilogy.”

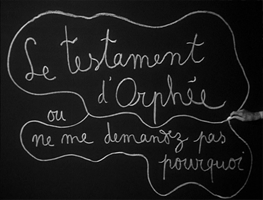

As you can see, the full onscreen title is actually Le testament d’Orphée : ou : ne me demandez pas pourquoi, i.e. “The Testament of Orpheus : or : Don’t Ask Me Why.”

This subtitle appears as a line of dialogue in the movie, immediately after a character informs us that the “idol of celebrity” has six eyes and four mouths: don’t ask me why. So here it means: “Don’t ask me what any of this stuff means. It’s poetry, not symbolism.” Just as at the beginning of Orpheus and Beauty and the Beast, once again, Cocteau is giving the audience unnecessary “instructions for use.” This time he managed to get anxiety into the title itself. Well, the subtitle, anyway. The title proper is just a self-aggrandizing tag: “Orpheus, the Eternal Poet of my prior films? Yes, yes, c’est moi. Now receive this, my last bequest of Poetry to the world.” (Place back of hand on forehead and pose.)

In a nutshell: Portrait of the Artist as an Artist Portraitist, Asleep. Jean Cocteau is onscreen in nearly every shot, playing himself, wandering around inside his own surreal dreamspace, thinking about himself, and interacting with characters from his own prior work, reenacting motifs from the preceding two films. This movie must be the absolute high-water mark for cinematic self-involvement. Bosley Crowther: “It is hard to think of anybody (with the evident exception of Jean Cocteau) who, however egotistical he might be, would have the nerve to make a full-length film about himself. But M. Cocteau has done it.” You’ve done it, Jean! By Jove, he’s done it! He said that he would do it and indeed he did!

Of course, the previous two movies were also all about him. But he wasn’t visible, identified by name, talking about himself and making other characters talk about him. Whereas this is Jean Cocteau’s Playhouse, starring Jean Cocteau playing “Jean Cocteau.” And he even stages that: at one point he and his boyfriend pass another Jean Cocteau walking in the opposite direction. The two Cocteaus peer back at each other suspiciously before the other turns the corner and disappears, leaving our Cocteau dismayed and irritable. “He hates me,” Cocteau tells his companion. “As well he might,” he replies, “He suffered mockery intended for you.”

That excerpt should suffice to indicate the texture of this very strange movie. It is not, like the two before it, a thinly veiled expression of the artist’s hangups: it is a completely unveiled staged catalogue of the artist’s hangups. Having worked my way through miles of Jean Cocteau to get here, absolutely none of those hangups were new to me. But the baldness of the project was, and to my surprise that baldness made it my favorite of the three films. The egomaniacal circularity of it all had a hypnotic effect. The movie has a kind of unary pulsating weirdness that feels like integrity. It’s like a little planetoid, held together exactly by its own gravity.

The integrity derives from the fact that this is how all selfhood operates. My self generates itself, and this self consists of no more and no less than that process of self-generation. Like the sun, which is its own burning. A work of art that operates similarly, as a fixed process of existence, is always going to be of value as a meditative object. No matter how vain and angsty and petty its materials. I found this other person’s dream very easy to relate to, much moreso than the preceding films with their awkward modicum of “modesty” and “objectivity.” In those films I saw various kinds of evasion. Here I saw a person’s mind as its own existential sun, with no escape. This I can believe.

I don’t know if Manny Farber’s dichotomy of “white elephant art” vs. “termite art” is so great or necessary, but it has force and has stuck around in my head. (Summary: White elephant art = top-down = calculated to fulfill imposed forms, satisfy inherited ideas of quality and dignity = mostly worthless; termite art = bottom-up = form is generated only by the inexorable “termite-like” processes of the artist’s work = valuable.) Farber’s idea seems to be that “form” is inherently suspect, and that the real artistic goods will always be ragged-edged, like a fungal growth. But this kind of self-sustaining/self-devouring film seems to me to be the ultimate in termite art, and yet also satisfyingly well-formed: a complete organic process that happens to take the shape of a perfect sphere because it is organized around a single obsessive center: “I”.

Other planetoidal works from my recent experience, which came to mind while watching: Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, also about the dreamlife of the real author as he writes the very work we are reading (gay, French); Roussel’s Locus Solus, also about surreal dream-images hashed out with ostensible analytical rigor that only becomes more of the same dream (gay, French); Proust’s Big Book of Proust, also about the inner poetry of the “I” that generates the work we are reading (gay, French); Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which is of course all dreamy-analysis and analytic-dreaminess, and which also circularly contains dream-descriptions of itself and its author and its writing and reading processes and its own circularity (not gay and not French, but heavily influenced by French writers.)

Also — rather less pertinently — the scenario at the beginning of the movie, where Cocteau is a time-traveling ghost who encounters a professor at different phases of his life, surprised me by calling to mind the horror story “The Professor’s Teddy Bear” by Theodore Sturgeon (warning: extremely creepy). Surely Cocteau was not a reader of Weird Tales and the plot similarities are a mere coincidence. Nonetheless it does point up a sort of pulpy Twilight Zone thread in Cocteau’s work — think of the car radio that receives broadcasts from the underworld, in Orphée — which throughout this trilogy has appealed to me as the one unabashedly enthusiastic element, free of self-regard. I don’t know from where exactly this sort of off-kilter sci-fi stuff got into Cocteau’s head, but its ego-function is simply as intriguing fodder for Cocteau-as-spectator, lover of fantasy, and in this role he and I overlap quite genuinely.

I endorse Testament of Orpheus, with full knowledge that it is not for everyone and in fact maybe not for anyone. Not even for Jean himself. It simply is. It is a disembodied self-indulgence, a dream about dreams, but without any dreamers. That feels like a real kind of art, to me. One with no inroads and no function. If you can dig it, this is a fun one.

There are a passel of celebrities in it for no good reason. Like, Pablo Picasso, for a second. He is in a tableau recreating the society onlookers from Blood of a Poet. His onlooking is fairly hammy. Elsewhere, Brigitte Bardot is in there (as well as Roger Vadim; everyone stay tuned for Criterion #77!), as is Jean-Pierre Léaud (everyone remember Criterion #5 and stay tuned for Criterion #185!). And of course Yul Brynner in the role he was born to play: Athena’s receptionist or something. And others.

At the end Cocteau says out loud (I paraphrase): “You may have noticed some celebrities along the way. They were not included because they are celebrities, but because they suit their roles, and because they are my friends.” Or to paraphrase more loosely: “Follow me on Instagram #SaintTropez4eva OMG I’m such a dork ;).”

Cocteau has found a really fantastic location, a bauxite quarry in Provence, and he uses it to the fullest. It already brings with it all the mytho-symbolist suggestive atmosphere he needs. Some of the most compelling sequences are the ones where he lets the location be the show and just wanders through it.

My criticism that Cocteau does not know how to handle pacing has finally been put to rest. By the age of 70 he had either figured it out or let his collaborators guide him a bit more. The film has flow and a sense of mystery in the cutting. That counts for so very much, in this game of the unknown and the unknowable. That alone would make it my favorite of the three.

So now that it’s over, what was “The Orphic Trilogy”?

Well, I am hard pressed to find any evidence that it was so named or considered by Cocteau; seems like he thought of all his works as thematically and spiritually interrelated, not just these three films. The first reference to an “Orpheus trilogy” that I find in Google Books is in a 1975 book of film theory, in which the modes of reportage and creative interpretation are intermingled; the reference to a trilogy can easily be read as being that author’s own observation and coinage. There are a couple more such references in the following two decades. Then after Criterion released this box set, suddenly the tone changes and “The Orphic Trilogy” is widely referred to as a thing. What I’m saying is that it might not be a thing.

That said, the links among the three films are quite explicit, and this third one is so overt about being a riff on a riff that it actually begins by replaying the last few moments of Orpheus as a refresher, or as a dovetail joint. But when one thinks of a “trilogy” one tends to think of something like an altarpiece in three panels or a story told in three chunks, or a sequence of three adventures in the same world. These films are more like three times that an artist did the same thing, with cumulative knowledge of his prior efforts. But they fit into a body of work that (I am led to understand) increasingly consisted of doing the same stuff over and over in varied forms.

I don’t hold the boxset or its title against Criterion; it makes good sense. I just think that as far as my finding something to say about the mysterious spine #66, there is no such overview for me to take. The films fit into one another like nesting dolls and leave no synthesis left for the viewer. This last one has already eaten up and incorporated any kind of perspective I could try to have at this point. The anxiety of the artist will always get there first!

This movie sets out to be a kind of ultimate arthouse movie and succeeds. Watching it is like scuba diving through endless poetical seaweed; not to pick it or identify it, just for the sweet sleepy creepy ambiance. I made a tongue-in-cheek movie like this when I was in high school, where (if I recall correctly) an everyman is questing through a dreamscape after an apple, but menaced by a paperclip. I made it because I thought such things were funny, but a special mesmerizing kind of funny that some pretentious people considered serious — which was what made it so funny! Now I see that what I was doing was not parody after all, but the thing itself. Daring to be absurd — daring to seem pretentious! — is the same serious joke, the same risk and the same reward, at any age. There are parts of this movie that made me chuckle because they were so hilariously damned poetical. But I was always simultaneously able to be on the flip side of that chuckle, underwater.

Like I said for Blood of a Poet: dream-art is a good thing, and we should love what we have of it as best we can.

Villa Santo Sospir is on here as a bonus film, but I’ve already seen it because the new issue of the preceding disc took it over after the boxset went out of print; remember how that worked?

The only other bonus feature is an essay by Cocteau, which is again, as usual, both sympathetic and anxiously overarticulate about how none of these things can be articulated. “Everything that can be explained or demonstrated is vulgar,” he says (actual quote this time!), while of course in the process of explaining and demonstrating. I know what that’s like. Where else can that energy go? One must simply wait it out, and make speeches with it while one waits.

Here is a passage I would like to keep, so I copy it out:

This time, in my film, I was careful to make the special effects serve the internal, not the external, development of the film. They should help me to make this line of development as supple as the thought processes of “un homme qui gamberge” — to use a splendid term not found in our dictionary.

“Gamberger” means to let the mind follow its own, uncontrolled course; and, while it is different from dreaming, daydreaming, or reverie, allowing our most intimate notions (those most tightly imprisoned within us) to escape and flee unseen past the guards. Everything else is just “thesis” or “flair”: I am repelled by both.

A thesis forces us to “buckle the wheel,” to twist it so that it will obediently follow an artificial line, while flair incites us for no valid reason to accelerate, slow down, or reverse, and although it is very tempting to use these devices, the effect of surprise only carries weight when they are integrated into the task and remain unobtrusive.

Good advice here for those seeking peace of mind, and I like having a suitably new word for it.

This movie has the most elaborate music credit of any so far:

Musique enregistrée

sous la direction de

Jacques MétéhenIndicatif musical et Trompettes

de

Georges AuricStructures sonores

J. Lasry et F.B. BaschetPiano-jazz

Martial Solal

The majority of the underscore is classical. We hear one movement by Handel three times (Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 No. 4 (HWV 322): I. Larghetto affettuoso) and if I weren’t so set on picking original music, that would be our “theme from Testament of Orpheus” for sure. Under the title we hear, appropriately enough, Gluck: Orfeo ed Eurydice — Minuet. During the scene of building a flower in reverse motion, we hear Bach: Orchestral Suite No. 2 BWV 1067 — 6. Menuet, 7. Badinerie And late in the movie there’s a theme from Tristan und Isolde but I can’t find it right now on Spotify so forget that. This stuff all goes uncredited and unidentified so I enjoyed identifying it, especially the Handel which I didn’t know before. That’s the only reason for all these Spotify links. Anyway, I assume that stuff was all conducted and maybe arranged by Jacques Météhen.

As for the Lasry/Baschet “structures sonores,” these are used for eerie sound effects in a few places, mostly corresponding to the appearance and disappearance of the hibiscus bloom that Cocteau carries around throughout the film (representing his poetry/soul, of course). (I had heard of Baschet’s musical sculptures before because of my interest in film scores, but not this one — they are a footnote in the pre-Jaws work of John Williams.)

The “piano-jazz” by Martial Solal makes just two brief appearances as the sound of “young people,” one of Cocteau’s fixations.

So that leaves us with Georges Auric again, who we see has not actually composed much original music at all this time: just an “Indicatif musical” and “Trompettes.” The trumpets are some unremarkable fanfaric stuff when Cocteau finally reaches the temple of Athena. (spoiler: She turns away coldly, then kills him when his back is turned. But then he returns to life and continues wandering the earth. She is essentially the same character as Lee Miller in Blood of a Poet.)

So our selection is going to be Auric’s indicatif musical, which I believe refers to the music played at the very beginning of the movie during the footage from Orpheus: a cue, newly recorded and maybe rearranged, from the Blood of a Poet score. This is apparently meant to serve as The Poet’s “theme music,” though it’s sort of a slithery little cue and, as is usual for Cocteau, an odd choice, dramatically. But in any case, it links the trilogy together (for those of you who have watched Blood of a Poet recently enough to recognize this snippet, that is) and is the only original music in this score that’s in the clear. So here it is: Prologue.

That’s enough. Good night, Jean Cocteau. It’s been real. No, wait, not real. It’s been not real.

As I kid I had a book consisting of licensing and aptitude tests from a variety of professions: florist, bartender, interior decorator, etc. (More fun than it sounds!) One of them was from, I assume, a survey course on psychology. I can still remember a quiz question elaborately describing a patient, Peter, and his various narcissistic tendencies, and being shocked by the correct answer: “Peter is likely a homosexual.” It seems today like a crude Freud-era equivalence. But maybe they were on to something… at least when it comes to the sorts of homosexuals who were liable to be out (kind of) in Freud’s day.